Harold B. Butler (1883-1951) studied at Oxford, entered the British Civil Service 1907; Ministry of Labour 1917 as Assistant Secretary to the Minister. In 1918 he, Phelan and Malcolm Delevigne drafted a programme for the Labour Section of the Paris Peace Conference. In 1919 he was appointed Secretary to the Organizing Committee and Secretary-General of the First Session of the ILC in Washington, DC. In the early years of the ILO he served as Deputy Director of the Office, with responsibility for administration and finance. In 1932 he succeeded Albert Thomas as Director of the ILO. He resigned in 1938 and became Warden at Huffield College, Oxford. Commissioner for Civil Defense 1939 to 1941 and Minister at the British Embassy in Washington D.C. from 1942 to 1946.

Butler had a considerable influence on the work of the first Conference. As Edward Phelan later was to write: “In moments of difficulty, and more particularly on constitutional and procedural questions, the Conference listened most readily to those who had planned it in Paris and to none with more attention than to the Secretary-General, Mr. Butler.

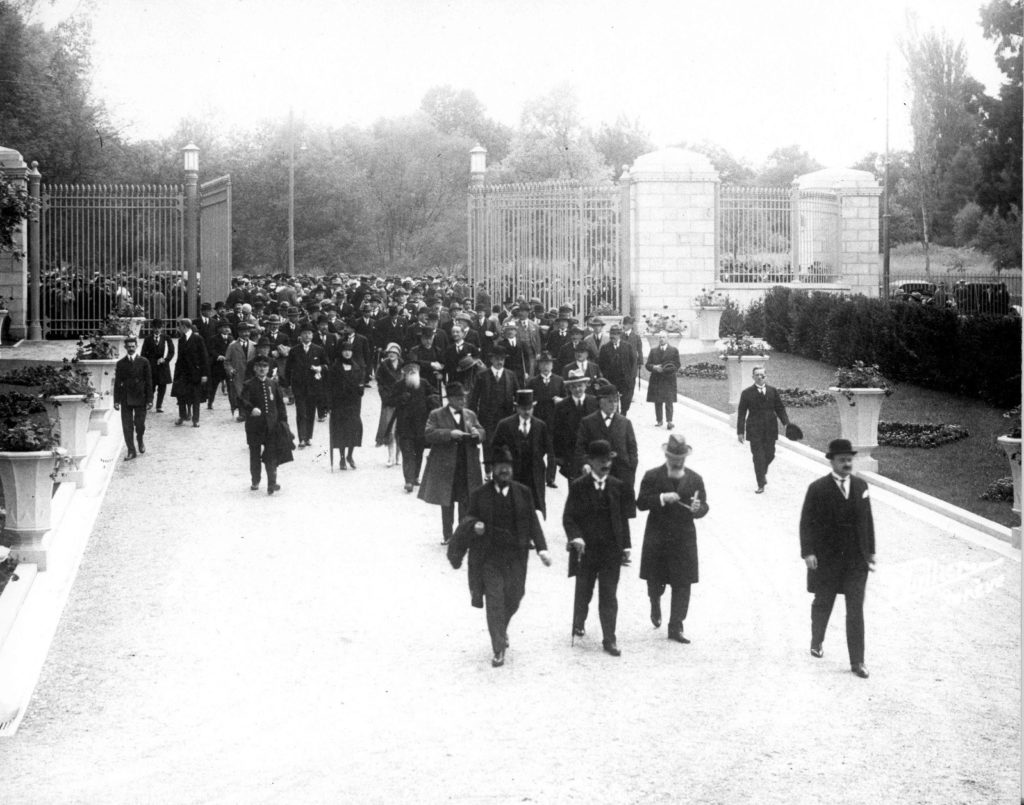

While the Peace Treaty provided for the composition of the Annual Labour Conference it left it to determine its own procedure. The Organizing Committee devoted considerable care and labour to drafting a set of provisional Standing Orders, which were adopted at the second sitting of the Conference but which were then referred to a special committee of the Conference for further examination.

This committee, after prolonged discussion, submitted a revised set of Standing Orders in 20 Articles, which were adopted by the Conference. They do not call for any detailed comment here, but they suggest two general observations. In the first place, experience has since shown the wisdom of the Organizing Committee and of the Conference in settling the parliamentary procedure of the Conference at the very beginning. Practice differs considerably from country to country.

The powers of the chairman, the method of moving resolutions, the method of voting, the application of the closure, are all matters of vital importance to the proper conduct of any gathering, but matters about which the greatest variety of custom prevails in the different assemblies of the world. As the Committee observed:

It has not been possible to find in every case a rule which everyone will regard as satisfactory. This fact should be borne in mind, and it should be recognized that the procedure followed in any one country or group of countries could not be inserted in the Standing Orders.

They were, in fact, the first set of international standing orders ever framed, resting on a compromise between a large number of national practices. Although they have since been amended from time to time, they have on the whole stood the test of practical application, and have rendered great service to the Organization by providing it with a body of rules to which the members of the Conference have gradually become thoroughly accustomed. The resulting expedition in the dispatch of business and the avoidance of confusion in regard to procedure have saved the Conference many hours of time and much loss of patience.

The other point which merits notice is the emergence of the language question at the first Conference held under the auspices of the International Labour Organization. Viscount de Eza, representing the Spanish Government, put forward a plea for the recognition of Spanish as a third official language. His claim led to similar pleas put forward for the recognition of German and one of the Slav languages. In point of fact, an arrangement had already been made whereby a translation of the proceedings into Spanish was daily provided for the delegates at the expense of the United States Government. No international meeting can function effectively unless at least the great majority of its members can follow the proceedings satisfactorily. In the Labour Conference, where the delegates do not usually possess the same advantages, the necessity of interpreting the proceedings to them, as far as possible in a variety of languages, was thus early found to be imperative.

The Washington Conference set a further precedent of far-reaching importance in the future history of the Organization in recognizing the existence of the employers’ and workers’ groups. When the Treaty was drawn up it was probably not foreseen that the employers’ and workers’ delegates, being necessarily bound by strong ties of common sympathy and interest, would inevitably tend to form distinct blocs with a view to united action. In any case, no provision of the Treaty suggests that such an eventuality was contemplated. Nevertheless, before the Conference had even assembled for the first time, the two groups were already taking shape.

In the case of the employers, the germ of such an organization was already in existence. In 1911, Signor Olivetti organized the first International Congress of Industrial and Agricultural Employers’ Organizations (Congresso internazionale dell’organisazioni padronali dell’industria e dell’ agricoltura). This meeting gave birth to the idea of setting up an international employers’ information centre, and in 1913 M. Carlier and M. Lecocq, at that time President and Secretary respectively of the Comité central industriel de Belgique, got into touch with various European countries in search of support for creating such a centre. As a result of a meeting held in Paris in June, 1914, its establishment was agreed upon, with M. Carlier and M. Lecocq as President and Secretary respectively. The War prevented the realization of the project, but they revived it when the convening of the Washington Conference was announced. On reaching Washington they took the initiative, in conjunction with M. Guérin (France) and Mr. Marjoribanks (Great Britain) by inviting employers’ delegates to attend a meeting in the Navy Building on October 28, the day before the opening of the Conference. From that time onwards, it was the employers’ group thus constituted which put forward employers’ nominations for the Vice-Presidency, for the membership of committees, and, finally, for membership of the Governing Body. It decided at group meetings the policy which should be adopted in regard to most, if not all, of the questions which came up for discussion, and a series of important amendments to the draft convention on hours of work was moved on behalf of the whole employers’ group. Finally, before the Conference closed, the group drew up and signed on November 23 statutes for a permanent international organization of employers.

The formation of the workers’ group was of even more natural development and required scarcely any preparation. The International Federation of Trade Unions had just been successfully reconstituted at Amsterdam, and had taken a leading part in the negotiations in regard to the admission of Germany and Austria which preceded the Conference. Its authority was so well established as to be beyond cavil or criticism. Indeed, it had even gone so far as to demand that all workers’ delegates should be chosen in agreement with the organizations affiliated with the Federation. In these circumstances, it was natural that the leaders of the Federation, who were themselves delegates to the Conference, should act in unison and at once set about organizing their fellow workers as a disciplined group.

On November 1, two days after the opening of the Conference, M. Mertens, as president of the workers’ group, informed the Secretary-General that M. Oudegeest had been appointed as its secretary. Like the employers’ group, it held regular meetings during the Conference, and submitted a series of group amendments to the Organizing Committee’s draft of the Hours Convention. As in the case of the employers, the workers’ nominations on committees and on the Governing Body were settled by discussion in the workers’ group.

It would be out of place to develop here the important part which these natural formations have since come to play in the working of the Organization. Though at times they have been subjected to criticism on the ground that they have introduced too large an element of discipline, and thus repressed individual expressions of opinion, on the other hand it is not open to doubt that without the collective expression of the employers’ and workers’ views during the discussions of the Conference, and the joint negotiations with a view to reaching agreement which they have made possible, the solutions of its problems would have been infinitely more arduous and their outcome less satisfactory. Moreover, the existence of the groups served to preserve and emphasize the essentially tripartite character of the Conference. The result has been that it has come to view the questions before it much less from a national point of view than from the point of view of their technical merits, and their bearing on the interests of those concerned in production.

The constitution of this Committee was another happy instance of the prevision exercised by the Organizing Committee. They foresaw the necessity of creating some supreme organ of the Conference, fully representative of its various groupings, to which all questions relating to its proceedings might be referred.

By this device lengthy debates on procedure were avoided, and it was possible to reach decisions as to the general conduct of the debates, the setting up of committees, and other general questions which could hardly have been settled expeditiously and satisfactorily in the full Conference. Here again an important precedent was established, which was to prove its value in future years and to become an essential feature of every the session of the Labour Conference.

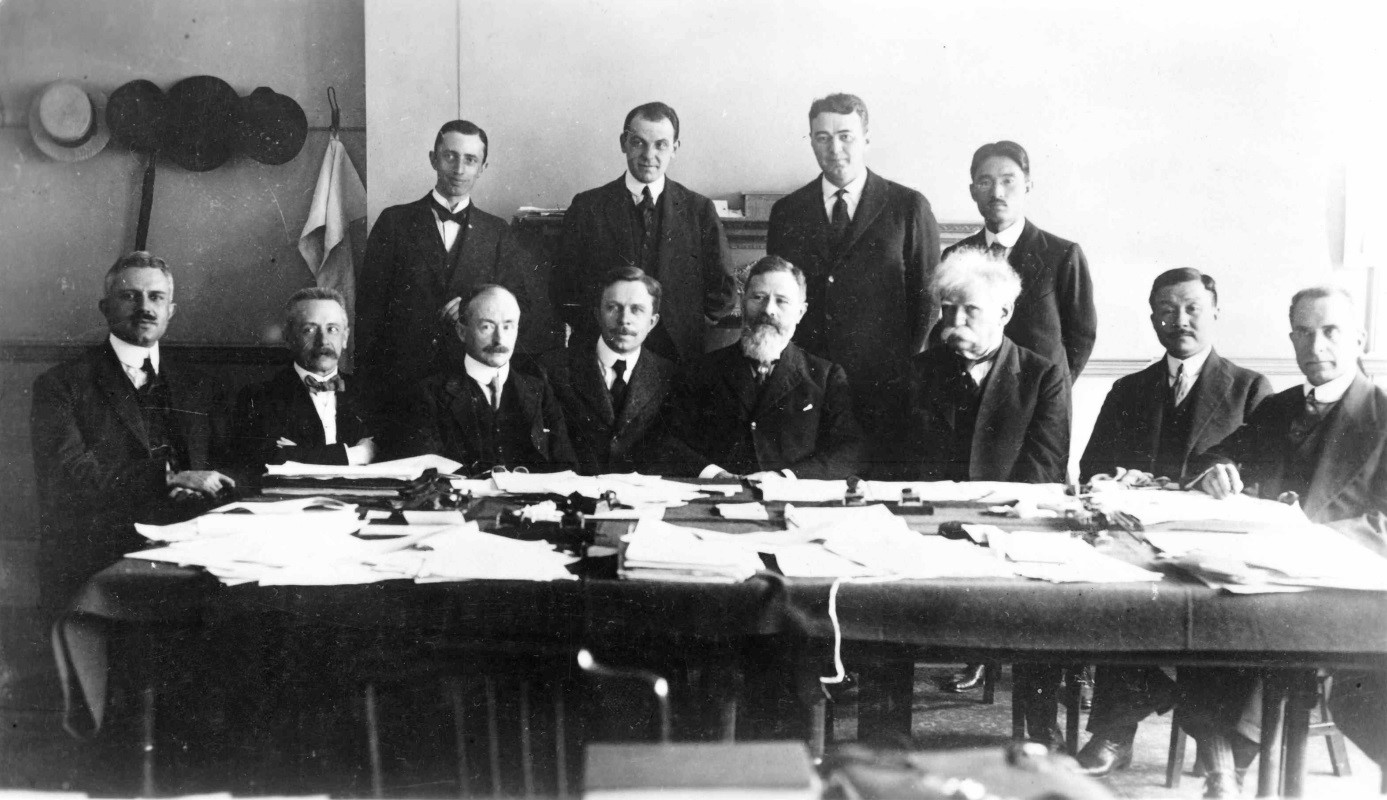

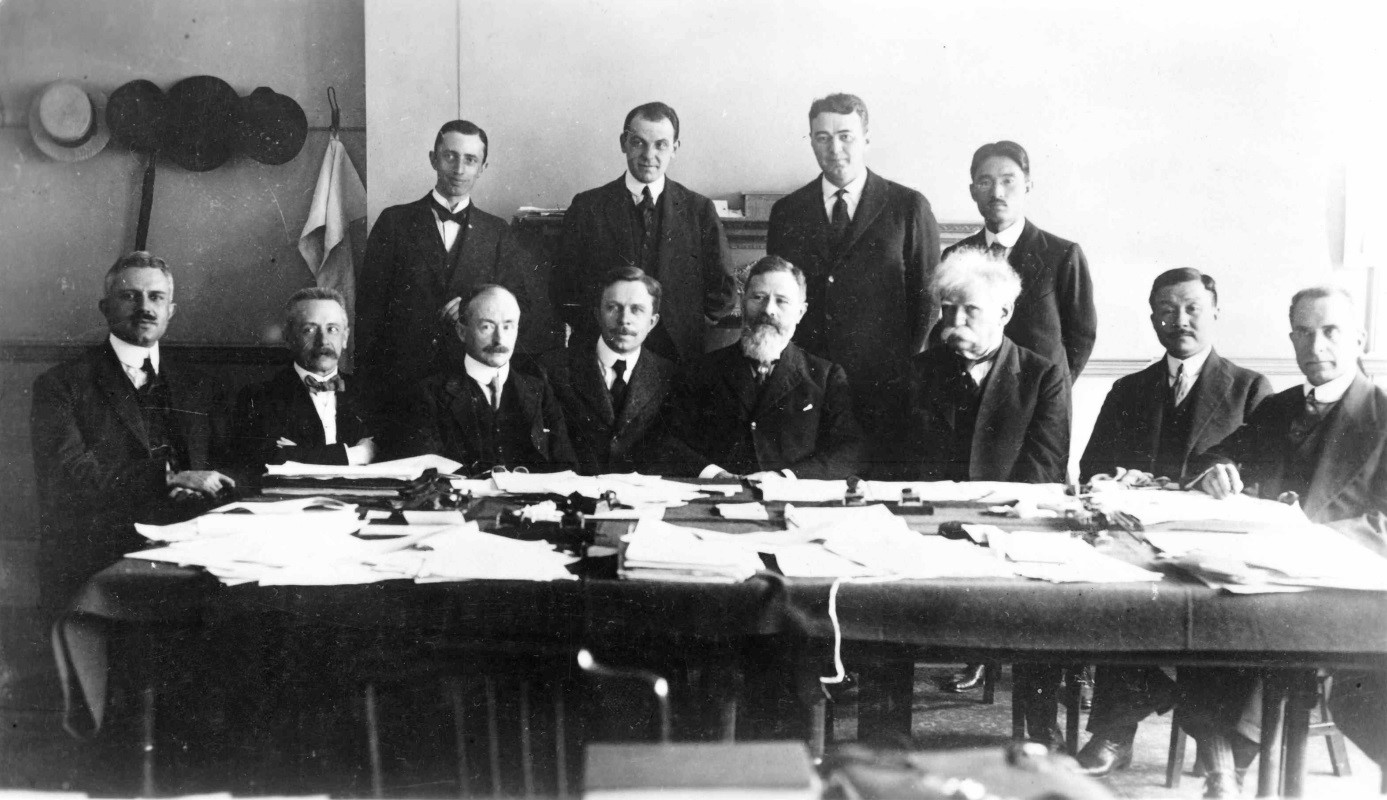

Washington Conference 1919, Organizing Committee: in the center standing, Harold Butler and on his right hand Edward Phelan.

Finally, a word should be said as to the secretarial work of the Conference.

As the International Labour Office was not yet in existence, the secretariat was necessarily recruited in a somewhat haphazard fashion from such elements as were available. Some of its principal members had already acquired some international experience on the staffs of the Commission of the Peace Conference or of the Organizing Committee. Others were borrowed from the embryonic secretariat of the League, while the executive and material arrangements were mainly entrusted to the American personnel recruited on

the spot.

The central feature which distinguishes the secretariat of the Conference from those of previous international conferences is that while the higher officials were all drawn from different nationalities, the secretariat itself was organized not on national but on functional lines.

Naturally, very great difficulties were encountered in organizing a staff recruited at short notice from such heterogeneous elements into an efficient team. Nevertheless, the experience gained at Washington proved conclusively that it was possible to obtain loyal cooperation and a high standard of performance from an international staff.

As the Secretary-General remarked at the end of the Conference, the staff worked with great enthusiasm because they realized that they were assisting in a great movement and had shown by the success which had attended their efforts “that international cooperation may be as successful in the realm of administration as the Conference has shown it to be in the realm of legislation.”

The Governing Body

As will have been already gathered, one of the remarkable features of the Washington Conference was the manner in which it brought to light the major problems inherent in the aims and structure of the International Labour Organization. Not least among these problems was the treatment of the oversea countries. Before the War no extra-European country had taken part in the meetings convened under the auspices of the Association for International Labour Legislation. This was due partly to its purely European origin and inspiration, and partly to the comparatively slight development of industry in oversea countries with the exception of the United States, and even the United States was only beginning to export manufactured articles on a considerable scale. The tremendous demands for war material and the obstacles placed by war conditions in the way of sea transport had deprived the over-sea countries, during five years, of the greater part of the supplies which they had been accustomed to receive from European factories.

During that time many of them had come to develop industries capable of furnishing their own needs, while some of them, such as Japan and Canada, had been stimulated to produce goods for export, either in order to supply the belligerents, whose appetite for munitions of all kinds was practically unlimited, or to capture the over-sea markets, urgently demanding goods which the belligerents were no longer able to offer. In consequence, industrialism had made considerable strides during the War in the over-sea countries, particularly in Asia and America, and many of them had become alive to industrial and social problems, to which they had devoted little attention in the past. It was therefore natural that they should expect to play a larger part in the deliberations of the Conference and to figure more prominently in the principal committees.

During the Conference this issue came prominently to the front on two occasions: the first in connection with the appointment of the Commission to deal with migration, the second in connection with the election of the Governing Body.

The report of the Committee on Unemployment proposed, inter alia, the adoption of a resolution recommending the Governing Body to appoint a Commission to deal with migration problems. Mr. Gemmill, the delegate of the employers of South Africa, moved an amendment on November 25 proposing that “the representation of the States on the European Continent on the Commission should be limited to one half of the total membership of the Commission.” He justified this motion by pointing out that migration was a question that affected both European and oversea countries equally, and that the latter’s interests were consequently quite as much at stake as those of the former. The amendment was eventually carried and represented the first indication of the part which the oversea countries were determined to play in the life of the Organization.

This motion, however, would possibly not have been pressed with so much vigor, had the election of the Governing Body fallen out differently. That election had been announced in the Conference on November 25. It was the result of long discussions and negotiations in the Selection Committee, where the oversea countries had claimed considerably more places than they eventually secured. In the case of the government group, eight of the twelve places available were already assigned by the Treaty to the eight States of chief industrial importance. Among these, Japan and the United States were the only oversea countries included in the list proposed by the Organizing Committee. The Indian Delegation therefore protested, claiming that India was entitled to inclusion as of right in the list, and their first delegate, Mr. Louis Kershaw, declined to take part in the election until the Council of the League had pronounced on the Indian objection. There remained four governments to be elected by the government delegates present at the Conference, with the exception of those representing the eight States chief industrial importance. This election resulted in Argentina, Canada, Poland, and Spain being chosen to fill the vacant places. It was also recommended that in the event of a vacancy occurring Denmark should take the vacant place, a proviso intended to meet the situation which would arise if the United States did not ratify the Treaty.

Thus, four out of the twelve government seats were filled by oversea representatives in the first instance. At a later date, when the Council of the League drew up an official list of the eight States of chief industrial importance, it included not only India but also Canada, a fact which lent some color to the sense of ill-treatment which was prevalent among the oversea delegates at Washington.

Although attempts had been made to secure a measure of oversea representation in the employers’ group, that group in fact nominated six European representatives, while the workers’ group, which disclaimed nationality as a basis for selection at all, appointed five Europeans and one Canadian to represent it in the Governing Body.

The first meeting of the Governing Body, which was held on 27-28 November 1919, therefore comprised twenty European members out of twenty-four. This result provoked a vigorous protest from the oversea delegates, which was finally crystallized in the form of a resolution presented by Mr. Gemmill and supported by a large number of over-sea delegates, expressing “its disapproval of the composition of the Governing Body of the International Labour Office inasmuch as no less than 20 of the 24 members of that body are representatives of European- countries.” Arthur Fontaine on the other hand claimed that the title of countries to membership of the Governing Body should be determined not by considerations of geographical distribution, but by their industrial development and experience, and by the importance of their industrial interests.

When the question was put to the vote, the Conference was very evenly divided. Mr. Gemmill’s motion was adopted by forty-four votes to thirty-nine, the majority being composed of thirty-five oversea delegates, including the workers’ delegates from Guatemala, India, Japan, Peru, and South Africa, together with nine European votes. The minority consisted, with one exception, of European delegates, but most of the workers’ delegates and a number of other delegates abstained from voting.

Moreover, Mr. Gemmill’s initiative at Washington proved to be the starting point for an amendment of Article 393 of the Treaty itself in order to give better representation to the oversea countries.

Nevertheless, despite the differences which had arisen in connection with the distribution of seats, the Conference proceeded to constitute the Governing Body, which thereupon sat for the first time at Washington. This was a step of immense importance in initiating the work of the Organization. It was felt, particularly by the workers’ group, to be imperative that the International Labour Office should be created as soon as possible, if the continuity and development of the work of the Conference was to be assured. The Office could not be created, however, until a Director was appointed, and the Director could only be appointed by the Governing Body. There is no doubt that the view taken by the workers’ group was both sound in itself and justified in the event. When it met for the first time in November 27, the Governing Body elected Mr. Arthur Fontaine as its first Chairman, and Mr. Albert Thomas as provisional Director of the Office. By these two decisions, which were announced on the last day but one of the Conference, the future of the Organization was, as it proved to be, amply assured. Mr. Fontaine’s appointment as Chairman was clearly indicated by his preeminent services at the Piece Conference as Chairman of the Organizing Committee, and as a delegate to the Conference, and for more than eleven years he guided the Governing Body on its way with unsurpassed ability and judgment.

Those who did not already know Mr. Albert Thomas’s brilliant qualities and forceful personality were quickly convinced on acquaintance with him that in his hands the Office would become a great instrument fitted to play the part assigned to it by the authors of the Treaty. Here again, the Washington Conference laid well and truly the foundations of the Organization.

The Achievement of the Conference

In assessing the achievement of the Washington Conference after an interval of thirteen years, one cannot but be struck by the sharpness with which it brought into relief the principal problems which have since been in the forefront of the preoccupations of the International Labour Organization. One is also struck by the vigor and directness with which the Conference proceeded to attack all of these problems and by the progress which it accomplished in preparing, in the short space of five weeks, the groundwork for their solution. It has moreover to be remembered that the constitutional and political issues which have been the subject of this chapter did not constitute the main work of the Conference. The greater part of its time was devoted to drawing up six conventions dealing with hours of work in industry, unemployment, the night work of women, the night work of young persons, the age of admission of children to industrial employment, and the employment of women before and after childbirth. In addition to these conventions, it adopted a series of no less than six recommendations and eight resolutions on aspects of the questions on the Agenda which were not thought suitable for treatment in the Conventions.

At the same time enthusiasm alone could not have enabled the Conference to deal with so large an Agenda. The careful planning of the authors of Part XIII of the Treaty and of the Organizing Committee must also be given a large share of the credit. They had devised a procedure inspired by a real understanding of the conditions necessary to success in international conferences. In the first place, the thoroughness with which the preparatory work was carried out alone made it possible to bring the discussion of the six main points on the Agenda to positive conclusions. The reports presented by the Organizing Committee enabled the delegates to appreciate from the start the extent to which general agreement already prevailed and thus to concentrate on the points which required detailed negotiation and compromise. As a result, the six Draft Conventions, which really laid the foundations of a code of international Labour legislation, were not only duly voted, but were subsequently ratified and put into effect to an extent which shows that they were sound and workmanlike documents. Every international conference since the War has illustrated the lesson that success depends largely upon the care and foresight with which the preliminary work is carried out and that without that indispensable condition failure is almost inevitable.

Indeed, the methods of procedure so successfully applied at Washington furnished a model on which later conferences held under the auspices of the International Labour Organization have operated. It may even be suggested without exaggeration that the degree of achievement of other international conferences has varied largely with the extent to which they followed or ignored the same methods. There is a technique of international discussion, which has to be learnt and which has to be applied by those who understand it. One of the merits of the Washington Conference is that it made a considerable contribution to the formation of such a technique. But good technique, essential though it was, would not by itself have enabled it to solve the many and various problems before it.

A Conference imbued with a lesser faith might well have shrunk from confronting so boldly some of the difficult problems about which decisions were reached at Washington. It might even have hesitated to take any action at all toward setting the permanent machinery of the Organization in motion, in view of the doubt as to the legal validity of the decisions of the Conference which brooded over its deliberations from the beginning to the end. The American Government had emphasized the view that the Conference could have no legality in as much as the Treaty was not in operation. Indeed, Secretary Wilson had explained his final acceptance of the chairmanship on the ground that the Conference could have nothing but an unofficial character, and in his opening address he pointed out that the completion of the organization of the Conference could not take place until the League of Nations had been created and that the final technical steps had not yet been taken, although the creation of the League was then an assured fact. Had the Conference been less determined to brush aside all obstacles in the way of launching the first working part of the League of Nations, it might well have been dismayed by these juridical flaws in its mandate.

They were, in fact, twice discussed by the Selection Committee. Finally, the Governing Body recommended a solution proposed by Mr. Fontaine, which had the merit of being both simple and comprehensive, namely, that the Conference should, as proposed by the Organizing Committee, proceed in accordance with the provisions of the Treaty as if it were legally constituted, and should leave it to the discretion of the Governing Body to take any steps that might be necessary to make its decisions legally effective when the Treaty of Peace came into operation, the Governing Body accordingly being free to reconvene it or to declare it closed as it might think fit. This proposal commended itself to the Conference, which adopted it by the adequate majority of 73 votes to six.

The Governing Body, when it assembled at its second session in January 1920, experienced no great difficulty in cutting the legal knot. The legal adviser to the Conference had maintained the view that the Governing Body required to take no action. When the Governing Body met on January 26, 1920, it would be sufficient if it was considered that the Governing Body, in virtue of the authority delegated to it by the Conference, declared the Washington Session of the Conference closed. This course was accordingly recommended by the Director [Albert Thomas] to the Governing Body, when it met, was adopted unanimously without any prolonged discussion, and was duly notified to the States Members.

All the constitutional obstacles which barred the path of the Washington Conference were thus successfully surmounted. They could scarcely have been overcome, had not there existed a strong determination in all its component sections to achieve success at any cost, and to translate the provisions of Part XIII of the Treaty into a living reality without delay. That is perhaps the outstanding achievement of the Washington Conference, which gives it a special place in the history of the International Labour Organization, and which gives it something of the character of a constituent assembly.

Note:

1 The choice of French and English as official languages was contested at the 1919 Conference. Out of the 36 State Members present, 16 were Spanish speaking. Also the supporters of German voiced their claim, the political bias from wartime was at first a barrier. In the end in 1927 it was decided to adopt Spanish and German as languages of the ILC. (IE)

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO