ILO field offices: coping with political change, civil strife and coups d’état The sub-regional office for the South Pacific in 1987 / Sally Christine Cornwell, Mary Johnson

Category : Centenary - Testimonials

During the ILO’s 100 year history many ILO field offices have witnessed sudden changes of governments – many by force, others by unexpected swings in electoral majorities. Representing the ILO in such situations has posed specific dilemmas for the ILO staff as they have striven to maintain a functional office worthy of the ILO’s highest principles.

This short account highlights the main issues the ILO Office in Suva faced from late 1986 to late 1987. This period included a surprising election victory by an opposition labour political party, followed by a military coup d’etat, a period of conciliation and finally a more definitive and harsher coup d’etat.

Suva: a hub for programmes in the South Pacific

In 1986/87 the ILO had three Member states (Fiji, Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea) and a very large and diversified technical cooperation programme, spread across the South Pacific in more than 12 other smaller island states. The geographical expanse was daunting. Programmes ranged from rural development, vocational training in basic trades, women’s rights and incomes, hotel and tourism management, occupational safety and health in forestry, population and development, workers’ education, maritime training and labour intensive employment techniques to shorter consultancies on enterprise development, employment policies, social security policies and advice on international labour standards.

Support from the ILO Office in Suva to these programmes depended heavily on reliable and regular means of communication and travel over the vast distances between Fiji and the island states, covering approximately one-third of the “watery” globe. The challenges were somewhat unique: it was a time before fax machines became widely available; before the internet and before full access to direct dial phone systems; and the number of airlines was limited, not to mention the frequency of flights. The means that were available (phones through a central Suva exchange, telex messages and wire transfers of funds and scheduled flights) were critical for liaising with the tripartite partners and ILO expert staff outside of Fiji.

Fiji: A balancing act

Each of the South Pacific island states has its own history, cultural identity and political and economic systems. However, because the ILO Office for the South Pacific was (and is) based in Fiji, ILO staff was particularly attentive to the history, ethnic diversity and special measures of governance in the country. The population is composed of a mix of indigenous Fijian peoples, other Pacific Islanders, Indian descendants of indentured workers to harvest crops and Chinese and European descendants of early settlers. Upon obtaining independence from the UK, laws regulating land ownership as well as the Constitution were carefully crafted to protect the rights of the different groups and to ensure harmony. It was more or less a successful balancing act, until 1987.

Political winds unsettle the ILO Office

For many years prior to the 1986/87 period, the Alliance Party, with indigenous Fijian leadership, held the reins of government. Relations with the ILO were excellent, dating back to the ILO Office opening in 1975.

In the early 1980s two developments cast a cloud over the relations between the ILO Office and the Fiji Government. One concerned the use of community labour in Fijian village life, which was viewed by the opposition party of the day as not respecting the ILO’s Forced Labour Conventions. This, in turn, led the Fijian nationalist members of the Alliance Party (the Taukei) to consider denouncing the Convention. The second development was the grave concern of the government that the ILO’s workers’ education project was being used to strengthen the Labour Party. In early 1986 the ILO Office in Suva was requested to close the project unless it could exercise tighter control over the trade union activities. The strain in relations was grave enough that an ILO Deputy Director General from Headquarters undertook a mission to Suva and had extensive discussions with the Prime Minister and the Minister of Labour, as well as with the employers’ and workers’ organisations. This calmed the atmosphere for a time.

In late 1986, surprisingly the ethnically mixed Fiji Labour Party, a coaltion of the Labour Party and the Indo-Fijian National Federation Party, won a majority in Parliamentary elections.

The Governor-General swore in the new government a few months later in the first quarter of 1987. The new Prime Minister was an ethnic Fijian and founder of the Fiji Labour Party. The ceremonial speeches specifically highlighted the important role that the ILO had played in Fiji, citing international labour standards and development cooperation. The Director of the ILO Office was present and received a friendly jab in the ribs from the UNDP Resident Coordinator with a comment that the ILO was all set.

Within a week of the new government assuming office, the new Minister of Finance, a trade union leader of Indian descent and key figure in the Labour Party, convoked the ILO to his office. He requested the ILO act very quickly to obtain funding to launch projects in employment creation and enterprise development. Time was of the essence.

Up until 12 May 1987, the ILO Office in Suva was riding high.

The coups d’etat

On 13 May Lt. Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka led a coup d’etat. He followed a text book pattern, and it was said that his dissertation on graduating from the Australian military college Duntroon had been on models of coups d’etat. The Labour Party parliamentarians were rounded up and locked up as were other trade unionists. Radio and telecommunications were taken over by the military. Airlines and shipping were disrupted, key suppliers and industries were put on hold.

Roadblocks and curfews kept the population subdued.

Tension remained high for the next several months while the different national political entities and the Governor General sought to find some acceptable compromises and solutions. Restrictions remained, but the curfew was eased and travel was possible. However the conciliation efforts failed. In September 1987, a second military coup took place, this time with much harsher measures, including strict curfews, imprisonment of trade unionists and other activists and journalists. The UN Resident Coordinator set up a security committee and declared an emergency situation, limiting UN related travel to Fiji.

The impact on the economy was devastating over the next several months. Tourism declined. In the absence of trust and the rule of law, businesses closed and qualified people starting leaving the country. In short order the Constitution was revoked and Fiji left the Commonwealth. Some embassies withdrew their ambassadors and High Commissioners were replaced.

Dilemmas for the ILO Office

From the first coup d‘état through the months following the second one, the ILO Office in Suva faced a number of dilemmas. The immediate concern was security: for international technical experts, spread around the Pacific; for local technical cooperation staff; and for local office staff who were from different ethnic groups. Communications with the Regional Office and Headquarters, within Fiji and with the other island states constituted a second dilemma as the normal means had been cut off or were carefully monitored. Another concern was how to obtain information about the political situation and the safety of ILO social partners and how to defend ILO fundamental principles in this hostile environment. Finally within the Office every effort was made to avoid political discussions, but it quickly became apparent that staff of Indian origin felt it was better to migrate. In the months that followed there was considerable staff turnover and it was difficult to maintain an ethnic balance in recruitment.

We found a few solutions for some of these dilemmas. Immediately after the first coup, the ILO Office benefited from the satellite communications facilities of foreign embassies to send messages to HQ and the Regional Office. It was a delicate decision as we strived to maintain our international status and tripartite character.

As it was not fair to ask local staff to carry out tasks that might put them in jeopardy, driving to the airport through the roadblocks became a job for an associate expert brandishing her laissez passer with the ILO flag flying on our cumbersome Toyota Crown. Telephoning, typing and transmitting certain telexes, using languages other than English devolved to senior management. The important contacts we had developed with the social partners were difficult to maintain during office hours and equally difficult during the evening curfew, but by walking across gardens and through hedges after sunset to people’s homes, we stayed in touch and were given information on their well- being. During peaceful periods even golf course encounters provided useful information on political developments.

The UN Security Committee was responsible for advising and guiding UN staff should an emergency arise. There was constant tension in this committee around the definition of what action could be taken that would not aggravate the military government. The ILO decided for its own part that when we heard through our good contacts that there could be some civil unrest in the city, we would send our office staff home in the big white van left to our use by the recently completed regional trade union project. We would ring up UNDP to inform them we were closing the office and offer any of their staff a ride home in our van. We became very glad to have that van!

This was a very sad time for all of us who loved the islands and their peoples. With the two coups d’etats something very serious had been broken. Many expectations were crushed and life in the Pacific was changed dramatically and for a long time.* At a certain point after the coup, the Director and deputy Director of the ILO Office in Suva were invited to meet the by now Brigadier General running the country, Sitiveni Rabuka. He asked us to explain the ILO’s principles and operations. We had to avoid some very rocky ground; trade unionists and feminists were being held in custody, the ICFTU was sending a fact finding mission into Fiji, the implications of tripartism and the application of the ILO standards on forced labour continued to be a source of debate and confusion. We played it straight and left shaking hands.

If one can find a silver lining in this cloud of upheaval it would be that the challenges and crises brought us together as ILO colleagues. We formed strong friendships that have lasted to this day. A reunion in Fiji among some of us in the office at that time, including the international and national staff, is being planned.

June, 2018 Sally Christine Cornwell, Mary Johnson

____________

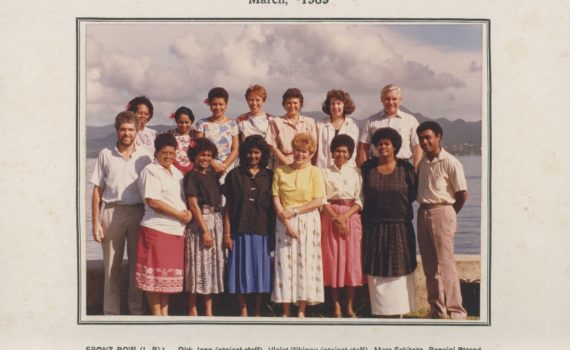

* Political uncertainty reigned for a number of ears after the two coups d’état in 1987. Enough calm was restored to enable the ILO to continue its work during that time. The attached photograph of the ILO Suva staff was taken in 1989. History repeated itself, however, several years later when another coup d’état took place in 2000, again replacing an elected government headed by a multiracial coalition. The 2000-2006 period was highly unstable leading to yet another coup in 2006. A constitutional crisis occurred in 2009 resulting in another abrupt take-over of power. After being suspended for several years, parliamentary elections were held in 2014. The current Prime Minister, who had been instrumental in the 2006 coup d’état, was elected at that time.

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO