Alice Golay (alias Rivaz) and the ILO / Ivan M.C.S. Elsmark

Category : Centenary - Testimonials

Alice Rivaz (1901-1998) is well known as an important literary personality, not only in her native French-speaking Switzerland but also among French language readers – and from translations into German and ltalian – throughout continental Europe. Over the years she has been awarded several prizes, among which the Schiller Prize (1942 and 1969), the City of Geneva Prize (1975) and the Grand Prix Ramuz (1980). It is however not the intention here to deal with literary achievements as such, but to try to trace her life in the context of the ILO. In writing this article I have read with pleasure most of her books, and can only recommend my former colleagues to do the same.

Who was Alice Golay?

Behind the pen-name Rivaz is hidden that of an ILO official, Alice Golay, who for more than 25 years served in such positions as shorthand-typist, documentalist and research assistant. At a time when career prospects for junior staff were limited, and even less for a woman, she had to renounce her inclinations in order to earn her daily bread as an office worker. Few of her superiors or colleagues took notice of her talent and personality and the files1 contain only scattered information.

Although she wrote thousands of abstracts and drafted reports and articles, nowhere do we find her name in an ILO publication. Her life’s work was to be in the world of letters.

The daughter of a “red” socialist.

Alice Golay was born in Rovray (Vaud) on 14 August 1901 where her father at the time was a school teacher. In l9l0 the family moved to Lausanne where Paul Golay devoted himself entirely to

journalistic and political activities in the Partie ouvrière socialiste vaudois. “My father was a black beard of thick velvet, a pipe behind a large newspaper,” and she herself was referred to as “the chief socialist’s small girl,” as she recalls in her book I’Alphabet du Matin (the Morning Alphabet). A forceful orator and pamphleteer, he was a member of the Grand Conseil, the Conseil Communal de Lausanne and, from 1925, of the Conseil Natioral.

Music early became an important part of Alice’s life and in 1920 she graduated from the Conservatoire de Lausanne as a piano teacher. To her disappointment her small hands did not permit her to accede to virtuoso classes, and the theme of failure and being unable to fulfil an artistic ambition later appears in several of her books. Thus, seeing neither a future as a piano teacher nor being willing to seek material security in marriage she took, in 1921, an accelerated steno and typing course to prepare for secretarial work.

It was not easy for Alice Golay to find an office job due to the political involvement of her father. His advanced views, “ses-Idées” as his daughter said, “threw him into a difficult social and political struggle” … “at a time when socialism was the scarecrow of decent people, in a country where the lowest form of middle-class and religious conformism reigned”.

How Alicc Golay came to the ILO.

Paul Golay was a man of action. On the suggestion of Emil Ryser, a friend and ILO official, he wrote in October 1921 to the ILO Director Albert Thomas to obtain employment for his daughter, emphasising her good general educational level and knowledge of English. In a sympathetic reply, Albert Thomas suggested that Alice should enter a competition for vacancies as shorthand-typist. Thus, on 25 March 1922 she sat for a two-hour examination, but, unprepared as she was, she failed, placing number 36 out of 44 candidates, ostensibly due to insufficient familiarity with ILO subjects.

Undaunted, Paul Golay wrote again, frankly exposing his daughter’s dilemma. He pointed out that in spite of her qualifications her career was “severely handicapped as the daughter of a militant socialist. Her father’s political life fetters and paralyses her”, she is rejected by the bourgeoisie and even prevented from taking up studies as a teacher. And he continued: “Certainly, it would be ridiculous to expect the ILO to provide asylum for those who are handicapped because of their political views, or those of their family. But I wonder if it would be totally incorrect, without requestirig favours, not to take these circumstances into account”.

Not before 12 April the following year could Alice Golay participate in a new competition but this time she was well prepared and passed as number one! If she then expected to be employed, she was to be disappointed. Although recruited from 24 May to 10 Iuly 1924 for the 6th Session of the International Labour Conference, no opening was offered to her. Was it simply bureaucratic inertia? Paul Golay again turned to Albert Thomas who decided that the first relevant vacancy should be offered to his daughter. Hence, in March 1925 she was again proposed for the Conference, and subsequently engaged by the Office.

In the Typing Pool

Alice Golay entered the ILO on 15 June 1925 as a shorthand-typist (class B-monolingual) in the Typing, Multigraph and Roneo Branch. It must have been somewhat of a cultural shock for the young pianist to enter the busy offices of the typing pool under the strict command of its head, Geneviève Laverrière2, whose image we recognize as the authoritarian and beautiful Mrs. Fontanier in the novels Comme le Sable and Le Creux de la Vague. In these novels she remembers the Pool as a unit with many young women of different nationalities working in a “very feminine atmosphere which prevailed in Mrs. Fontanier’s branch”, each having “chosen this new and attractive career of an international official, … but at the same time started an existence different from her own and that of her surroundings” (Le Creux de la Vague). As she later described the dilemma in Comptez vos Jours, “separated because I am not married, because I have no children” … ” separated from my fellow-countrymen because I earn my living not among them but among foreigners,” … ” separated from myself because I am torn away from what I was, without being the one I am to be when I have shed the slough”.

In her books she recalls the view approaching the ILO lakeside building: “A large park with old trees, a gray frontage hidden behind the branches. But when following the small footpath covered with dead leaves, … one arrives at a parking lot, and what immediately meets the eyes is not a pretty bourgeois residence, but large barracks as ugly as a factory”.

In her diary and novels she describes the lake, the park “which surrounded the immense building … a marvel of softness and mystery”, the marbled entrance hall, the long corridors, the “mysterious” typing pool, the offices with in-trays full of documents and journals, the walls “decorated” with files, the desks covered with books and papers, the busy officials with their briefcases, the talks on professional and sentimental issues, the homes with the photograph of Albert Thomas! She observed it all and wove it into her novels as a backdrop to the essential human sentiments of love, hope, disappointment, egoism, and the fate of women in an often hostile society.

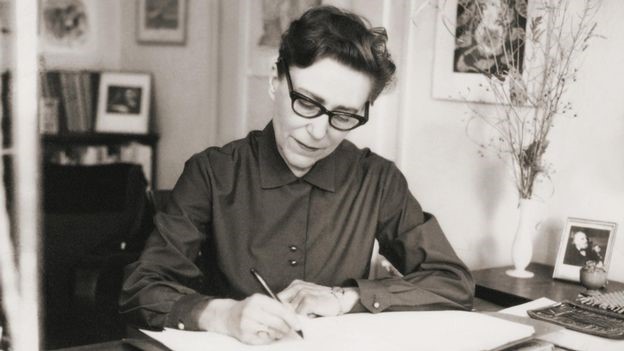

Alice Golay

At first she rented a room at quai des Bergues but in 1932 she settled into a new small flat (two rooms and a kitchen) on 5 rue Théodor Weber, which was to remain her home until 1992. For Alice Golay, Geneva appeared as “la Babylone helvétique“, so different from the world she had previously known. Like Hélène in her book Le Creux de la Vague, “year by year, the new life had taken a larger and larger part, while the old one less and less”. Thus while at first her chief Mrs. Laverrière regretted “a certain tendency to chattering and concealed inactivity during working hours”, she quickly seems to have adapted herself to the office routine and already in May 1926 she won an internal competition and was promoted to clerk-1st class.

The toils of a documentalist

It was a new challenge for Alice Golay when, in June 1926, she was transferred to the Documents Service of the General Information Section. In the job of dépouilleuse she spent the next thirteen years, a period of her life on which she frequently drew in her novels.

Her duties were to analyse and prepare abstracts from incoming French language periodicals and documents. In this work her good analytical and drafting skills came to great use, and she was noted for her “well chosen selection of information” and “the intelligent and careful drafting of abstracts”, unfortunately “blemished with typing and spelling errors”.

The workload was extremely heavy and her chief, Miss Marie Schappler, was highly demanding and kept detailed output statistics, as can still be witnessed from the files. “Exigent of her staff and of herself … strenuous in her work and devoted to the service” (as stated in a report), she lived mainly for the Office and expected her collaborators to do the same. Alice Golay suffered under the burden and in Jette ton Pain she describes how she “at the Office was sinking under an excessive workload, obliged each day to produce 35 abstracts from newspapers and periodicals, not counting French parliamentary debates”, which figured among her daily tasks, frequently obliging her to take the papers home and work till late into the night to finish the work. Her endeavours were appreciated and in 1939 her chief complimented her as “one of the best dépouilleuse” in the unit.

First literary steps

ln Le Creux de la Vague the heroine makes the following remarks about her career: “I have really made a good choice, she suddenly thought with a pang, shutting the door of her car, as if she had waited twelve years to pose this question and was starting to dream of a life which could have been hers if she had wanted”. The choice in life – and to have the courage to make it – is a theme which frequently occurs in her works. ln Comptez vos Jours she poses the question of the role of women in an age where the offices “slowly develop a new form of female servitude and greatness?”.

Feminist, pacifist and socialist, Alice Golay was very much aware of the social and political turmoils of her time. Geneva had been hit by a serious economic crisis and unrest which in 1932 culminated in a large demonstration suppressed by military force. Against this background she made a first attempt in 1935 to write a novel but the manuscript was later destroyed. A new impetus to her literary interest was the creation in 1936 of the book-club La Guilde du Livre. On the suggestion of its director, Albert Mermoud, she wrote an article about the Guilde, and during her holidays at Côte des Maures in July the following year she started writing the first fragments of Nuages dans la Main (Clouds in your Hand), which was to be published in 1940.

Deceived

Somewhat naively Alice Golay got herself involved in a sordid affair which could have had serious consequences for her. A colleague, Heidi Flubacher-Stöcklin, had befriended a certain Yves Le Gallou (alias Marcel Dupan or René Landais) whom she assisted in selling an expensive property in Barcelona, ostensibly for the benefit of his infant son. During Le Gallou’s stay in Geneva, Alice Golay had permitted him to spend some nights at her loft, and to keep a suitcase there, believing that he was a conscientious objector without resources. It later emerged that he was a known imposter, swindler and thief, and had been using the suitcase for hiding stolen goods. After his arrest, Alice Golay was called as a witness in the case, which was widely reported in the Geneva papers. As a result she was suspended from her functions as from 27 December 1939, pending a disciplinary inquiry. When the court laid no charges against her, she voluntarily resigned on 3l January 1940 under the general scheme for wartime staff reduction receiving from the Pension Fund some 20,000 Frs.

A new life

In her diary (Carnets 1939-1982) she wrote: “My last day at the Office. I spent it putting order in my drawers and cupboards. … I have worked fourteen years and eight months behind these walls, fed up of spending my life shut up from morning to night just to earn it. But today I feel somewhat heartbroken at the idea of leaving. This table, this office, these two big windows opening onto the beautiful trees, the changing sky with the passing clouds, all that, during fourteen years and eight months I have looked at while working. An office which, little by little, becomes a kind of second home where one lives all day. In particular an office such as ours, as Liliane said to me yesterday, where we have experienced many things other than just earning a living … Yes, many other things, our friendship, our love affairs. This is where, year by-year, our hearts have grown long and strong roots”.

Like many who abruptly stop working, the departure from the daily routine left an unexpected void. She confessed in her diary: “Yesterday was the first day of freedom. How often have I not wished for this freedom which would permit me to write! But my reaction was unexpected. I neither felt like writing, nor painting, nor playing music. For the first time I would have preferred to work at the office”. … “I had not realised to what extent I needed the others, the presence of my friends and c-workers. This impetus, this excitement, this internal energy which I thought was my own, it was they who gave it to me. When I meet someone, I start living again. I see and listen again. For that reason I was able to write these three pages, because I communicate with the others”.

Wartime and literary pursuits

The war broke out in Europe; she was now unemployed, but for her it was “the very best gift: time to write”.

In July 1940 she had completed Nuages dans la Main which was published by La Guilde du Livre in December that year on the recommendation of the well-known author C. F. Ramuz. For her parents, her literary pursuits came as a surprise, and their reactions were mixed. Paul Golay wrote her a letter listing in detail what he considered the “faults” in the work and recommended that she start all over again; her mother appealed for suppression of certain pages which she thought “scandalous”.

To protect her family and patronym, Alice Golay chose the pen-name Alice Rivaz (from a village not far from her birthplace). Later in her book Ce Nom qui n’est qas le Mien (The Name which is not my own) she reflects on this dual personality which she had assumed, navigating between an Homerian Scylla and Charbydis, with a wish to hide in privacy while stepping forward to be known and recognised.

In 1942 René Juillard obtained the publishing rights for France. Some linguistic changes were undertaken as well as reference to Hitler and the war because of the occupation. In the preface the academician Edmond Jaloux criticised certain “helvétismes et négligences de style”, which actually had been corrected in the new edition and he attacked the international organizations, and in particular the ILO. This led to a conflict with Alice Golay, who only discovered the text in proofs; on her insistence the reference to the ILO was omitted. Like her father, she had courage and could stand firm.

In the following years she wrote several novels under her pen-name Alice Rivaz, of which Comme le Sable was published in 1946 and Paix des ruches in 1947, an anthology of French poetry 1942), while together with her former colleague, Suzanne Fontana she translated the novel by John Brophy: Immortal Sergeant. Under her own name she also contributed articles to several journals, mainly on feminist and social issues. To supplement her income she held various temporary jobs, in particular with the Anglo-American Press Bureau, which later provided background to her novel La Paix des Ruches from 1947.

Hard times at the ILO

With the end of the war the Press Bureau closed in August 1945 and she found herself without employment. Hence, on 5 April 1946, she applied to the ILO for reintegration, but only after the return of the “Working Centre” to Geneva and the intervention of Charles Schürch, the Swiss trade unionist, was she re-engaged from November 1948, not as a documentalist but as a registry clerk! A surprising decision considering her past career and literary achievements, but there seems to have been no other vacancies and she badly needed a job.

The three years that followed probably the most unsatisfactory physically taxing for her. Assigned to indexing of incoming correspondence, she had neither the experience nor the physical strength to deal with the tasks imposed on her. The staff worked under the watchful eye of the Registrar, Gustave Dubourg, and his assistant, Mrs. Marthe Barambon who from a glass window in the neighbouring office followed the progress. There is no doubt of the purely manual requirements of the job; as Dubourg noted: “in addition to the professional qualifications of the candidates, physical strength is of importance, as entries in the various registers obliges the person to remain standing up for long hours”.

Her literary activities came to a halt and in her diary she complained: “Seven months of silence and indescribable moral sufferings in a state of rigidity, in spite of my change of life and return to the ILO and the obligation to concentrate on a new job which they say is temporary, but which is completely against all my likings and does not correspond to my professional knowledge, a real manual labour carried out standing, consisting in moving and replacing index cards in draws which are very difficult to open and close. … I discover now the fatigue in the body, the muscles, the legs, the back the neck only creating one profound need: to go to bed once the drudgery of the day is finished and wipe it out in sleep”.

Her report for 1949 is critical of her insufficient knowledge of Registry work and procedures while acknowledging her good will and interest in ILO activities. As a result the Promotion Board prolonged her probation period and withheld the annual increment while considering “that Miss Golay was probably not suited for the duties required of her in the Registry and further recommends that if and when a vacancy occurs in another Section or Service, Miss Golay should be given an opportunity of a transfer”.

The next year the report was more favourable and her appointment was confirmed. Things also started to look brighter. She was temporarily promoted to AMD (Assistant Member of Division, a junior professional post) and on 1st September 1951 transferred to the Manpower Division.

Family affairs

Unfortunately this turn for the better was accompanied by personal worries. Her father Paul Golay had died in June 1951. Together with her mother she rapidly compiled a volume of his political writings (a selection from his some 7000 articles) which was published the same year as Terre de Justice. Both father and daughter were talented writers, but Paul Golay had no literary ambition, his writing was a tool in a struggle for his convictions. Her mother, Marie Golay, then moved to Geneva to stay with her daughter in her small flat. Life together proved a serious strain in spite of their loving relationship. For Alice Golay, it was a new obstacle in finding time to write. She later drew on this experience in chapter IX of Comptez vos Jours, and in Jette ton pain she describes with feeling and honesty the tension between the two, slightly disguised as Mme Grace and her daughter Christine.

A new beginning

At the ILO Alice Golay had at last returned to a post where her abilities and experience were appreciated. After four months in the Vocational Training Section she won a competition and was appointed as research assistant in the Employment Section from 1st January 1952. A plan to send her to Belgium to acquire experience of employment service had to be abandoned because of her family situation. In her new job she found a challenging, although often exhausting, activity and, more important, a friendly and more human relationship among the staff and with her superior.

A nice custom at the time was for the Director to congratulate members of staff on promotion. Alice Golay received such a letter from David Morse on 7th January 1952 to which she replied on 11th January, thanking him for the confidence shown in her and assuring that she would do her best to accomplish her new tasks in the best interests of the Office, thus participating in achieving the common goal of social justice.

Her direct chief was Donald L. Snyder who thought her “conscientious and hardworking, [with] good judgement and reliability”, … “co-operative and intelligent, and a valuable and effective member of the Section”. Her duties during the next eight years spanned widely-differing areas dealing with employment situation and labour market issues through the employment services, questions relating to older workers and women, preparation of some 600 abstracts annually, assisting in research and occasional translation of texts. Not necessarily an exciting occupation for a person of her sensitivity.

Although her name does not figure as the author (most staff-work appeared anonymously) she wrote notes for Industry and Labour and the International Labour Review (two articles, June 1954 and July 1955, on the employment of older workers and on older women), a report for the Textiles Committee (1958), a chapter in the report The Age of retirement for the European Regional Conference (1955) and a report on employment of older women workers prepared for the UN Committee on the Status of Women (9th Session, March 1955). On the latter she revealed in her diary that she “knew nothing about the subject” and “to have to fabricate such a study in six weeks all on her own was madness.” – But still she did it!

She was longing for time for her literary work. In her diary she counts the time spent on her daily activities: “At the Office: 8 hours; working at home for the Office: 2 hours minimum; four journeys by tram of ½ an hour each: 2 hours; three meals: 2 ½ hours. Total: 14 hours”. – And she adds: “Under these conditions, how can I dream of writing even notes in this diary?”

Alice Golay had a good relationship with her colleagues, and one them, Antoinette Béguin, still remembers her as “a charming person, kind-hearted, soft-spoken and friendly. She took an interest in people, but was never intruding or indiscreet. She had a sense of humour, but with kindness and never at other people’s expense”. Office life gave her inspiration but as she explains, those “who surround you in daily life, with whom you work at the office, those whom, in your thoughts, you can’t avoid modifying, deforming, partially erasing, and at the same time adding something to them, exaggerating certain of their gestures, giving them qualities and faults which are not necessarily theirs, behaviours in which you encase them – thus having the impression of lifting them above themselves, or on the contrary debasing them, or indeed reincarnating them in a completely new person to become a character in a novel”.

Free end recognized

On 4 May 1958 Alice Golay noted in her diary: “Mother has died in the course of a long sleep without agony …”. Her grief at the loss was mixed with a feeling of relief, to be free again to take charge of her own life. A second event was the offer of a contract by the Foundation Pro Helvetia which hastened her decision to devote all her time to writing. “Small fact with great consequences because it incites me to resign from the ILO earlier than I thought I could” … “Hope to realize at last what I dreamt about for such a long time”, as her diary records. Thus on 12 February 1959 she gave notice with effect on 15 August; she was then 58 years old and free again to pursue her literary interest, as well as music and painting.

It is with a certain sadness that one reads the entry in her diary: “Today, 31 July 1959, my last day at the ILO. … If I add the years I worked at that organisation, between the two wars and after the last, it comes to twenty-five years and some months, all my best years lost, except for the time during the war when I for the first time had leisure to write.

In the years to follow she published i.a.: Sans Alcool (1961), Comptez vos Jours (1966), Creux de la Vague (1967), L’Alphabet du Matin (1968), De Mémoire et d’Oubli (1973), Jette ton Pain (1979), Ce Nom qui n’est pas le Mien (1980), Trace de Vie, Carnets 1919-1982 (1983) and Jean-Georges Lossier, Poesie et Vie intérieure (1986). Many of her books are currently being reissued by the publishers L’Air, so readers again can enjoy her works. Her writings have been honoured by many prestigious literary prizes and a memorial tablet has been placed on the building at 5 rue Théodor Weber where she lived from 1932 until 1992. Her last years were spent at the old people’s home “Mimosas” where she died on 27 February 1998.

_____________________________

1 In particular the files P. 1648, P 6/8 pt..II, P6/14/1 and PD 6/1/20.

2..She has « su maintenir une exacte discipline au sein d’un personnel nombreux, hétérogène, qui travaille dans des conditions sensiblement plus pénibles que celles qui prévalent dans les autres services”. (Quoted from the 1935 report.)

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO