The ILO during World War II and the transfer of the Working Centre to Canada / Jean Mayer

Category : Centenary - Testimonials

Foreword

The following is the summary of a presentation I made on 14 March 2016 at a meeting of the AFOIT. This was based essentially on the academic thesis of Professor Victor-Yves Guebali: Organisation internationale et guerre mondiale: le cas de la Société des Nations et de l’Organisation internationale du Travail pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale (Brussels, Editions Bruylant, 2013). Some 425 pages out of a total of 800 concern the ILO, supplemented by an invaluable set of footnotes.

This vast historical epic made a slice of history itself, and one might well have feared the worst: when Ghebali died, his 1975 thesis from the University of Grenoble was nowhere to be found. It fell to his colleague and friend at the University of Geneva, professor of public international law Robert Kolb, with the help of an army of collaborators, to recreate the text from thousands of fragments of manuscript, so ensuring its scientific integrity.

It is an absolutely vital document, and all of those colleagues can be immensely proud.

The acronym AFOIT designates the French Association for the ILO (Association française pour l’OIT), whose purpose is to promote the Organization’s values to those among the French public – conference delegates, civil servants, professors, researchers – who take an interest in social justice. It seems to be the second association of this kind, after one in Japan. Founded in 2001 by Jean-Jacques Oechslin, it is currently chaired by Gilles de Robien.

In addition to the exchange of information and presentations by its members or invited outside specialists, the AFOIT organizes study tours to Geneva for students and academics. It also presents the annual Francis Blanchard Prize, worth a substantial sum, awarded for an original study that is international in scope and written in the French language.

1933: Awareness of emerging perils

It all began with the fear, then terror, of a resurgence of global conflict. Significantly, the Reichstag fire in February 1933 sparked the withdrawal of Germany from the League of Nations. Instituted by the 43 Allied and Associated Powers on the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919, the League had found Germany responsible for the violation of the peace. The brand new Palais des Nations had a relatively promising beginning, but its skies suddenly darkened one misty morning in October 1933.

Here it was that around 100 delegates endured a barrage of invective from Goebbels, whom the new German chancellor Hitler was soon to appoint Reichsminister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda.[1] With a shamelessness that sent a chill through his audience, he offered this justification for Germany’s decision to withdraw from the League in October 1933 (a withdrawal that was perfectly legal provided two years’ notice was given and no recourse made to war, two conditions that manifestly were not met): “Gentlemen, a man’s home is his castle. We are a sovereign State. We will do what we want with our socialists, our pacifists and our Jews, and we are not subject to any control, whether from mankind in general or the League of Nations in particular.” A prompt response in verse came from poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht: “O Germany, pale mother! / How have your sons arrayed you / That you sit among the peoples / A thing of scorn and fear!”

Albeit more discreetly, Germany withdrew from the ILO as well[2] with, notably, Austria, Italy, Japan and Spain following suit shortly afterwards. It was only after the cessation of hostilities that they all rejoined the Organization. For years, these withdrawals severely hampered the ILO in terms of financial resources. Indeed, Germany and Japan resumed payment of their contributions only in 1951, Russia in 1954 and Spain in 1956.

Subsequent events swiftly confirmed the worst apprehensions. In November 1937 the so-called Pact of Steel was signed, allying Germany with Italy and Japan. The years 1938 and 1939 saw a downward spiral, with the Munich agreement, followed by Hitler’s invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939, and France and England declaring war on Germany. In 1940, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg capitulated, with France being forced to accept an armistice and divided into two zones. Within the echo chamber that Geneva had become, not only the international community and the media but also the general public realized that a major conflict threatening democracy was now imminent. Even Switzerland, despite its neutrality since the Rütli oath of 1291, seemed in danger of being surrounded or invaded.

Reaction of the ILO

Faced with these events, what was the response of the successive leaders of the ILO, and how did they manage to safeguard the Organization, its values and its staff?

Let us first revisit the place where those initial decisions were taken: the ILO no longer occupied its original building on Avenue Appia (La Châtelaine, Thudichum Boarding School – now the ICRC headquarters), where Albert Thomas settled in after his election at the ILC in Washington in November 1919.[3] From 1926, it was installed in a new building, the work of a Lausanne architect in a neoclassical style, on the right bank of the lake on the Rue de Lausanne. Since the ILO’s move to Grand-Saconnex in 1974, it has been the headquarters of the International Trade Organization.

We should also recall the Office’s first two decades, while touching on the life and work of our first Director, Albert Thomas. Born in 1878 into a large family in Champigny-sur-Marne in the suburbs of Paris, his father a baker, he quenched his thirst for education by the light of the oven. He attended the Michelet lycée in Vanves where he won a scholarship in history and geography. At the Ecole Normale Supérieure he studied history, going on to obtain a doctorate in law before authoring histories both of German trade unionism and the Second Empire. It was at this time that he met Léon Blum of La Revue Blanche and Charles Péguy of Les Cahiers de la Quinzaine, as well as Arthur Fontaine, later to chair the ILO Governing Body from 1919 to 1931 and serve as leader of the Government group.

Next came his political period: he became a municipal councillor, mayor, then MP. In this last capacity, he took part in October 1919 in the parliamentary debates on the Treaty of Versailles. Ratification was obtained by 372 votes to 72. Thomas abstained, presumably (Ghebali does not address this) so as not to widen the open divide in his own party, the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO). In late 1920 at the Tours Congress, the split, between reformists and the supporters of Léon Blum, become permanent. Blum, his confirmed adversary, was only too happy to see Thomas exiled to Geneva.

Earlier, in May 1915, President of the Council[4] René Viviani, having tasked Albert Thomas with an inspection report on national defence, was so satisfied with the result that he made him Undersecretary of State for Artillery and Military Equipment. This was expanded a year later, under the presidencies of Aristide Briand then Alexandre Ribot, with his appointment as Minister of Armaments and War Manufactures.

Henceforth, proclaiming long and loud his slogan “Peace through War”, he concentrated his efforts in two directions: tripling manpower in the metalworking industry, now controlled by the State; and boosting the daily production of shells from 36,000 to 100,000. He nevertheless sought to mitigate those efforts with protective measures such as the prohibition of nightwork for women (who accounted for a quarter of the workforce), lessening of male/female wage differentials, compulsory arbitration of wage claims, and worker representation. It was hardly surprising, therefore, that the first Director – elected at the inaugural ILO Conference in Washington in October 1919 “for his enthusiasm and dynamism” – saw to it that such concerns were included in 27 of the first 33 ILO Conventions which he had to promote.

Twenty years later, the Organization was to owe its salvation to other larger-than-life characters.American John G. Winant was a personal friendof President Roosevelt, who had entrusted him with piloting the New Deal social security programme; a four-term governor of Wisconsin, he had instituted social legislation in the state.[5]

British classicist Harold Butler had a brilliant mind: a first-rate diplomat and orator, as well as a theoretician of the international civil service, he served as Thomas’s deputy before becoming his successor in 1932; as co-author of Part XIII of the Versailles Treaty, on labour, he also participated in the famous formulation of the Declaration of Philadelphia at the 26th ILC in May 1944, “labour is not a commodity”, later enshrined in the ILO Constitution. Irish physicist Edward J. Phelan, one of the authors of that Constitution and a close collaborator of Albert Thomas, became Deputy Director in 1939 and successor to Winant from 1941 to 1948.

At the operational level, Wilfred Jenks, an internationally renowned lawyer after coming down from Cambridge, co-author with Phelan of the Declaration of Philadelphia as well as the principal architect of the international labour standards, and possessing a perfect knowledge of the Organization’s strengths and weaknesses, was Director-General from 1970 to 1973.

So it was with good reason that in February 1939 it was Jenks whom the Governing Body nominated to head up a committee charged with defining the measures to be taken in the event of an emergency. A reduction in the number of posts seemed likely to be the first of these, owing to the financial crisis precipitated by the departure of half a dozen developed countries: sure enough, decisions were taken to abolish 44 permanent posts, suspend the contracts of officials called up by their national armed forces – lowering the total from 498 to 316 – and make a 15% expenditure cut to the previous budget while maintaining the same level of activity. These decisions received support in principle from the three constituent groups, both in Geneva and at the 1939 Havana Regional Conference, despite the Employers’ continuing refusal to approve the relevant budget.

At the same time, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs was sounded out about the possibility that the department of Allier, and more precisely the town of Vichy, might constitute a safe haven. The thinking behind this hypothesis centred on the spa resort’s logistical assets (accommodation capacity, immediate availability of office space, telephone network) – the same assets that were to make it the seat of choice for the government of Marshal Philippe Pétain.

As the situation worsened, ambitions were scaled back to a mere one-year lease of the town’s Pavillon Sévigné hotel, intended for the evacuation of 50 officials in the event Switzerland was invaded. The government headed by Pétain having settled in Vichy in June 1940, however, John G. Winant took the decision to cancel this rapid departure from Switzerland.

For their part, the federal authorities in Berne, profoundly attached to the defence of their neutrality and fearful of losing the more prestigious of the two organizations headquartered in Geneva, fluctuated between two positions: on one hand, the requirement to maintain all ILO staff there, as well as those of the League of Nations of which the Organization formed part (Articles 392 and 397 of the Treaty of Versailles); on the other, the threat of an ultimatum whereby our officials in their entirety would be summarily expelled following any invasion of Switzerland.

With remarkable persuasive force, Winant asserted that the temporary transfer of strictly indispensable staff to the Working Centre in Montreal would be perfectly legal, on the understanding that the Office per se would be maintained in Geneva by officials responsible for liaison and archives.

The counter-example of the League of Nations

The quality of these remarkable ILO leaders highlights the disastrous role played by the League of Nations Secretary General from 1933 to 1940, Joseph Avenol of France: in the judgement of his staff, “the wrong man in the wrong place at the wrong time”. As a result of his open sympathy for the Axis powers, he refused the refuge offered to the League by Princeton University in June 1940 in order not to miss the opportunity of refashioning the organization around a nucleus of Nazi Germany, Vichy France, Francoist Spain and Fascist Italy. Having purged the staff of dissenters from the New Order, he lost his organization 85% of its officials – not least the British ones – and its publication revenues. On his return to France in 1940, he offered his services to Pétain, without success. At the San Francisco conference, which founded the UN out of the rubble of the League in May 1945, his presence was naturally considered undesirable.

Preparations for the ILO’s departure

Back to the ILO, now home to interminable internal and external discussions about a possible destination for the transfer of a number of strictly indispensable officials. In this context, the very word “choice” is inappropriate, with the few names advanced coming up against a material or political objection: San Miguel, an island of the Portuguese Azores, was dismissed because of its small size and remoteness; London was located at the very heart of the conflict; the US was reluctant to propose Washington because of the probable refusal of the Senate to grant immunity to the half of the workforce that came from belligerent countries; nor was Latin America selected, despite its proximity and the fact that as the only long-decolonized subcontinent, divided into some twenty States, it was particularly conducive to a wide range of activities which had hitherto been neglected.

It was not until June 1940 that, thanks to the good offices of Great Britain, John G. Winant was able to opt for Canada, thus helping to strengthen social policy in North America because of its level of development and the quality of its democratic rulers. Montreal, “bilingual like Geneva”, proved to be the only solution that immediately suited everyone.

ILO Working Centre in Montreal, 1940

In August 1940, the decision was formalized by the Director, who informed all member countries of the imminent transfer to Montreal, even though it was impossible to obtain the agreement of the chair of the Workers’ group – a situation that became known as “Winant’s roll of the dice”. Finally, the question of privileges and immunities was settled without problem by the Canadian Government in August 1941.

Of the 63 officials opting for voluntary separation, 40 were retained, from 18 nationalities, some 8% of the total complement. All other contracts were suspended (especially of those who had been called up) or terminated, the statutory indemnities due being spread over several years.

From Geneva, via Lisbon and an Atlantic crossing, to a home in Montreal

The party of remaining ILO officials and their families set off in October 1940, the initial journey taking five days by train and bus. They encountered no difficulties at any of the border crossings, even in Spain, barred from the League of Nations because of its attitude during the civil war, and Portugal. The group had to wait a month in Lisbon (the photos can be seen on the web), both for the docking of their ship from Greece, which had joined the Allies, and pending the outcome of negotiations – conducted for the ILO by ADG Adrien Tixier – with the Vichy government, which opposed any French official’s departure for Canada or any other belligerent country.

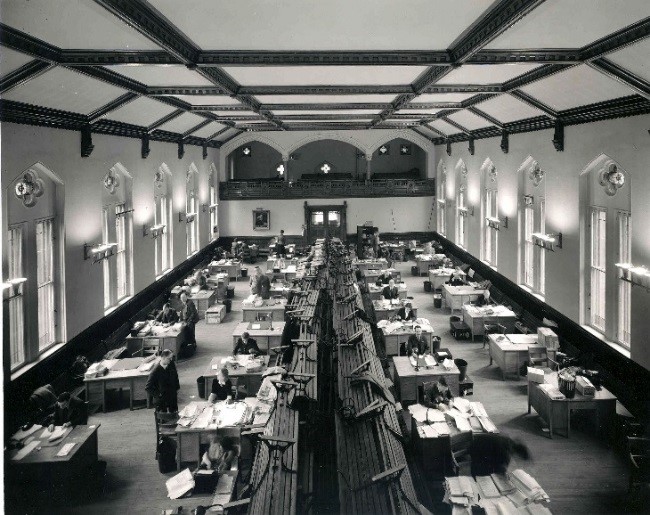

The ILO party landed in New York before continuing by train to Montreal, with the French having to remain in the United States, at least temporarily, given the ban by Vichy. The rest of the group moved to a disused chapel at McGill University. (In 1967, participants in the Ottawa Regional Conference – in which I was able to take part with my counterpart after my first expert mission, in Chile – had an opportunity to discover these historic sites, with no little emotion.) In 1941, John Winant, renowned as someone who got things done, judged that he had seen the transfer to Montreal successfully through and left the ILO to become US ambassador to London. Edward Phelan, his deputy, succeeded him through till 1948. Two articles by Phelan – “The ILO sets up its wartime centre in Canada” and “The ILO turns the corner”, republished in Edward Phelan and the ILO (ILO, 2009) – provide an excellent description of this difficult period.

The ILO Working Centre in Montreal

Although it had lost two-thirds of its customary scope for action and shifted its focal point from Europe to the Americas, the ILO managed to maintain a satisfactory level of functioning, mainly thanks to its budgetary resources and the fact that the Employers’ group, which did an about-turn when it realized the importance of the Organization in a war context, approved the budget each year. Some three-quarters of these resources came from the Commonwealth, the US, India and China, and the ILO managed to get its dues paid directly, without going through the League of Nations.

These factors contributed to the growth of the staff from 70 officials in 1941 to 143 in 1944. In addition, the existence of a network of ten ILO national offices played an appreciable supporting administrative role. Membership of the Organization remained stable: of 57 member States in 1939, 52 still formed part in 1944, despite the (temporary) withdrawal of Germany, Italy, Spain, the USSR and Japan. Conferences remained important but met less frequently: among the most noteworthy was the October 1941 ILC in New York, a city chosen to give the US (admitted in 1934) the benefit of the experience of tripartism existing among more longstanding members; 34 countries participated, including the eight Governments in exile in London (Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, the Netherlands, Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg and Greece, five of them members of the GB).

During this Conference, the delegate from Vichy France in Washington tried in vain to prevent the intervention of the representative of Free France, sent by de Gaulle. Phelan moreover managed to extend the competence of the ILO to economic and social reconstruction and the collation and analysis of the associated plans of 20 countries, in accordance with Article 10 of the Constitution. This ILC culminated at the White House, where President Roosevelt hosted the participants. Five maritime conferences were held in London.

Finally, the most important meeting, the 26th International Labour Conference, held in May 1944, unanimously adopted the so-called Philadelphia Declaration on the aims and purposes of the ILO. Developed by Phelan and Jenks, it was considered the most significant text since the founding of the Organization and would be annexed to the Constitution.

In the legislative sphere, two of the three procedures were changed during this period: the adoption of new standards was suspended; while the ratification of the existing Conventions took on a new impetus, visible in 18 Latin American countries; finally, the monitoring of their effective implementation by the Committee of Experts on the Application of Conventions and Recommendations, created in 1927, was made more flexible through a system of more summary information provided by the countries concerned, with a response rate of 60%.

Wilfred Jenks

Achievements

The Office was unable to exercise its capacity to carry out quasi-judicial activities (observations and sanctions, but not condemnations).

It may be recalled that there are three bodies of this type: the aforementioned Committee of Experts; the Commission of Inquiry provided for by the Constitution (Article 26), ruling on complaints between member States; and the ILO Administrative Tribunal, an industrial tribunal dealing with complaints by international civil servants against their employer. This last function was transferred from the League of Nations to the ILO following the former’s dissolution as decided at San Francisco in June 1946, with its jurisdiction extended to the staff of the UN and the many so-called specialized agencies – UNESCO for education, WHO for health, FAO for food, etc. – created after the war. In respect of violations of trade union rights, the Committee on Freedom of Association was not established until 1951.

Article III of the Declaration of Philadelphia (“the solemn obligation… to further [programmes] among the nations of the world”) provided for technical advice to be provided to member countries, an activity which would take off spectacularly after the war in the form of technical cooperation/assistance, financed largely partly by UNDP. At the time, this was limited to the area of social security: three Czech specialists covered 19 mainly Latin American countries, including Chile at the request of the Minister of Labour and Health, Dr Salvador Allende. In the same field, the ILO helped both Great Britain to develop the Beveridge Plan, and Free France, established in Algiers, to totally overhaul the Vichy government’s Labour Charter. In addition, Rens, the Belgian member of the Workers’ group in the GB and future Deputy Director-General, successfully launched the Andean Development Plan in four countries of the subcontinent.

The ILO was unable to organize regional conferences in North and South America as it did in Havana in 1939. But – more importantly – it did, like the US, Great Britain and France, participate as an observer at the conferences in Dumbarton Oaks (Washington, DC) and Bretton Woods (Arkansas, June-July 1944) that created the IMF and the World Bank, forerunners of economic globalization.

The ILO, which had been invited only as an observer and without trade union participation, not only protested but expressed its astonishment that the objective of full employment was not mentioned at all. In fact, it took thirty years for both organizations’ strategies, as advocated and clarified by the ILO World Employment Conference (1976), to change position. A tripartite delegation took part in the San Francisco Conference (June 1945) which founded the United Nations, made the ILO the first specialized agency (despite Russia’s opposition, based on its hostility to tripartism) and adopted the UN Charter.

Three years later, meeting in Paris, the United Nations pursued this founding legislative task by adopting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which includes, in addition to civil and political rights, the economic, social and cultural rights treated by the ILO in conventions on the right to work, equal pay and freedom of association. Finally, regarding these two clusters of rights, in 1966 the United Nations adopted two Covenants, ratified by three-quarters of the planet, emphasizing the fundamental nature of these rights and allowing for the sanctioning of violations. In addition, thematic technical meetings were organized, such as 1942’s inter-American meeting in Chile on social security, and another in 1943 that brought together ten countries in Montreal on the internationalization of the social security model, opening the way for the 1944 ILC in Philadelphia to make it mandatory.

In terms of information, the record was very positive: the press service reached 700 Canadian and American newspapers and magazines, and the number of publications doubled (in comparison, those of the League of Nations dropped by 90 per cent). The ongoing publications programme – which included coverage of national reconstruction plans – earned appreciation, in particular the Yearbook of Labour Statistics and the International Labour Review, which was even the subject of a pirate edition in German, bearing a swastika on the cover.

The ILO leadership, on the other hand, was aware of the Organization’s lack of preparedness to undertake research on social policy instruments that incorporated the international economic dimensions it had been advocating, which were not usually tackled by Ministries of Labour. In fact, during its first decade of existence, the ILO research programme successfully confined itself to the collation and publication of statistics on employment and unemployment, thanks to the recruitment of experienced specialists.

Return to Geneva after the war

The Montreal staff’s return to Geneva took place in successive waves over the course of 1945. Numbering 40 when they left for Montreal, a total of 150 came back. In his memoirs, Francis. Blanchard dates the restoration of the Office in Geneva to 1948. It is notable that no one attempted to start an “ex-Montrealers’ club”. This had been a high-risk trial for the ILO, and it was never mentioned again. Twenty-five years later, with the departure of David Morse (Director-General from 1948 to 1970), the staff of the Office had grown from 140 to 1,500 officials, plus an equal number of experts in technical cooperation projects in the field; as of 31 December 2016, it stood at a grand total of 2,903 staff members worldwide: 1,155 at headquarters (including 216 on TC contracts) and 1,748 in field offices (including 970 on TC contracts).

ILO attributes

The remarkable success of the ILO during the war years is due to many factors:

- basic assets: its credit emerge being intact, if only by comparison with the League of Nations; its broad membership, including the United States; direct and permanent contact with public opinion, thanks to its tripartism; appropriate preparations for the state of war;

- endogenous factors: a flexible, non-legalistic approach to problems; a degree of foresight; leadership of exceptional quality; team spirit among the staff; the success of the New York and Philadelphia Conferences; motivation among delegates;

- exogenous factors: the increasing weakness of the League of Nations; the alignment between the social ideals of the ILO and the ideology of the member States engaged in the war; the ILO’s commitment to the Allied cause.

So it was that Roosevelt was able to say: “The ILO synthesized the aspirations of an era marked by two world wars.” Or in the words of Winant, his compatriot: “The transfer brought us freedom of thought, assembly and movement.”

[1] Hitler acceded to the post of Chancellor of Germany in January 1933, becoming head of State – Führer – in 1934

[2] It announced its withdrawal in November 1933, effective 1935.

[3] For the election of Albert Thomas see the above article by Carl V. Bramsnaes., pp. 11-13.

[4] As the Head of Government was known in the Third French Republic.

[5] For John G.Winant, see above article.

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO