Second illustrated contribution to the ILO centenary / Natan Elkin

Category : Centenary - Testimonials

It says in Don Quixote that “second parts are never any good”, which should have discouraged me from writing this second contribution following the resounding success of my first contribution to the Centenary of the International Labour Organization.

The discovery of new photographic evidence of the Latin American delegates and an encounter with Liza Burgos, a descendant of the Panama delegate at the Peace Conference, prompted these few lines. Dr Martínez Ortiz’s hair, Antonio Sánchez de Bustamante’s gaze and Antonio Burgos’ head moving while Clemenceau spoke to the delegations at Trianon and Saint-Germain-en-Laye justify this new reflection before the ILO centenary comes to an end.

My research also uncovered the first statement on the prospects of the future of work, which was given by a British delegate on 14 February 1919. My loyal readers will also learn that, on 1 February 1919, George L. Berry, future Democrat senator for Tennessee, appeared in the photo of the Commission on International Labour Legislation.

In this document, I have new information about the Polish count, Jota Zoltowski, and offer the chance to access the film of my trip through the lands of the Potocki counts, recalling, in this centenary year, of the book on international labour standards published by Geraldo Von Potobsky and Héctor Bartolomei.

A new photo of Dr Martínez Ortiz

In my previous post, I developed a thesis with two hypotheses: the only photo of the Commission on International Labour Legislation in which the Cuban delegate, Dr Rafael Martínez Ortiz, can be discerned had been taken either on Saturday, 25 January 1919 or on Saturday, 1 February 1919. Indeed, these were the only two days that the distinguished representatives of the Czecho-Slovak Republic (Edvard Benes) and the Republic of Cuba (Rafael Martínez Ortiz) were in attendance at the meetings of the Peace Conference.

Following in the footsteps of Stanley Taylor, who developed a passion for uploading his private collection of L’Illustration on the site for former officials of the ILO, I also decided to look for more documents in my mother-in-law’s personal collection of the French newspaper.

According to L’Illustration, at 3 p.m. on Saturday, 25 January 1919, Henri Poincaré, President of the Republic, opened the Peace Conference in the Clock Room of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

L’Illustration published an eloquent description of the event:

Les peintres d’histoire éterniseront cette scène unique. Comme cadre, le ministère des Affaires étrangères. Plus précisément, le salon dit de l’Horloge, au rez-de-chaussée du ministère. On y accède par les deux perrons de la façade, quai d’Orsay. Le salon, comme l’ensemble des appartements, date du Second Empire. Il est rouge et or. Ses trois larges fenêtres, encadrées de rideaux de soie à ramages, ont vue sur la Seine et les Tuileries. Au fond, une immense cheminée de marbre dans laquelle est encastrée l’« horloge ». Face aux fenêtres, trois baies font communiquer le salon avec une galerie.

Rafael Martínez Ortiz is seen from behind, on the right edge of the photo, sporting his thick, white hair. With a little concentration, one can make out the beginning of his famous moustache. According to the seating plan published by L’Illustration, Martínez Ortiz occupied seat 29. The seats of the delegates of Guatemala and Panama, which were on the other side of the horseshoe, were without their occupants, Joaquín Méndez and Antonio Burgos.

Dr Martínez Ortiz seems to have fixed his gaze on Lieutenant Paul Mantoux, the officer interpreting Poincaré’s opening statement. While Martínez Ortiz’s attention is focused on the speech, his back is turned, allowing his thick, white hair to be admired by the honourable Joao Pandiá Calógeras, who would later be thought of as the “Clausewitz of Brazilian foreign relations”. Sitting on Martínez Ortiz’s right is the Greek Minister for Foreign Affairs, Nicolas Politis, who immerses himself not in listening to the interpretation of the speech but in reading something likely more productive.

Opposite Martínez Ortiz, on the other side of the table, are the three chairs reserved for the Belgian delegation, although only two delegates were present that day: Paul Hymans, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Jules Van den Heuvel.

At the end of Poincaré’s speech, President Wilson proposed — and those present raised their hands in agreement — that Georges Clemenceau be elected president of the Conference. L’Illustration’s reporter noted a mistake by the interpreter, who had Lloyd George saying that he considered Clemenceau to be “France’s greatest old man” before correcting it to “Mr Clemenceau is France’s grand young man ”. The report concluded that: All that remains is for the delegates to go and have a cup of tea together. The big day ended on friendly terms. The meeting close at 4.50 p.m.

There were three items on the Conference agenda, which would be dealt with in committees: (1) responsibility for the war, (2) penalties on crimes committed during the war and (3) international legislation in regard to labour. All three were new issues, with social matters taking on equal importance with military matters.

In front of President Wilson, and on behalf of the English world of work, Barnes heralds “the rising dawn”

In its 22 February 1919 edition, L’Illustration recorded the moment when the attention of world leaders was focused on the newly formed ILO. Before returning to Washington on 14 February 1919, President Wilson read the provisions that had been adopted to create the League of Nations.

The drawing in L’Illustration shows the minister Georges N. Barnes, one of the leaders of the Labour Party, “with his very short-sighted eyes, his honest and lively face”, who, referring to the newly-formed ILO, calmly declared that:

You will be generous, impartial, altruistic, without imperialist selfishness; you will be concerned about workers’ wages and their working conditions.

Those words about the ILO are still relevant today.

In 1919, Georges N. Barnes was the first Briton to make a statement about the future of work, gaining the attention of Wilson, Clemenceau and Balfour, and of the delegations present at the Paris Conference.

Two soldiers in the photo of the Commission on International Labour Legislation, 1 February 1919

It always seemed to me that there were at least two extra people in the photo of the Commission on International Labour Legislation: two people in military uniform, one on the far left and the other on the right of the photo, on the second row.

The soldier on the far left of the second row is an American. The vignette in the ILO Archives refers to him as “Gordon L. Berry” and a Gordon Lockwood Berry certainly existed. On 7 January 1932, the New York Times published an obituary about Gordon Lockwood Berry recalling that, among other things, Gordon Lockwood Berry had worked for the League of Nations in the humanitarian operation that enabled 22 million children to be transferred from Turkey to Greece.

However, documents published by the US State Department’s Office of the Historian, in the “Labor Section of the American Commission at the Peace Conference”, refer to a “Liaison Officer: Major George L. Berry, U. S. A.”.

George L. Berry, a Democrat senator at the inauguration of the ILO.

George L. Berry was a prominent trade unionist, with links to Sam Gompers. He was also senator for Tennessee in 1937-1938. The US Senate published an eloquent summary of his life:

BERRY, George Leonard, a Senator from Tennessee; born in Lee Valley, Hawkins County, Tenn., September 12, 1882; attended the common schools; employed as a pressman from 1891 to 1907 in various cities; served during the First World War in the American Expeditionary Forces, with the rank of major, in the Railroad Transportation Engineers 1918-1919; president of the International Pressmen and Assistants’ Union of North America 1907-1948; also engaged in agricultural pursuits and banking; delegate to many national and international labor conventions; appointed on May 6, 1937, as a Democrat to the United States Senate to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Nathan L. Bachman and served from May 6, 1937, to November 8, 1938, when a successor was elected; unsuccessful candidate for nomination in 1938 to fill the vacancy; resumed the presidency of the International Pressmen and Assistants’ Union of North America, and also his agricultural pursuits at Pressmen’s Home, Tenn., until his death on December 4, 1948; interment in Pressmen’s Home Cemetery.

In this Centenary, with the kind assistance of Fiona Rolian and other ILO Friends on Facebook, the Organization has succeeded in identifying other figures of the Commission on International Labour Legislation.

More should have been made of the career of George L. Berry during the Centenary celebrations. It is not often that a person linked to the ILO occupies a seat in the US Senate.

Colonel Lister: a Comintern agent in the photo?

The person on the right of the photo bears the name of a Comintern agent: Colonel Lister, about whom terrible things are said in all the books about the Spanish Civil War and who was not thought of fondly by Jorge Semprún either. It couldn’t be possible that a Spaniard in uniform, even with Soviet training, could have slipped into the Peace Conference.

The solution to the enigma is found in L’Illustration, the 3 May 1919 edition, which provides us with a photo of three individuals: Colonel Lister, of the British army, French Colonel Henry and Mr. Oudaille. These three were gathered in the royal gardens of Versailles to receive the German delegation summoned to sign the conditions for peace.

The Colonel Lister in the photo of the Commission on International Labour Legislation was Lt. Col. Frederick Hamilton Lister (1880-1971). This excellent summary is from the military archives:

Born 1880; educated at Radley College and Royal Military Academy, Woolwich; commissioned into Royal Artillery, 1900; seconded for service with the Punjab Frontier Force, India, 1902-1911; Capt, 1911; graduated from Staff College, Camberley, Surrey, 1914; served in World War One, 1914-1918; posted to General Staff, 1914; Maj, 1915; awarded DSO, 1916; General Staff Officer 1, British Mission, Belgian General Headquarters, Western Front, 1917; General Staff Officer 1, General Headquarters, France, 1917-1918; Brevet Lt Col, 1918; General Staff Officer 1 in charge of British Mission to 1 French Army, 1918; General Staff Officer 1, Supreme War Council, Versailles, 1918-1919; British Representative, Allied Mission, Enemy Delegations, Paris, 1919; service in South Russia as General Staff Officer 1, British Mission to White Russian Gen Anton Ivanovich Denikin, 1919-1920; accompanied French operations in the Rif Mountains, Morocco, 1926; Lt Col, 1927; retired 1931; member of HM’s Body Guard of the Honourable Corps of Gentlemen-at-Arms, 1932-1950; died 1971.

Although the little French colonel Henry is hiding his hands, he is not Colonel Hubert Henry, who had played such a terrible role in the Dreyfus Affair and died long before, in 1898. The research of Bertrand M. enabled me to identify an officer named Edmond François Henri (1872-1931).

The Counts Zoltowski and Potobsky in Argentina

On the left of the Commission on International Labour Legislation photo, in the second row alongside the future Senator George L. Berry (in American military uniform), is Guy H. Oyster, the private secretary of Sam Gompers, and, next to him, Count Zoltowski.

In the minutes of the Commission on International Labour Legislation, it is said that Count Zoltowski answered to the name of Jean. The question is how certain is it that Count Zbigniew Zoltowski, who was buried on 16 February 1973 in the suffocating heat and humidity of Recoleta, is the same person who endured the Parisian cold of 1 February 1919?

According to information from specialist sites, the Zoltowski family received the countship quite late, in 1840, which rules out the likelihood that the Zoltowskis counts would have greatly multiplied by 1919.

The other information that I found out about Count Zbigniew went along the same lines:

Polish diplomat and Count. He was Plenipotentiary Minister of Poland in the exile in Argentina, during the communist regime in his country. Together with his son Jan was able to bring humanitarian aid to Polish refugees in Europe through the Red Cross and also attended Polish political refugees in Argentina. He was awarded by the Polish Government in London with the great band of the Order of the Rebirth of Poland.

The Zoltowskis’ title could be inherited by the firstborn child, which explains why, on announcing the death of his son, on 21 April 1988, Jan Damascen Edmund retained the title of Count (and a Knight of the Order of Malta). Jan is the Polish version of Jean, the name his father identified with at the Peace Conference.

Jan married an Argentine woman whose name seems predestined to celebrate the ILO centenary and the future of work: María Luz.

Unlike her distinguished father-in-law, who had participated in drafting the founding constitution of the ILO, the three families represented by María Luz’s surnames — the Obligado, Nazar and Anchorena families — left no specific souvenir of their contribution to social justice. Had they put their estancias on the humid Argentine Pampas to full and productive use, they could have certainly helped reduce world hunger.

In any case, another honourable representative of a Polish count’s family was very much involved in the international labour standards, as borne out by a book published in Buenos Aires in 1990. Geraldo W. Von Potobsky, known at the ILO as Von Pot, was chief of the freedom of association service.

In the eighteenth century, the Potocki counts ruled over the vast territories of Polish Galicia, where Jewish communities had lived for centuries before being systematically exterminated between 1939 and 1945.

So, why should a book published by an Argentine descendant of the Potocki counts and my friend Héctor Bartolomei, with a prologue written by Dr Ruda (President of the International Court of Justice and of the Commission of Experts), deserve a mention in this note on the ILO Centenary? The answer can be found in the film of my trip through Galicia (now in Ukraine) and Bessarabia (now Moldova), territories that had belonged to the Potocki counts and from where, after the most atrocious crimes had been committed, the concepts of genocide and crimes against humanity emerged. During the same trip, in Bessarabia, I visited the hometowns of the family of the Minister of Justice who abolished the death penalty in France.

At Trianon: the presentation of the peace terms to the German plenipotentiaries

In the book Contrastes europeos y orientación americana, published in Rome in 1925, Antonio Burgos recalls that it was “one of the most exciting acts that I have ever attended. At the main entrance to the historic palace, every delegation was received with full military honours by a resplendent French regiment; doorman in traditional uniform gently guided the Allies’ plenipotentiaries to the meeting room. The room was not especially sumptuous, featuring thick damask curtains, a simple tapestry adorned with a historical portrait and, in the centre, a large table in the form of a horseshoe. Seated at the head of the table was Clemenceau, with Wilson on his right and Lloyd George on his left. The other Allied delegations took their places on the sides of the horseshoe and, at the bottom edge, were eight or nine empty seats for the German plenipotentiaries”.

Although the ceremony had barely begun, Antonio Burgos, a perceptive diplomat of a young Republic, was already pondering the consequences of the events he was witnessing.

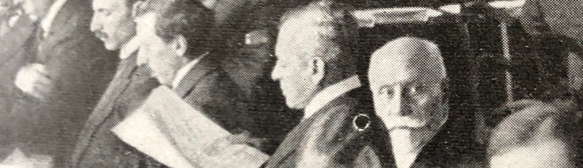

While Clemenceau gave his speech, Antonio Sánchez de Bustamante, seated at the end of the left side of the horseshoe, with his white beard and moustache, fixes his gaze on the French leader. Next to him, the silhouette of Joaquín Méndez of Guatemala, looking straight ahead, can just be seen, followed by the delegate of Haiti, Tertulien Guilbaud; the former President of Honduras, Policarpo Bonilla; the delegate of Liberia, Charles D. B. King; and, from Nicaragua, a member of the Chamorro family. Like Antonio and Tertulien, Salvador Chamorro is looking at Clemenceau.

The only delegate ostentatiously avoiding looking at Clemenceau, by turning his head towards the German delegation, is Antonio Burgos of Panama.

A few years later, Antonio Burgos reflected that “the absurdities contained in the Treaty of Versailles were revealed to the world when the document was still just a project being discussed by the interested parties. One by one, the events that have occurred have confirmed the reasonable predictions that were made by the Treaty’s critics”. To support this position, Burgos cites his own impressions and the publications of three eminent Europeans: L’Europa senza pace, by Francesco Saverio Nitti; War Memoirs, by David Lloyd George; and The Economic Consequences of the Peace, by John Maynard Keynes.

In the Stone Age Room: the presentation of the peace terms to the Austrian plenipotentiaries

In its 7 June 1919 edition, L’Illustration recounts the event in which the peace terms were presented to the Austrian plenipotentiaries at Saint-Germain-en-Laye Castle:

[…] C’est une étrange pièce qui porte à l’entrée cette indication gravée : « Salle de l’âge de pierre ». Il y avait là des collections d´ossements préhistoriques qu’on a enlevées pour la circonstance. Mais on a laissé des cartes murales représentant la Gaule à l’époque des cavernes et aussi des pancartes où on lit : « Alluvions quaternaires », « Ossements d´animaux d´espèces éteintes ». Bizarre mélange d’un présent dramatique et d’un obscur passé enfui dans le silence des siècles » […]

The next photo, of the left side of the horseshoe, shows Antonio Sánchez de Bustamante, with his white beard and moustache, looking towards the camera as he sits in the fourth seat of the second row of the left side of the horseshoe, which constitutes the table of the Allied delegations. Joaquín Méndez, the delegate of Guatemala, is seated to his left, calmly reading a document, not paying attention to Clemenceau’s speech.

It’s not possible to distinguish Burgos, who is sitting in the same row as Méndez and Sánchez de Bustamante, in the third seat from the head table.

There’s a nice story on Wikipedia about Joaquín Méndez. In 1914, Méndez was ambassador to the United States when he found out that Rubén Darío was down and out in New York. Darío had tried to earn a living giving talks to promote peace in Europe.

In one of the works published in the Studia in honorem Lía Schwartz (University of La Coruña, 2019), the information about Rubén Darío’s attempted pacifist venture on his arrival in New York in 1914 is corroborated. Having spent three years in Paris, and having abandoned his wife and son in Barcelona, Rubén Darío and Alejandro Bermúdez, his secretary, presented Archer Milton Huntington with a proposal for a project called “PROPAGANDA PARA LA PAZ A TRAVES DEL CONTINENTE AMERICANO” (advertising for peace in the American continent).

The two intrepid Nicaraguans were seeking funding for 46 lectures aimed at denouncing the indescribable carnage in Europe and promoting peace, which should be “the supreme ideal of every good man and the highest aspiration of the peoples”. The talks would make visible “the need for the American people, led by the United States and in agreement with Spain, to be the first to manage peace in Europe, since special circumstances favour such lofty and plausible goals”.

Anticipating the daily tasks of any self-respecting international civil servant, the amount requested for giving 46 lectures was $50,000, which, in August 2018, is equivalent to just over $1.2 million, according to the precise calculations of professor Alison Maginn, of Monmouth University, in “Rubén Darío’s Final Chapter: Archer Milton Huntington and the Hispanic Society”, one of the works published in honour of my aunt, Lía Schwartz. Anyone who has watched the film of my trip to Galicia and Bessarabia in its entirety will have seen extracts of the tribute paid to Lía at the Instituto Cervantes in New York on 30 April 2019.

Despite Huntington’s efforts, by April 1915 Rubén Darío was sick and penniless in New York. Three people took care of him: Juan Arana Turrol, a poor and unrenowned Colombian; Salomón de la Selva (1893-1959), a Nicaraguan poet, a British soldier during the Great War and a union leader, alongside Sam Gompers, who set up unions in Nicaragua and Mexico. Salomón died suddenly in Paris, where he was Nicaraguan president Somoza’s ambassador; and Joaquín Méndez, the ambassador of Guatemala.

Thanks to the personal efforts of Joaquín Méndez, and the generosity of the Guatemalan Government, Darío moved to Guatemala in April 1915 and returned to Nicaragua several months later to die, according to Eddy Kuhl in “Aventura pacifista de Rubén Darío en Nueva York en 1914-1915” in Revista de temas nicaragüenses (March 2012).

I would like to conclude with some poetry

Despite his financial uncertainties, on 4 February 1915, in Havemeyer Hall at Columbia University, Rubén Darío read Pax!, a poem that contains this verse:

Se grita: ¡Guerra Santa!

acercando el puñal a la garganta,

o sacando la espada de la vaina;

y en el nombre de Dios,

casas de Dios en Reims y Lovaina

¡las derrumba el obús 42!…

To coincide with celebrations commemorating the Armistice of 11 November 1918 that formally ended the hostilities of the Great War, in November 1976, I travelled from Leuven to Paris, stopping at Reims. As I so often recount, it was in Paris that I began what was to become an enduring a romance with a young Parisian woman.

Reims Cathedral was effectively bombarded. However, as all Latin American students who arrived in Leuven in the Seventies well know, it was not a house of God but the library of the Catholic university that was destroyed by the imperial shells.

In this centenary year, I also wanted to preserve the name and memory of the valuable members of the Commission on International Labour Legislation that met on 1 February 1919 in Paris in order to draft the ILO Constitution.

The Cubans distributed sugar and dreamed of setting up orphanages for the Belgian and French war orphans. Rubén Darío fought, through his poems, for world peace.

A universal and lasting peace with social justice, as written on the fronton of the ILO for the next hundred years.

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO