Aimée Morel Rommel’s reminiscences fall in two parts: the first recalling the period 1916-1920 when she worked for Albert Thomas prior to his appointment as Director of the ILO; the second dealing with the years as an ILO official at Paris Branch Office from 1920 to the end of the War.

In April 1916, I received from the Sophie-Germain School where I had completed my studies in the “Government Services” section a letter by pneumatic tube requesting me to report to the Under-Secretariat of State for Artillery and Munitions, at the Claridge Hotel, Avenue des Champs-Elysées; the secretariat of the deputy-chief of the Minister’s Office, where there was a former student of the School, needed reinforcing.

I went there immediately. I was received by the deputy-chief, Mario Roques1, and hired that same afternoon.

I was aged 182, totally inexperienced, had never used a telephone, and was coming into the midst of graduates of the Ecole Normale Supérieure: Mario Roques, a professor at the Sorbonne, Albert Thomas, the Under-Secretary of State, socialist deputy for the 2nd district of the Seine, François Simiand, economist and sociologist, librarian of the Ministry of Commerce.

I was to discover that the three formed a solid team, united by friendship, education and political opinions. The Minister’s Office also included Henri Hubert, ethnographer, curator of the St. Germain-en-Laye Museum, Henri Marais, actuary, Maurice Halbwachs, economist, all graduates of the Ecole Normale Supérieure, as well as William Onalid, professor at the Law Faculty and colleague of François Simiand, Charles Dulot, Head of the Press Service, responsible in peacetime for the social column of the newspaper Le Temps, Mr. Sevin for the Manpower Services, Mr. Léon Eyrolles, Head of the Industrial Service, director of the Special School for Public Works, Mr. Jules-Louis Breton, head of the Service for Inventions.

Frequently to be seen as well was Pierre Comert, journalist, graduate of the Ecole Normale Supérieure, as was Paul Mantoux, professor at London University, currently interpreter for Lloyd George, British Minister for Munitions, whom he accompanied whenever he travelled and particularly to the Inter-Allied Committee meetings in Paris. For technical services, the Directorates of the Ministry were headed by general officers of the armed forces.

We had a great deal of work, a day secretariat and a night secretariat; we worked during the week on Sundays and on holidays. That’s war for you, the three-man team gave up all normal private life; Albert Thomas, who lived in his district at Champigny-s/Marne, had a room in the Ministry. My first letter was a request for diplomatic passports addressed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on behalf of the Under-Secretary of State and several collaborators. The Government was sending Albert Thomas and René Viviani on mission to Russia to attempt to obtain from the Czar and the Russian leaders the launching of an offensive to relieve the western front.

Albert Thomas, who had become Minister for Armaments, was to return to that country in April 1917, at the time of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of Kerensky, a period of great upheaval.The secretariat of the Ministry was ensured by that of François Simiand, while the secretariat of Mario Roques provided backup if necessary.

Thus, one day I had to take dictation from the Minister. Great emotion. He dictated fast and at length but the kindly expression on his face more or less reassured me and everything went well.

After every journey, every important conversation, every committee meeting, every visit to General Headquarters (Grand Quartier Général, GQG), the Minister dictated his instructions to the directors immediately, but above all his thoughts, impressions, explanations and suggestions for his two friends, François Simiand and Mario Roques.

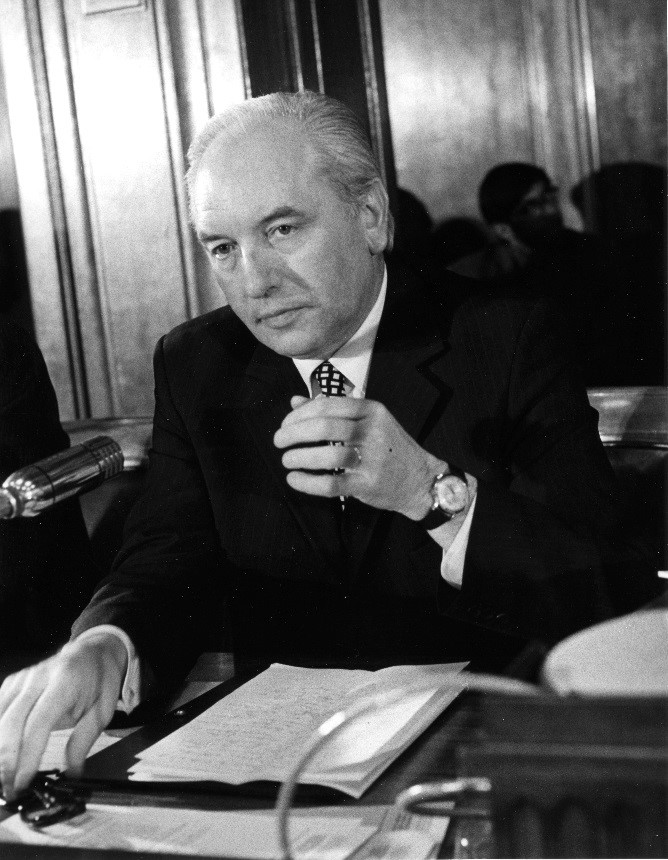

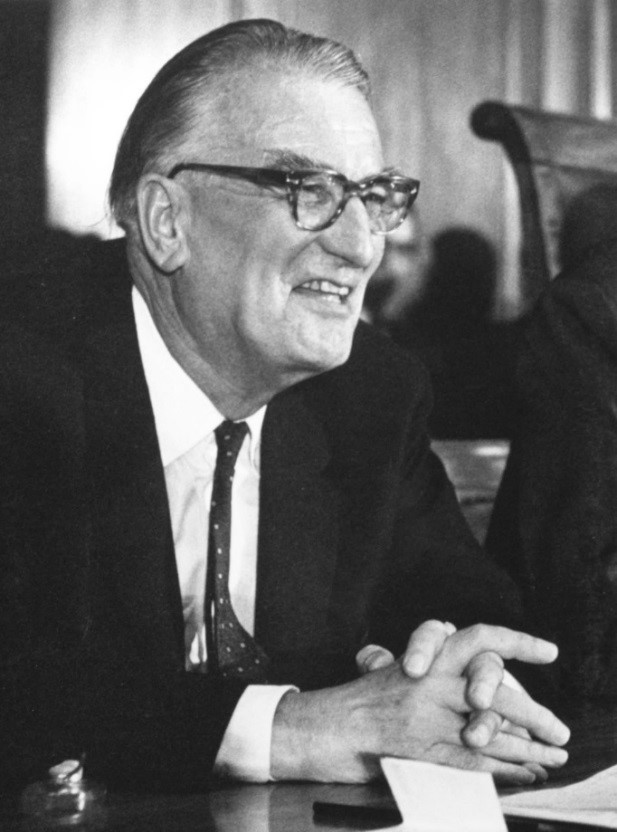

The young Albert Thomas

In the National Archives, in the Albert Thomas Collection assembled by Georges Bourgin, there must be a large number of files containing copies of all these notes; they reflect the Minister’s very life, the permanent impetus provided by the Minister.

Better informed, I learned later that Albert Thomas had been first in everything, prize-winner in the General Competitive Examination when he was a student at the Michelet secondary school, first in the entrance examination for the Ecole Normale Supérieure, first in the State examination for teaching posts in history. He had preferred contact with people, above all the working class, to a teaching career. A militant trade unionist and co-operator, elected member of the municipal council at Champigny in May 1904, then deputy for the Seine in 1910, he was a member of the socialist group in the Chamber of Deputies, that of Jaurès, and immediately compelled recognition by the clarity of his interventions and his precise knowledge of issues.

War broke out on 2 August 1914. The Socialist Party, which had always refused to vote in favour of military credits, accepted to take part in the Government. As early as September, it made Albert Thomas responsible for coordinating the railroads, between the Chiefs of Staff and the Public Works Ministry. An urgent and important task: the north of France, wealthy and heavily industrialized, was being invaded, and munitions as well as men had to get to a broad front at whatever cost.

The efficiency of the young parliamentarian was such that in October 1914, Alexandre Millerand, Minister of Defence, requested him to organize the production of war material. The stocks of the arsenals were absurdly low considering the amounts being consumed at the front. The war was obviously going to be long and the whole of French industry needed to be reorganized. Albert Thomas travelled all over France, visiting manufacturers in order to convince them and to familiarize himself with their problems. The GQG could count on 13,500 shells daily; he demanded 100,000. Manpower was lacking: qualified workers were called back from the front and female labour was utilized; later, workers were recruited in the colonies.

In May 1915, Albert Thomas became Under-Secretary of State for Artillery and Munitions; hence he had access to the Cabinet, to inter-allied meetings and had a whole technical and administrative organization at his disposal. The solid trio came into being. First, François Simiand, company sergeant-major of the territorial army, was assigned to the Under-Secretariat; shortly thereafter, Mario Roques, a volunteer in August 1914, was recalled from the front for the Minister’s Office. Intense work commenced. At the end of 1916, Albert Thomas became Minister of Munitions in the second war cabinet of Aristide Briand, but nothing changed in the cooperation he received, with never a minute of respite, from François Simiand and Mario Roques.

Two sides therefore, one technical and the other social.

The technical side was the responsibility of the large Directorates, which the Minister constantly encouraged and inspired. The results achieved were attested by graphs in the registers kept up to date by the relevant specialized service (registers which should be available either in the National Archives in the Albert Thomas Collection, or in the War Library (Bibliothèque du Service Historique de l’Armée de Terre) at the Château de Vincennes, where official documents are deposited). Requests to the GQG were satisfied with increasing rapidity; he no longer had to go begging.

This branch, however, of the Ministry’s activity was the responsibility of François Simiand and I have only an imprecise memory of it. I must, however, recall the name of a young engineer in the Industrial Service of the Minister’s Office: his name was Hugoniot. Léon Eyrolles had insisted on having him in his Service. Remarkably intelligent, full of imagination and get-up-and-go, Hugoniot had quickly understood that this murderous war required an enormous amount of material in order to spare human lives. The directorates dealt mainly with large firms capable of manufacturing in large quantities quickly (which was understandable), but the Minister believed that, given the huge needs, all the industrial capabilities of the country ought to be utilized and, as of the beginning of 1915, Hugoniot, at his request, went to see the small- and medium-sized enterprises; a marvellous animator, his imagination sparked that of others; he advised them and guided them, no technical problem could hold him in check and the small manufacturers had the joy of feeling utilized and useful at the same time.

Towards the middle of this same year 1915 the GQG, which received 700 large-calibre shells every day – the manufacturing limit of the industry at the time -, requested 50,000, “without which the outcome of the war would no doubt be compromised.” François Simiand spoke to Hugoniot about it. The latter was becoming well-acquainted with “his” manufacturers, he knew where he would find men with initiative and daring. Certain factories would need to be enlarged, the equipment sufficiently increased: it was done. He encouraged the Minister to place orders; however, certain manufacturers on whom he had been counting were hesitant and attempted to back out; he insisted, provided directions and suggestions, assured them that they would be assisted with respect to the military authorities and with respect to the suppliers of moulds. In about a week all the orders were accepted and were carried out. Hugoniot thus saved a great number of human lives.

Other examples could be cited. It seemed to me right to speak about him, an obscure but great Frenchman in these reminiscences about Albert Thomas, Minister of Munitions.

Mario Roques was responsible for personnel and manpower questions. The three friends were very familiar with the living conditions of the working class before 1914; they were constantly preoccupied with social projects.

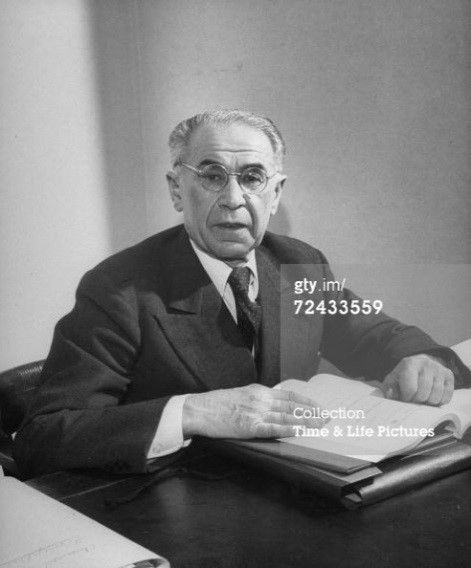

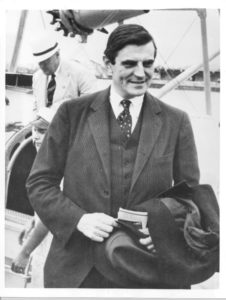

Mario Roques

First of all female labour, indispensable for the production of munitions. On 21 April 1916, a

Committee for Women Workers was created. During more than a year this Committee looked after the organization of women’s work, their recruitment and their employment, as well as the improvement of their material and moral situation.

Then, in a circular of 3 July 1916, it decided to prohibit the employment of women less than 18 years of age for night work in war factories; at the same time the working time for women from 18 to 21 years of age was set at a maximum of 10 hours. It also prohibited the employment of girls aged 16 to 18 in gunpowder factories. On 1 July 1917, another circular established the modalities concerning protection of women workers and extended them to the overall organization of health, safety and medical services in public establishments: it can be said that all the principles of the law on occupational health of 11 October 1946 were set in place.

An advisory labour commission was created with Arthur Fontaine as the effective chairman (who later became the first Chairman of the Governing Body of the ILO, 1919-1931), and with Albert Thomas as its honorary chairman. This was the result of constant consultation with the employers and the trade union organizations. The purpose of this commission was to take all necessary measures to avoid all causes of exhaustion or weakness of the workers employed in war factories, and to seek remedies for overexertion, the main cause of occupational accidents, by advising heads of enterprises to grant periodic rest periods to their workers.

The Minister also concerned himself with the shortage of housing, banned unhealthy dwellings and entrusted the commission with studying the possibility of constructing dormitories close to factories. He brought about the creation of a Cooperative Fund for war factory personnel with a view to solving the problem of feeding workers by creating cooperative supply stores and restaurants.

The manufacturers and workers needed to be kept informed. For this, Charles Dulot, with the assistance of Pierre Hamp, wrote, published and distributed the Bulletin des Usines de Guerre (War Factories Bulletin) a collection of which is housed in the ILO library in Geneva.

I have dwelt on the social activity of the Under-Secretary of State then of the Minister Albert Thomas: was this not a prelude to his role to lead the ILO?

September 1917, ministerial crisis. The Socialist Party refused to participate in the Painlevé Cabinet. Albert Thomas was no longer a Minister, he returned to his seat in the Chambre des Députés. The friends looked to the future. All were of the view that, as a minister, Albert Thomas had built up a capital of social experience and relationships permitting him to play an important role in the new organization of the world which would follow the terrible war. It had to be maintained for him. They decided, each providing his own contribution, to form a group with him in a tiny Association d’Etudes et de Documentations sociales, AEDS (Social Research and Documentation Association), which would cover the costs of an office and a reduced secretariat.

Charles Dulot found a vacant apartment at 74 rue de l’Université; the Socialist deputy was thus installed right in the St Germain suburb, which was very amusing, but vacant lodgings were not numerous. The friends brought along tables and chairs which they each had available at home; a few others were purchased second-hand, a few soft-wood shelves were put up, and work commenced. Arduous surroundings but calm, without jangled nerves, without useless agitation. Along with a colleague, I had abandoned the Ministry in order to follow the minister. As the secretariat was inadequate, voluntary assistance was much appreciated; I remember a retired teacher, the doctor of a social service, a retired primary school inspector, all friends of Albert Thomas; everyone used his ingenuity to make himself useful by looking up documents, research, or correspondence from electors.

The members of the Association visited frequently; once the war was over, Mario Roques returned to teaching at the Sorbonne and came in every day. Conversations were lengthy in the ex-minister’s office.

I remember the emotion felt by the friends on the day they first greeted in this office a comrade who had been a socialist deputy for Alsace in the Reichstag and who had become a Frenchman as a result of the victory over Germany.

As usual, there was a great deal of work to be done, even on Sunday (a day devoted by Albert Thomas to his family), at Champigny where I would go in the afternoon. In this town where he was born and of which he was still the mayor, he never failed to participate each year in the December remembrance day service at the monument for the fallen of 1870. There he loved to meet those who had known him when he was a young schoolboy coming out of his father’s bakery, as well as comrades from the Socialist section. In this familiar milieu, he would express his innermost thoughts on the grave times the country was experiencing and on the problems of the Party.

As a parliamentarian he diligently followed the proceedings of the Chamber of Deputies, where he would take the floor in favour of a just, solid and lasting peace. At the office, he devoted one or two mornings a week to his constituents who arrived in large numbers.

In February 1918, as a Socialist, he participated in the Socialist and Workers Conference meeting in London and he was designated, along with Vandervelde and Henderson, as a member of a commission responsible for requesting that, at the future Peace Conference, each national delegation should include a workers’ representative. He was also present at the 4th Inter-Allied Socialist and Trade Unionist Conference convened on 18 September in London and which was concerned with the introduction of labour legislation clauses in the future Treaty.

As a journalist he contributed to l’Humanité, to the Populaire de Nantes, to La France de Bordeaux and to the Dépêche de Toulouse. Here again he campaigned for the aims of the war which he considered to be just and for a peace based on the right of peoples to self-determination and on the principle of nationalities guaranteed by the establishment of a League of Nations.

In order to put together documentation on social problems, he created with Charles Dulot the weekly publication L’Information ouvrière et sociale of which he wrote the editorials; a collection of these can be found in the ILO library in Geneva.

The articles were sometimes dictated at the last moment, either for lack of time or because they concerned a subject of immediate interest; more than once, because Albert Thomas had to travel that very evening, I accompanied him to the station to allow him to continue dictating in the taxi and on the railway platform, the last sentence coinciding with the train’s departure. It only remained for me to return to the office to transcribe the dictation and then telephone the newspaper to pick it up from the concierge.

As someone involved in the cooperative movement, he had frequent dealings with Ernest Peisson, Secretary General of the National Federation of Consumers’ Cooperatives, whose efforts he supported, particularly through the Committee on Parliamentary Activities composed of senators, deputies and “cooperators”, which met at our office and of which he was the Secretary until 1920. The Federation had material means at its disposal which none of the friends had; occasionally it lent one of its automobiles with a driver to Albert Thomas, a valuable means of gaining time, especially to return home to Champigny.

He also maintained contacts with personalities who came to the Rue de l’Université: Robert Pinot, of the National Council of French Employers, industrialists such as Louis Renault, André Citroën, Marcel Boussac, Dumuis, President Director General of the Iron and Steelworks of Firminy; trade unionists : Léon Jouhaux, Secretary General of the CGT, Merrheim of the Metalworkers, Bidegaray of the Railroadworkers, Delzant of the Glassworkers.

Together with socialists from other countries he created the small Committee of Understanding for Nationalities which included Bénès for the Czechoslovaks along with Serbs, Romanians, and Poles. During the Peace Conference he obstinately defended their cause with the negotiators who were drafting the treaty. With General Rudeanu he took a particular interest in the future of Romania.

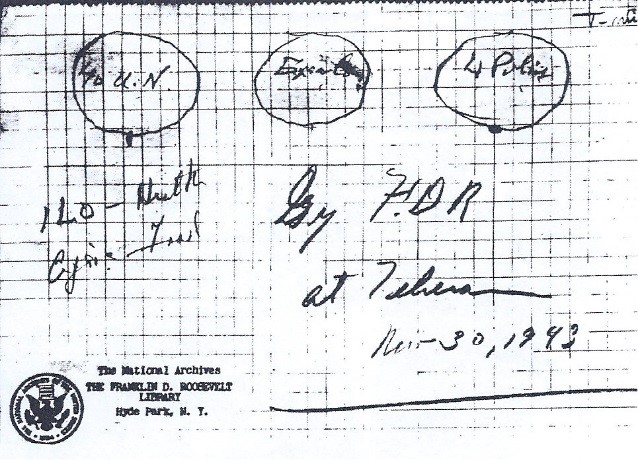

Part XIII of the Treaty of Versailles gave birth to the International Labour Organization. The first International Labour Conference met in Washington in November 1919; governments, employers and workers were represented there. On the unanimous proposal of the workers’ Group3, the candidature of Albert Thomas for the post of Director of the International Labour Office was submitted to the Governing Body designated by the Conference; he was provisionally elected by a secret ballot, 11 votes to 9, and one blank vote.

I was in his office when he was handed the telegram informing him of the results; he was visibly happy, but pensive; perhaps he had an inkling of the enormous and exciting challenge awaiting him if, as he no doubt hoped, his nomination were to be confirmed. When the friends learned the news the same evening, they too were happy as well as proud; it was at the worldwide level that Albert Thomas could henceforth use the amazing resources of his intelligence, of his energy and of his experience in the pursuit of social justice.

His nomination became definitive at the meeting of the Governing Body in Paris on 27 January 1920, and this time the Governing Body ratified it unanimously by acclamation.

Note on the historical context by the Editor.

The nomination of Albert Thomas as the first ILO Director (provisional in November 1919, and definitive in January 1920) was to have an immense impact on the Organization and on the world of labour as a whole. Miss Rommel admired him highly and pays tribute to his vision and his great intellectual and moral qualities.

Readers will no doubt be familiar with Edward Phelan’s fascinating portrait of him in his book Yes and Albert Thomas. Less known but equally important is the opinion of Harold B. Butler, Thomas’ deputy, friend and successor4. “The ILO was fortunate too in securing a leader of exceptional quality. In Albert Thomas, its first Director, it possessed a man of tremendous vision and energy, who regarded himself as the apostle of a new religion. His overflowing personality, his sparkling blue eyes behind his gold-rimmed spectacles, his luxuriant beard, his stocky, vigorous form, and his quick, incisive speech marked him at once as an outstanding-figure. But he was not merely a formidable debater, a tireless worker and a great fighter. He not only had tremendous faith in his mission and inexhaustible resource in executing it. In addition, he was an extremely warm-hearted human person, a brilliant and witty talker, as good a companion at a dinner-table as one could wish to find.

His experience as Minister of Munitions in France and his passionate sympathy with small nations had armed him with a breadth of view and a knowledge of European politics and politicians which he put to full use. By the force of his personality he made for the Director of the Office a position which the Secretary-General of the League was never accorded.

It was the Director’s business to lead. He spoke on every subject and whenever he liked. Whatever the topic of discussion, he was there to represent the international standpoint. Whether in the Conference or in the Governing Body, which corresponded to the Council of the League, Thomas established the tradition that the Office must have a view on every question and express it through the Director. The Director was the repository of the international experience and tradition which the ILO gradually built up, and as such was entitled to be heard.”

Note by the Editor

I have drawn attention to the personality of Albert Thomas because he for Miss Rommel, as for many others, inspired a profound loyalty to the ILO. Her devotion to the Office was shown when she became Officer-in-charge following the death of Fernand Maurette in 1937.

During the German occupation of France she courageously and singlehandedly maintained the activities of the Paris Office, even transferring them to her own small flat when evicted by the enemy.

In the Letter Nr. 29, 2001, based on the official records, I tried to relate this little-known chapter in the history of the ILO. We now have Miss Rommel’s own story giving details not found in the files. Unfortunately, she wrote the description some 30 years after the events at the age of 76 and a certain lack of spontaneity is unavoidable, but she has evidently refreshed her memory by consulting contemporary correspondence. Errors in the original typescript have been silently corrected while misrecollections have been rectified by additional text in square brackets or explanatory footnotes. – The story continues:

Aimée-Elise Rommel

By a stroke of luck the identity card issued in 1939 to Miss Rommel has been found in the ILO Archives, and I am pleased to be able to publish her photograph, the only one we have of her. Further research has also revealed the origin of this manuscript and the reason for Mrs. Morel writing it.

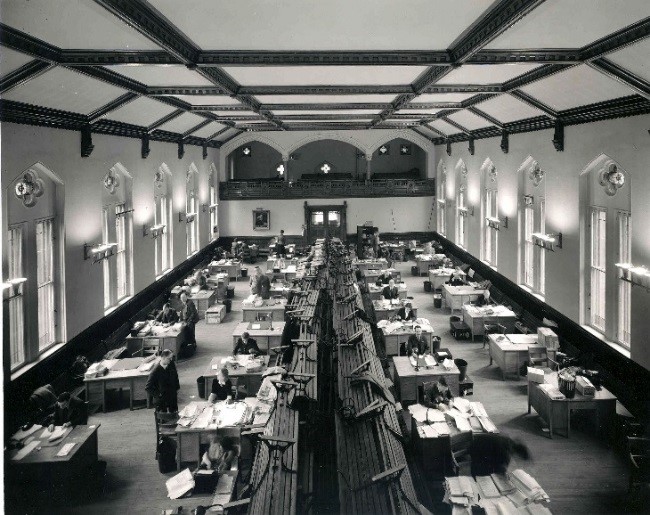

The Paris Office from 1920 and through the War to 1945.

Miss Rommel remembers. The Paris Branch Ofiice5, with Mario Roques as Director, began work at the same time that Albert Thomas became the ILO Director. Thomas had in fact anticipated that he would need a correspondent in the major capitals.

Albert Thomas left for London, which was the provisional headquarters of the International Labour Office. Six months later it was definitively installed in Geneva6. We remained provisionally, for a short time, at the Rue de l’Université and then moved to the right bank of the Seine, 13, Rue de Laborde7. The secretariat was strengthened, the library properly set up. Mario Roques personally concerned himself with its organization. It consisted of course of ILO publications, unique documentation particularly appreciated by the official services, professors, students and journalists. It contained also books and recent periodicals on economic and social questions. But in addition our Director enriched it with rare works on the history of labour that he found in second-hand bookshops or in the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine. The library was used increasingly.

Speaking of the work of the Paris Office under the direction of Mario Roques is difficult because it was varied and complex, which can be seen from several examples. As a professor at the University of Paris, Mario Roques had access to many circles; the fact that he had been deputy of the Cabinet of Albert Thomas during the war further extended his connections and increased his authority.

Contacts with the Government in general and the Ministry of Labour in particular were constant. If an official from Geneva did not come specifically for national or international meetings the ILO had to be represented by the Paris Office. Sometimes ILO commissions held sessions in Paris and it fell to our office to provide for their material organization. The ILO was a recent creation, hence the necessity of meetings for making it known and setting forth its problems.

Albert Thomas came often. More concerned than ever about effectiveness, he saw Government officials and welcomed many. He also had long conversations with his friend Mario Roques, whom he acquainted with his projects and his problems. In 1923, after the first years in operation, he asked him to review in Geneva the whole organization of the ILO; improvements in work techniques were instituted.

On the request of the government Mario Roques was asked to direct the broadcasts of the Radiodiffusion française (which was not yet the O.R.T.F.). He made sure in these programmes that several minutes were reserved every day for social questions. The daily broadcasts were sometimes prepared in Geneva, sometimes in Paris, but information on the ILO was quite austere. Outside collaborators were called on; some of them students of colleagues of Mario Roques are now well known: Claude Lévi-Strauss, the ethnologist, Gaston Bouthoul, the creator of polemology, Francis Raoul who became a préfet, Pierre Paraf of the vivid notes, later the General Secretary of the League against Racism.

From the creation by France of the National Economic Council (first step of the present Economic and Social Council), the Paris office collaborated with it. Mario Roques presented then, among others, a most important report on the large national public works at the time of the employment crisis of 1929-30. The ideas of the report were applied by Geneva at the international level by the text on the fight against unemployment that the ILO would present in 1931 at the Study Commission for the European Union.

On 15 April 1932 we left the Rue de Laborde for 205 Boulevard St-Germain. The document cases were not yet all emptied when Albert Thomas announced his arrival for May 7. We arranged his office. He was extremely tired when he arrived, having made great efforts in Geneva over the previous weeks. His doctors had insisted vigorously that he must res8, but he could not.

He worked on the afternoon of the 7th and [having dined with his old friend Charles Dulot, editor of L’Information Sociale, with whom he had a lively discussion on the French elections] left towards 7 pm. We knew that he crossed the Seine on foot, having met a son of Arthur Fontaine on the Place de la Madeleine, then turned towards the Saint-Lazare railway station, stopped at the Bar of Chez Ruc, near the station. There, he collapsed. The police came9, had him transported to the Beaujon hospital and informed Pierre Waline at the Conseil national du patronat français by telephone and he telephoned Mario Roques.

I heard the news at home on the radio the next morning and went immediately to the office. Mario Roques was there. There was dismay and great sadness. Albert Thomas’ mother, his wife and children came from Geneva. We had to organize the official funeral at the Champigny-s/Marne cemetery, which took place on 11 May. All of Europe, and one could say the whole world, was represented behind the coffin of the man who had devoted all his strength to the betterment of the workers. Important delegations of governments, especially the French Government, of the Council and Secretariat of the League of Nations as well as members of the Governing Body and officials of the ILO were there in large numbers.

Numerous personalities of the political world, the scientific world, the industrial world, were there among the imposing gathering of union activists, socialists, cooperative members, and all the people of Champigny. Many tributes were given.

The ILO, and without doubt the world, had just suffered a great loss, France too, probably, because Albert Thomas seemed to have wished to recover his place in the internal politics of this country fairly soon10. Many had regretted that he had not been at the levers of power during the long discussions at the Peace Conference, in which his clarity of mind could perhaps have avoided some errors. Some friends and qualified collaborators said and wrote as much. A small cog in the wheel of a great life, I see again his large blue intelligent eyes, the expression of goodness in his face, always reflective and always alive. I can evoke the ease and facility of his relationships, his powerful interest in his work and the constant enrichment that resulted. In thinking of the “patron” and the friends who surrounded him, I am grateful for the gift that had been given me over many years of contact with a man of such intellectual and moral qualities.

Mario Roques left the Paris Office at the end of 1936. He was replaced by Fernand Maurette, fellow student and friend of Albert Thomas, with whom he had collaborated in Geneva as an Assistant Director. For us, it was a simple change of personality. The atmosphere of the office was the same, the work techniques were similar. Unfortunately, our new Director died suddenly in 1937 in Geneva where he had gone for the annual Conference11.

International life became more and more difficult, funds came slowly into the international organizations. The Deputy Director under Albert Thomas, Harold B. Butler, who became Director, decided not to replace Fernand Maurette immediately as Director of the Paris Office12; he asked me to insure daily work with my colleague Jean Poirel under the control and with the directives of the French Assistant Director in Geneva, Adrien Tixier13.

Then came the declaration of war in September 1939. Jean Poirel was mobilised; the staff of the Office was reduced to the minimum of four: a secretary, MIle Madeleine Péné; a stenographer, Mme Madeleine Decz (née Duriez); a messenger, Mr. Charles Néel, who was the husband of the concierge, and me. The German advance continued, and I feared bombardment. For the sake of prudence, I had the most important part of the library put in solid cases, carefully covered with waterproof paper, and then taken down to the basement.

Mr. Tixier maintained constant contact by telephone with me and with Mr. Alexandre Parodi, the Director general of Labour at the Ministry of Labour and the French Government delegate to the ILO Governing Body. On 12 and 13 June 1940, the officials of the ministries had to leave Paris14. At the request of Mr. Tixier, Mr. Parodi entrusted me with four mission orders; I closed the apartment, gave the keys to the concierge, and we left with the officials of the Ministry of Labour by military transport. After a bombardment at Rambouillet, we arrived at Indre-et-Loire several days later, and we had to go even further, by train this time. The Bordeaux station was bombarded, and we arrived at Biarritz. I had taken along the accounts and the check books that would allow me, if possible, to obtain from the post office or banking establishments what was needed to ensure our material needs.

The armistice was signed [22 June]. At Biarritz we were in the occupied zone. The French Government officials had to return to their administrations in Paris – as soon as the Loire could be crossed. We followed.

On 12 July 1940, I returned to the Boulevard St-Germain15. The apartment had escaped the requisition of the German army and was intact. I made several phone calls to Paris and let them know that we had re-entered the place and we settled in.

Two ILO publication collections were still on the library shelves. People came to consult them, we even sold some. Some French colleagues, previously in Geneva wrote me from the occupied zone. A portion of the people of the Geneva headquarters, as anticipated, were transferred to Canada, to Montreal. At Geneva only a small group remained under the direction of Henri Gallois, who assured the administration and maintenance. The chief of the Statistics Section, the Englishman James William Nixon, had left for Paris and England too late; he was not able to leave Paris on 14 June, and was arrested16 at his hotel with several compatriots, and they were interned at Fresnes.

On 12 December17, I had a visit from two German officers. The older one asked for news of several French officials from Geneva, among others Camille Pône, Jean Morellet, Louis Dupont. I remained standing and answered that, as he must know, I had no contact with the central office and knew nothing of my colleagues. He informed me that our apartment would be requisitioned, and the rent paid by the Seine préfecture. The German embassy would establish a translator service directed by the young officer with him. He did not see any inconvenience if we four stayed; I didn’t even have to change my office. Before he reached the door I drily asked his name, “because he seemed to know the house so well.” He mumbled a word that began with “Reich”; when he’d left I looked at the personnel list and saw that it was Walter Reichhold, who had been a translator [in the Editorial Service] at the ILO in Geneva, in which section Louis Dupont had also participated as Chief of Service18.

Our occupiers came the next day. The officer, who was the chief of service, took over the room reserved for the Director or for the Geneva officials who came on mission to Paris. The chief translator, Dr Widloecher, was my neighbour in our Director’s office. Two other translators were in the secretariat room, a stenographer and a telephone operator.

Dr. Widloecher asked me to open the safe. It contained only the stubs of old checkbooks. Furious, the German did not press further.

Everything conspired to make our presence useless. When people came to work in the library or to buy some publications, they were told that the ILO no longer existed. I heard Dr. Widloecher give the same response on the telephone, that is, no one gave us the messages for the ILO.

It was evident that this situation could not last. After a conversation outside the office with our former Director, Mario Roques, I went to the Ministry of Labour to see Mlle Henry, the office chief at the Labour Direction, to try to see if my colleagues could be hired by the Ministry. My budget provision was not exhausted but the future worried me.

At the beginning of 1941, Dr. Otto Bach19 visited me, a German whom I knew; he had been our colleague at the ILO Branch Office in Berlin and we had seen him several times in Paris. He toured the apartment and I accompanied him. With astonishment he noticed that the library shelves contained only two collections of ILO publications and some cartons containing notes and files. I explained that, fearing bombardment, the essential part of the library had been sent to Geneva at the declaration of war. Discontented, he left.

Bach directed the German Institute in Paris. On 14 and 21 February 1941, he gave two lectures on the “failure and death of the ILO”. At the same time there began a campaign in the press of the occupation. In Le Matin of 15 February: “Geneva and social justice”; L’Oeuvre of 16 February: “The ILO has closed its doors”; Le Petit Parisien of 17 February: “The ILO is no more”; in Paris-Soir of 19 February: “The ILO closes its doors”; Le Matin of 22 February: “the bankruptcy of Geneva and social justice”; L’Oeuvre of 27 February: “the failure of the ILO of Geneva”; L’Oeuvre of 1 March: “The ILO is dead”.

On 28 February 1941, what I had expected happened. Dr. Widloecher told me that the ILO employees had to leave the office. Nevertheless, the Service wished to keep a stenographer, Mlle Péné, whom he would employ. Her salary would be paid by the Seine Préfecture.

There was in fact a great deal of work and the occupiers made use of outside collaborators. We could see discretely that these people were less than mediocre in quality. Their translations were done in a French that was unworthy of a primary school student.

I went down to telephone M. Roques from a public telephone to ask his advice. He suggested that we accept if Mlle Péné agreed. It seemed to him desirable to keep someone there. I went back to the office, dictated immediately some administrative letters that were necessary so that office expenses could be settled, and at 6 pm I could let Dr. Widloecher know that, except for Mlle Péné, the ILO employees would not return. He protested profusely; he hadn’t meant it to be an order with immediate effect, etc.

I preferred this frank situation, but what would become of Mme Decz and Mr. Néel when my budget provisions were used up? A new approach was made to Mlle Henry, who finally engaged Mme Decz at the Department of Social Insurance. Mme Léonetti, labour inspector, who had been part of the French delegation at several ILO conferences, and who was then in the Cabinet of the Ministry of Labour, admitted Mr. Néel as messenger in her service. Ouf! Only I remained.

Mlle Péné, Mr. Néel and I met one evening a week in a discrete place near the Boulevard St-Germain. Mlle Péné and Mr. Néel told me that the Germans entered the office by the main staircase; they had never requested the key to the service staircase. As people still came to consult or buy ILO publications, Mlle Péné could make small packets which she could hide in a convenient place. Mr. Néel could go up to get them after the departure of the occupiers during the evening or night, and bring them to us.

I approved. Little by little, my studio apartment was furnished with the most frequently requested publications. They were everywhere. To consult or buy them, I received students (a professor of the Law Faculty insisted that the Revue Internationale du Travail be in the room reserved for the candidates for the competitive exam for teaching in the Lycées); government officials (I had given my personal address to Mlle Henry). I met translators of the clandestine publications who came to look for much sought information on countries outside our frontiers for their readers; Louis Saille, the secretary of the C.G.T.; Maurice Harmel, editor of the People, the CGT journal who directed the clandestine Libération; doctors from the Institute of Industrial Hygiene, who were particularly interested in the important reference work Encyclopédie d’Hygiène du Travail, etc.

In spite of the war, the demand for ILO publications grew.

The sales figures :

1941……………. Frs 13,060.90

1942……………. Frs. 48,696.45

1943……………. Frs. 104,226.95

It can be noted that in 1943 the Paris Office (then located at my home) cost only some 62,000 Francs, and the total sales were over 100,000 Francs.

In the middle of 1941 I had the happy surprise of being summoned by an American bank on the Avenue des Champs-Elysées. Geneva, that is M. Henri Gallois, sent some money. He had obstinately sought to re-establish contact and had succeeded.

With small cards printed in advance, the only possibility authorized for the non-occupied zone and foreign countries, I tried to achieve my aim by letting him understand in a brief way my publication needs. One day, a new surprise, I was summoned to the Customs service of the Gare de Lyon. I went. Two packages awaited me from Geneva. The officials told me that since the packages contained printed materials, they had to be submitted to the German censorship; after a few days they would be presented to me if permission was given. If it was refused, I’d be advised.

The packages were delivered to me and many others arrived that were not even censored.

My money problems were completely solved.

I informed our colleague Mr. Nixon20 about our changing fortunes in his various internment camps: Fresnes, Drancy, St-Denis. Two of his friends and I agreed that one of us would visit him every two weeks, on the one authorized day, bringing along some fresh food that we obtained on the black market (those interned received packs of tinned food from the Red Cross). The camp received the war news, even that of the BBC, as much as we did.

I think I must add that at least three of our associates disappeared because of the war: Maurice Harmel died on deportation, as did Dr Hausser, a doctor of the Institute of Industrial Hygiene. Mlle Henry, deported, returned at the liberation, only to die several days after her return.

On 25 August 1944 Paris was liberated. I returned to the Office at the beginning of September, crossing half of Paris on foot; there was no public transport. The office space was again available.

The Deutsche Arbeit Front (the German National Labour Front) had at the end of May removed the last collection of ILO publications and the cartons of documents. The shelves were totally empty. Some chairs were battered and one door was full of bullet holes, a floor tile broken. Even if one adds that in the course of the departure paper supplies were lost and almost all the personal belongings of the four employees, one can conclude that the Office was lucky: lives were preserved; the library holdings hidden in the building’s basement had not been touched; the ILO publications were intact; the funds had been neither diverted nor stolen.

I discovered in Paris that the Deutsche Arbeit Front had not had the time to transport what they had taken to Berlin. Everything was in disarray but in good condition, located at the Comité de l’Amérique Latine, which I had only to have collected as soon as possible. The telephone had been cut, but I was able to have it re-connected with the same number. One could thus re-establish contact.

Mr. Adrien Tixier, the former ILO Assistant Director Minister of the Interior, who together with Alexandre Parodi, the Minister of Labour and Social Security, were members in General de Gaulle’s Liberation Government] asked me to send to Montreal, by the diplomatic pouch of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, an account of the life of the Paris Office since 1940. That was how, by a letter dated 25 October 1944, Mr. Phelan, the Acting Director, was fully informed.21

Mr Adrien Tixier

[In 1945, the first International Labour Conference after the war took place in Paris and was chaired by Alexandre Parodi.] We had only to reconstruct the Office. My three colleagues were reintegrated, new employees were hired, all very young women, intelligent, enthusiastic and full of good will. They had come from the universities and we had to educate them on what the ILO was and how we functioned. They were interested in social questions. With them, normal activity began little by little and the Office once again found a respected place in Paris22.

In July 1963 Mrs. Morel Rommel retired at the age of 65 and died on 15 March 1979.

________________________

Notes:

1 Mario L.G. Roques (1S75-1961). Director of the Paris Branch Office from 17 March 1920 to 3l December 1936.

2 She was born on 28 November 1898 and died on 15 March 1979.

3 By Léon Jouhaux at the 1st Session of the Governing Body, 27 November 1919.

4 Harold B. Butler: The Lost Peace, London 1941, p. 49-50.

5 At the 2nd Session of the Governing Body, 26-28 January 1920, the decision was taken to establish the Paris Branch Office. The contracts of Mario Roques and Aimée-Elise Rommel are dated 1 February 1920.

6 On 8 June 1920 the 4th Session of the Governing Body took the decision to establish the seat of the Office at Geneva, and on 7 July 1920 the staff moved into the building known as La Châtelaine, now occupied by the Red Cross (see my article in the Letter Nr. 26, December 1999, p. 56).

7 13 October 1920.

8 « C’est peut-être alors que furent constatées chez lui des symptômes de diabète et d’urémie » (l’ Information Sociale, Paris 19.5. 1932).

9 “Albert Thomas was unrecognised by the proprietor and staff. The only clue to his identity was his

membership card of the Socialist Party” (Edward Phelan, Yes and Albert Thomas, 2nd Edition 1949, p. 230-231).

10 Others had seen him as a competent successor to Sir Eric Drummond as Secretary-General of the League of Nations (Phelan, op.cit. p.237).

11 He had fallen ill in Geneva and was hospitalized at Clinique Générale where he died on 1 August 1937.

12 For the conflict with the French government regarding the filling of this post, see my article Exit Butler in the Letter, Nr. 28, November 2000, p. 50 ff.

13 lt is significant that his fact and the name of the unsuccessful French candidate, Marius Viple, is not mentioned here.

14 Miss Rommel and Miss Péné departed for Biarritz on Wednesday 12 June and Mrs. Decz and Mr. Néel left for Abilly the following day. The evacuation of staff from the Ministry of Labour had already started on the preceding Sunday.

15 In the words of Miss Rommel: “Paris, devenu semblable à une ville de province le dimanche se repeuple peu à peu” with a curfew imposed from 4 pm to 5 am.

16 On 1 August 1940 at the Family Hotel, rue Cambon.

17 10 December according to other sources. That was also the date when the requisition was signed.

18 In fact Louis Dupont had not been in the same unit as Walter Reichhold but was a translator-reviser in the Legislative Service. Reichhshold was known to have pulled down the picture of Albert Thomas in the Berlin Office and replaced it with one of Adolph Hitler! He resigned on 15 May 1938.

19 Otto Bach has been an official at the Berlin Office.

20 James W. Nixon, chief of the Statistical Section, had been prevented from returning to Geneva and had, as a UK citizen, been interned. By the Germans.

21 Original letter on file p. 14/3. II (LO Archives). Phelan replied with a telegram dated 16 November 1944 in which he congratulates her with her devotion and success in maintaining the activities of the Paris Office during the occupation.

22 Mrs. Morel (as Miss Rommel was now known having married Julien Auguste Morel on 21 December 1944) continued as Officer-in-Charge of

the Paris Branch Office until the appointment by the

new Director-General David A. Morse of Mrs. Augustine Jouhaux as Director of the Paris Branch Office on 1 September 1949

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO