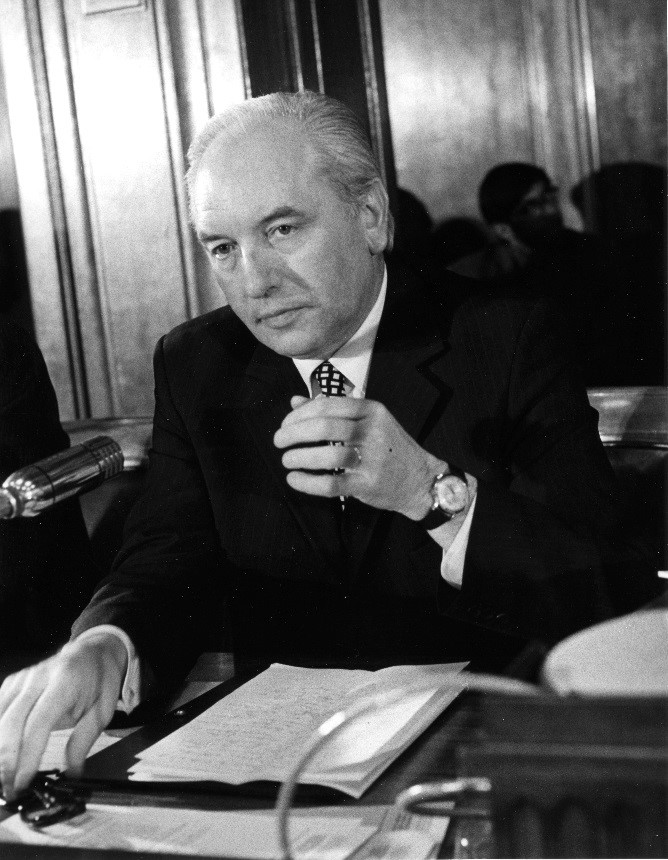

The ILO, Freedom and Democracy / Francis Blanchard, Director-General, 1974-1989

Category : Centenary - Testimonials

I was three years old in 1919 when at the family table I first heard speak of Albert Thomas and the International Labour Organization.

Almost every Sunday my father invited some of his veteran friends to lunch, and among them was Jean Toulout, President of the “Fédération des artistes comédiens” and an intimate friend of Albert Thomas. My father, a sergeant-major in an artillery unit, had been seriously wounded during the battles of the First World War. After being treated in a military hospital and after a period of convalescence my father was assigned, thanks to Jean Toulout, to an obscure position in the Cabinet of Albert Thomas.

Around the table, conversation centred on the hardly-won victory over imperial Germany, and on Albert Thomas to whom had been entrusted in 1917 the weighty burden of the Armaments Ministry on which the uncertain outcome of a conflict which had been going on since 2 August 1914 depended. The participants engaged in a friendly quarrel over whether the President of the Council of Ministers or Albert Thomas was the true architect of the victory. My father considered Albert Thomas to be a demiurge, i.e. a person with the gift of extraordinary creative powers. They were all agreed as to his genius. They differed over his appearance. Some saw him as short in stature and stocky, others as rather corpulent and always dressed in black,.That being said, I leave it to the ladies who are gracing this meal to decide. These lunches invariably finished with patriotic and drinking songs.

Albert Thomas was the son of a baker at Champigny in the Paris area. My grandfather was a baker in Burgundy at Tournus, a Roman town nestled alongside the Saône. You will understand from this evocation of a very distant past that I claim kinship with Albert Thomas. But there is more. When I went to university my professor of labour law was Pierre Waline at the School of Political Science. Pierre Waline spoke to us of the first steps of the ILO under the committed directorship of Albert Thomas. As a young official I worked with Adrien Tixier, former assistant-director of the ILO under Albert Thomas and Minister of the Interior under General de Gaulle; at his side was Alexandre Parodi, Minister of Labour in the first post-liberation government.

Francis Blanchard

My parents, my younger brother and I lived in a flat in a narrow street, rue Clement, opposite the superb medieval market, the Saint-Germain-des-Prés Market. At the foot of our building, the Town Hall of the sixth arrondissement of Paris had hastily installed a soup kitchen around which several hundred men and some women were gathered on the opposite pavement

They waited for hours under the resigned and suspicious eye of the local police in the hope of receiving a bowl of hot soup and a chunk of bread and, for the smartest or most patient who returned to the back of the queue, a second bowl. The sight of these men and women deprived of everything made a strong impression on me, particularly because my father, who had speculated, had lost everything and my mother was compelled to return to work.

Sixty years later – I was nearly 73 years old – when I took my leave of the ILO Governing Body and the International Labour Conference during two special sittings of which I have a very vivid memory, I told the Governing Body and the Conference of my conviction that, if the ILO could be proud of its past which had earned it the award of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1969, it was only in the future that it would come fully into its own. I did not realize how truly I spoke.

Indeed, I consider the date of 8 November 1989, that brutal break in history, comparable in its effects, both immediate and long-term, with that of May 1453, the conquest of Constantinople by Sultan Mehemet II which led to the downfall of the Eastern Empire.

During the night of 8 November 1989, the Berlin wall came down and with it the Soviet Empire. The ILO attained its full dimension, both geographical and ideological. Thanks to the process of decolonization following the Second World War it had achieved universal geographical coverage and also, if I dare say so, an ideological foundation based on the market economy – which is not to be confused with the wild and unrestrained capitalism which has led to the financial chasm, the economic crisis and the recession with which the world is struggling.

The last fifteen years of the cold war, during which I had the privilege of holding the tiller in a distinctly choppy sea, were marked by violent quarrels between the east, which was trying to rally the third world to its standard, and the western democracies.

Michel Hansenne

It is no insult to the Organization to observe that its reactions are slow. It is very much to the merit of Michel Hansenne that he turned to Chapter XIII of the Treaty of Versailles which contains the ILO Constitution, and in particular to its Preamble, to lead the International Labour Conference in 1998 to adopt, with the support of its President Jean-Jacques Oechslin just before his retirement from the employers’ group, the Declaration of Fundamental Human Rights at Work,

namely those incarnated in the Conventions relating to freedom of association, the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of discrimination in all its forms, the fight against forced labour and the abolition of child labour. These basic Conventions are not negotiable.

Ten years later, Juan Somavia took up the baton at a time of heated discussion on the subject of globalization. He proposed to the Governing Body to entrust to a High-Level Committee co-chaired by two Prime Ministers, the task of drawing up proposals on the topic of the social dimension of globalization, on the basis of a very well thought-out report prepared by the Office.

The day after his nomination, Juan Somavia launched a campaign under the term “decent work”. This term has the merit of being short and inviting adhesion. On the eve of the 2005 session of the UN General Assembly, a social summit was held, at the level of heads of state and government, which adopted both the concept and the term. This term refers back to the theme of the World Employment Conference of 1976 covering essential needs in the fields of work, income, education, health, housing and culture.

The 1976 World Employment Conference was held some decades too soon. It did not correspond to the mood created since 1945 by the thirty glorious post-war years, which sustained the illusion of continuous growth for the rest of the century. Such a Conference today would be a highly relevant response to the inexorable rise in unemployment resulting from the crisis. It would have to be prepared by an inter-organization secretariat.

One can hardly doubt that it was the problems resulting from the crisis and recession that formed the subject of the discussions, which, rumour has it, the Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Angela Merkel had with the executive heads of the IMF, the WTO, the OECD and the ILO, whom she had invited to come to Berlin. According to well-informed sources, she encouraged the participants to reach agreement on the policies to be implemented at the international level to ensure that economic growth and progress is compatible with social justice, a goal affirmed in numerous solemn texts

but disregarded in practice.

If social justice has an undeniable cost, as does the aggressive defense of the environment which is no longer dissociable from it in public opinion, these two dimensions of sustainable development are creative of employment and thus of fiscal revenue strengthening social protection.

Juan Somavia

Following the work of the High-Level Committee on the social dimensions of globalization and echoing the resolution adopted in 2005 by the Social Summit of heads of state and government, the Office, with the agreement of the Governing

Body, undertook a process of systematic consultations with the social partners and governments.

As a result of these consultations, the Director-General Juan Somavia presented to the 2008 Conference at its last session, a report on the achievements of the Decent Work Agenda and the strategies to follow. Following a discussion of a rare intensity, the International Labour Conference decided to give it the title of “ILO Declaration on Social Justice for a Fair Globalization”. This Declaration was adopted on 10 June 2008.

It can be seen as both a revised and updated text and as a mobilizing one capable of reaching out to all the decision-makers in the economic and social fields. It rests on four inseparable, interdependent and mutually-reinforcing objectives: employment, social protection, social dialogue and fundamental human rights. The Declaration constitutes a road map. It is a challenge for the Organization and for the Office now and for the next decades to come.

I have no doubt that the ILO will remain true to its initial choice of freedom and democracy which “is the worst form of government ever thought of, apart from all the others”, according to the celebrated formulas attributed to Winston Churchill.

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO