There are two motivations for writing this article. The first is the rapidly approaching centennial of the International Labour Organisation which gives us all the more reason to review its history. Being cognizant of its past can be useful for the ongoing debate about its future. The second is the valuable amount of research on the ILO in recent years. This has included the case of Germany which shows in an “extreme situation” the pathways, mechanisms and limits of the internationalization of social policy.[1]

Clearly, Germany played an ambivalent role in the foundation and the subsequent evolution of the ILO. We witness light and darkness in Germany’s relationship with the organization, ideological convergence and divergence, and periods of association and dissociation.

On the positive side, with its concept of “Sozialstaat”[2] – designed to provide social security, social justice, social integration, and individual freedom for all of its citizens – and owing to its professional competence in the areas of occupational safety and health, labour inspection, labour law and collective bargaining and industrial relations, Germany made a significant contribution to the creation of the ILO and its central ideas, its system of international standards and its technical cooperation programmes. Germany played a pioneering role in social insurance policy. Beginning in 1883, it was first in Europe to adopt compulsory state insurance relating to old age, illness, invalidity, and industrial accidents.[3] Furthermore, Germany assisted in promoting the substantive agenda of the ILO in areas such as vocational education and technical training, occupational rehabilitation and cooperatives.

In 1890, an “International Conference for the Regulation of Work in Industrial Plants and Mines” was held in Berlin. It adopted resolutions on the introduction of minimum working standards in Europe, including minimum age, weekly rest, and the employment of children, young people and women. It has been regarded by some as the birth of international labour law and a forerunner of the ILO.

Since then, German government officials, trade unionists and academics were among the initiators and supporters of the International Association for Labour Legislation (IVGA), which formed the first International Labour Office in Basel in 1901. It is regarded as a precursor to the ILO. In the same year, a national German section of this Association called the “Gesellschaft für Soziale Reform” was set up in Bonn. Later, together with 25 other national affiliations, the German group participated in the activities of the International Association for Social Reform (1924-1933), whose first president was the ILO Director Albert Thomas.[4]

Although industrialization, and along with it the rise of the status of the employee, started later in Germany than in the United Kingdom and Belgium, the country gradually became one of the leading industrial nations in the second half of the 19th century. It developed strong collective organizations of workers and employers. Next to the UK, it had the largest trade union movement in the decades before World War I. German unionists took up leading positions in the international trade union organisations. From 1903 up to WW one, Carl Legien chaired the International Trade Union Secretariat of European and North American unions and its successor organization, the International Trade Union Federation that was set up in 1913. The German trade union movement, and particularly its largest and most influential social democratic, reformist component, aroused the interest of Albert Thomas. As early as 1902, he established contact with the German labour movement when he was a student at the University of Berlin. In 1903, he wrote his doctoral thesis about the German version of socialism.

Structural affinity between the ILO and Germany is perhaps closest when it comes to tripartism as a model of governance. The involvement of representatives of interest groups of workers and employers in decision-making in social and economic policy has a long tradition in Germany. It has taken various forms and names, such as “social partnership”, “social market economy” (after WW II), and “concerted social action” (1967-77, relating to monetary, fiscal and incomes policy). Tripartite social dialogue at the federal, state and local level has been of vital significance in improving the country’s economic and employment performance. For example, during the recent financial crisis starting in 2008, when Germany’s GDP declined more than in most other EU countries, the loss of jobs and the rise of unemployment were marginal. Adjustment was accomplished largely through reducing working hours instead of layoffs. It helped to stabilize aggregate demand. As the costs of adjustment were shared fairly among workers, employers and the government, it facilitated a broad sense of confidence in the economy.[5]

Particularly in the years of the Weimar Republic of Germany (1918-1933), tripartism in the ILO was inspired by the national German practice of the equal participation of workers and employers (parity).[6] However, it is also evident, that the liberal model of tripartite rule which is congruent with ILO principles of freedom of association and independent interest groups has not been consistently applied in Germany. There were periods of authoritarian corporatism in which civil liberties and conflict resolution through negotiation and genuine social dialogue were suppressed and government ordinances put in their place. It happened most of all under Bismarck’s paternalism and the repressive Socialism Act of 1878, in the National Socialist (Nazi) era (1933-1945), and in the German Democratic Republic in east Germany (1949-1990).

In decisive phases of the development of the ILO in the years after World War I, and even more so after World War II, the German state stood largely outside the ILO, and the international community altogether. The nation’s capacity to contribute to institutionalizing international law was severely hampered by its role as aggressor in the two world wars and the chauvinist and racist posture of the Nazi regime that squarely contradicted the pluralistic spirit of the ILO. The formative years of the Organization in the 1920s were dominated by France and the United Kingdom. In addition to them, Belgium, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, Italy, Japan, Poland and the United States were part of the Commission on International Labour Legislation of the Peace Conference in 1919 that negotiated the ILO’s first Constitution. As loser of World War I, and charged with the sole responsibility for this war in the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was excluded from the peace talks. It did not take part in the first International Labour Conference in Washington D.C in 1919 but joined the ILO only later that year, following the decision at the Second Sitting on 30 October to admit Germany and Austria as members.19 Granting it membership was demanded by the representatives of the employers and workers in the ILO and some governments, particularly Belgium. While the former were afraid that Germany with its large export sector might gain unfair advantages in international competition if it was not committed to observe the normative standards of the ILO, the latter requested and justified the integration by pointing to the strength of the German labour movement.[7]

Although Germany was not among founding nations of the ILO, it indirectly exerted political pressure on its inauguration. During and shortly after WW I, social unrest, strikes and revolutionary movements sprang up in Europe and even in North America, starting with the October Revolution in Russia in 1917, and followed by the establishment of temporary soviet republics in Hungary and Northern Italy. In Germany, political uprisings, called the November revolution started on November 4, 1918, when groups of workers in the North joined the navy to call for an overthrow of the government and a new political order in the country. The following day, revolts by workers and soldiers spread to Munich, Berlin, and other big cities, leading to the formation of (short lived) worker republics and the foundation of the communist party. In early 1919, the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George wrote to the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau: “The whole of Europe is filled with the spirit of revolution. There is a deep sense, not only of discontent, but anger and revolt among the workmen, against pre-war conditions. […] The whole existing order in its political, social and economic aspects [is] questioned by the masses of the population from one end of Europe to the other”.[8] Setting up the ILO in this crisis ridden situation may be seen as an attempt by a coalition of the reformist political left and conservative governments to thwart the revolution and stabilize the economic system by securing the loyalty of the labour force trough an international social reform programme.

Despite the marginal role of the German government in the ILO in the inter-war period, the country was not without influence in the Organization during that time, thanks to exchanges and collaboration drawn from institutional, personal and technical relationships. Most important among the links was the ILO Branch Office in Berlin set up in 1921, and closed down in 1934. It was headed by Alexander Schlicke (1921-25) and Wilhelm Donau (1925-34), both social democrats. Both promoted the cause of the ILO in Germany and cooperated closely with the Ministry of Labour for that purpose.[9]

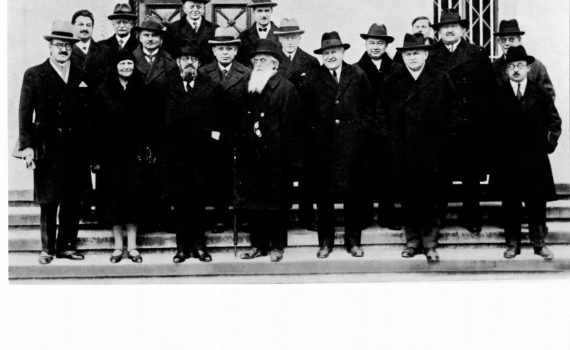

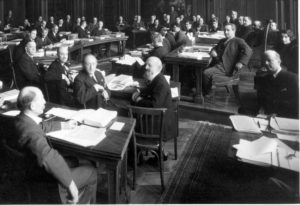

Marius Viple, Albert Thomas ahnd Wilhelm Donau in Berlin

In the early 1920s, some German officials of the ILO, working in Geneva and/or at the Branch Office in Berlin, faced a severe conflict of loyalty. They were torn between their duties as international civil servants and the defence of national interests as German citizens. The conflict intensified between 1923 and 1925, when the officials voiced opposition in public to the hardships suffered by workers in the Ruhr and the Saar districts because of reparations imposed on Germany under the Peace Treaty of Versailles. They thought the ILO was wrong to acquiescide to this situation. According to Sandrine Kott[10], these events contributed to the inclusion of the rule in the Staff Regulations of the ILO which requires from the officials to show exclusive loyalty to the Organization, and not to seek or receive instructions from any national authority in regard to the execution of their duties.[11]

Hitler Germany terminated membership in the League of Nations and the ILO. The withdrawal was declared in November of 1933 and became official in 1935. Yet, the disruption of the links between the Third Reich and the ILO was not as abrupt and complete as one might expect in view of the intolerant and racist complexion of the Nazi regime. It progressed step-by-step along with the imposition of full dictatorship. Among the first casualties of the new regime was freedom of association. The German trade unions were disbanded in May 1933. Their premises were occupied and leading unionists sent to concentration camps. A mandatory organization, called the “German Labour Front” (DAF) replaced them with the sole task of implementing the will of the Nazi government. The employers’ organizations were also banned and merged into the DAF as a way of “overcoming class struggle”. At the International Labour Conference in June 1933, Nazi representatives led by Robert Ley, chief of the DAF, demanded the mandate of the unions. However, the ILC refused to issue credentials to the new “worker delegation”, which then left the Conference. To gain legitimacy and acceptance, the Nazi delegation had tried in vain to win over Wilhelm Leuschner, board member of the German General Trade Union Confederation (ADGB), a social democratic politician -and ADGB delegate to the ILC.

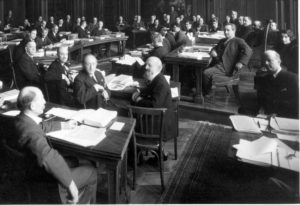

Wilhelm Leuschner at the 61st Session of the Governing Body in June 1933

Because of his refusal to collaborate, Leuschner was arrested immediately after his return from Geneva to Germany. Later, he became part of the German resistance movement. He was sentenced to death and executed in September 1944.[12]

From the point of view of ILC delegates and among some ILO staff members (mainly German), there were divergent attitudes towards the maintenance of relations with Nazi Germany. At least until 1935, the ILO under its Director Harold Butler was willing to make compromises with the new regime. The German government demanded and in fact achieved the dismissal of some German experts and ILO staff members seen as being “unreliable”. To some extent, the conciliatory position of the ILO was related to the social policy stance of the Nazis. It put emphasis on (a contrived version of) social peace, the fight against unemployment, paid vacation, the extension of maternity protection, and the provision of recreational opportunities for workers (“Kraft durch Freude”). Like other fascist regimes in Europe, the Nazis tried, not entirely without success, to legitimize internationally their “superior” welfare policy, export it to other countries, and instrumentalize the ILO for these purposes. It was not until 1941 that the International Labour Office finally condemned the social policy of the Nazis as “totalitarian”.[13] By then, it had become entirely clear that the policy had been put at the service of Germany’s imperial ambitions. In May of 1941, Robert Ley of the German Labour Front tried to get the Swiss authorities to occupy the ILO premises in Geneva.[14] By that point, the Office was already installed in Montreal where it had been relocated in 1940.

West Germany, i.e. the Federal Republic of Germany, re-entered the ILO in 1951. In the presence of Director-General David A. Morse, an ILO Branch Office was established in Bonn and the German Government declared acceptance of the 17 ILO Conventions ratified by Germany before it had left the ILO.[15] The German Democratic Republic in the East joined the ILO in 1973, the same year in which each of the two German states became members of the United Nations. Hence, they were not part of the international community when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was passed in 1948 and the two Covenants in 1966: the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, both containing provisions of importance for international labour standards.

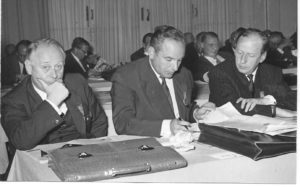

Francis Blanchard with F.G. Seib at a meeting in Germany

After the World War II, the ILO was one of the first international organizations that helped to pave the way for Germany back into the international community. Two eminent French members of the ILO Governing Body were advocating and helping to achieve Germany’s return to the ILO. On the workers’ side, the trade unionist Léon Jouhaux was a driving force behind the reconciliation between the French and German labour forces and Germany’s re-entry into the ILO. Jouhaux held a leading post in the CGT, before he left to establish the Force Ouvrière and became its president in 1947. He was also vice-president of the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1951. On the employers’ side, Pierre Waline, a leading member of the employers organization in France and president of the International Employers’ Organization (IOE) from 1953 intervened in favour of improved relations between France and Germany. He was awarded the German Great Distinguished Services Cross (“Grosses Bundesverdienstkreuz”.[16]

In the second half of the 20th century, Germany’s role in the ILO became much more constructive. With few exceptions, the German government and the German organizations of employers and workers have been among the staunch supporters of the Organization’s core policies, notably on employment and decent work. They played an important role in shaping the policy of the European Union in relation to the ILO. The German federal government made sizeable financial and staff contributions to the technical cooperation activities of the organization. In 1992, it allocated 50 million Deutschmarks to launch the International Programme for the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC), which later on became the largest technical cooperation programme of the Office. Special funding was provided by Germany for ILO projects under the World Employment Programme in Africa, economic and social restructuring in Central and Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and ILO country programmes for decent work. After the United States and Japan, Germany became the largest financial contributor of the organization.

In recent decades, Germany increasingly took part in the governance and leadership of the ILO. Since 1954, it has been a permanent member in the Governing Body. In 1976-77, Winfried Haase from the Federal Government was elected chairman of the GB, the first German in this important post. Gerd Muhr from the German Trade Union Federation was elected chairman of the GB in 1990 and the German government representative, Ambassador Dr Ulrich Seidenberger is chairman of the Body in the present period of 2016-17. The ILO Regional Office for Europe had several German directors. We have not yet seen a German at the helm of the International Labour Office. Presumably because of the heavy responsibility of the nation for the political devastations in the 20th century, the German government has not proposed a national candidate for the post of Director-General so far. Rightly so, I would say, also in view of the disproportionally large number of European citizens who have occupied this position.

To sum up, Germany had its share in the prehistory of the ILO and thereafter. It may be counted as one of the influential reference points for ILO policies and programmes, thanks to its contributions to the emergence and development of international labour legislation, labour inspection and social security policy, and furthermore, the comparatively large and well organized collective organizations of workers and employers and the accommodating relations between them. The concept of tripartism in the governance system of the ILO corresponds to, and has been inspired by, the German tradition of social partnership in labour market and social policy. Nevertheless, Germany was not a leading player in the ILO during the most innovative years of the Organisation, mainly because of the country’s aggresion and defeat in the two world wars and the racism and crimes of the Nazi regime that were incompatible with the universal and humanist orientation of the ILO. Germany was absent from the organization at times when the guiding principles and some of the most important constitutional elements of the organization, including the Declaration of Philadelphia, were adopted. It became a fully committed ILO member in the second half of the 20th century. It has been supportive of the Organization’s policies, generous in its contributions to the technical work of the Office, and largely respectful of inter-national labour standards. Nevertheless, Germany has yet to make considerable efforts to turn the country into a paradise of decent work for all.

[1] Kott, Sandrine : Dynamiques de l’internationalisation: L’Allemagne et l’Organisation internationale du travail (1919-1940), Critique Internationale, 2011/3, No. 52, p. 72

[2] Kott, Sandrine : Der Sozialstaat. In: Deutsche Erinnerungsorte II, Etienne Francois und Hagen Schulze Hrsg., Verlag C.H. Beck, 2009, pp.485-501.

[3] for details, see Kott, 2011/3, op. cit., pp. 78-79; and the chapter on social protection in Rodgers, G. et al, The ILO and the quest for social justice, 1919-2009, ILO, Geneva, 2009, pp. 141-144

[4] Schewe, Dieter : Initiativen und Unterstützung für die Internationale Arbeitsorganisation durch die Gesellschaften für Soziale Reform/Sozialer Fortschritt 1890-1993, in: Weltfriede durch soziale Gerechtigkeit. 75 Jahre Internationale Arbeitsorganisation. Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Sozialordnung, Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Arbeitgeberverbände, Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (Hrsg.), Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden, 1994, p. 37ff

[5] International Institute for Labour Studies : Germany: A Job-Centred Approach, Studies on Growth with Equity, ILO, Geneva, 2011, pp. 2-3 and chapter 8.

[6] Guerin Denis : op.cit., p.31.

19 J.T. Shortwell, The Origins of the International Labour Organisation, 2 vol., New York 1934, I, pp. 260 ff.

[7] Admission de l’Allemagne et de l’Autriche dans l’Organisation permanente du Travail, Genève, BIT, 1920.

[8] quoted in Rees, J. : “In defence of October” in: International Socialism, 52, Autumn 1991, London, p. 9.

[9] Kott, 2011, op. cit., pp. 74-75.

[10] Ibid., p.77.

[11] see Articles 7 of the ILO Staff Regulations, January 1923.

[12] for a detailed account see Tosstorff, Reiner : Workers’ resistance against Nazi Germany at the International Labour Conference 1933, ILO, Geneva 2013.

[13] Kott, 2011, op. cit. p. 82; Waelbroeck, P. and Bessling I. : Some Aspects of Social Policy under the National Socialist Regime, In: International Labour Review, February 1941, pp. 127-152.

[14] for details about the relationship between the ILO and the Nazis, see Kott, 2011, op. cit., pp. 72 and 80-83.

[15] for details see Seib, Friedrich Georg : The ILO Office in Germany, In: MESSAGE no. 34, 2003.

[16] see Erdmann, E.- G. : Deutschlands Mitgliedschaft in der IAO – Ein Reflex seiner Geschichte 1919 – 1933 –

1951, In: Bundesministerium für Arbeit und

Sozialordnung, et. al., op. cit., pp. 28 and 34.

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO

The Section of Former Officials of the ILO

Who can forget the incident when, after a very heavy rainfall, water was dripping from the ceiling near the R.3 delegates bar, a colleague put a huge baking tray (from the ILO kitchen) filled it half way with water and put plastic fish and a lobster in with a caption “Donations to the Fund for the Renovation of the Roof ”. We were working at the time on an umpteenth version of a PFAC paper concerning the renovation work to be done and we still don’t know to this day who took the money or the lobster!

Who can forget the incident when, after a very heavy rainfall, water was dripping from the ceiling near the R.3 delegates bar, a colleague put a huge baking tray (from the ILO kitchen) filled it half way with water and put plastic fish and a lobster in with a caption “Donations to the Fund for the Renovation of the Roof ”. We were working at the time on an umpteenth version of a PFAC paper concerning the renovation work to be done and we still don’t know to this day who took the money or the lobster! The atmosphere was always joyful; by getting to know each other better in a harmonious atmosphere it made for good working relationships in our daily life. The farewell parties included the invitees the retired person wished to have present, but always included the bosses of course not just for the speeches and presents, but out of the mutual respect earned on both sides. It was also a means of thanking colleagues in other branches and departments for their support and assistance over the years because without them the work could not be completed and finalized – a true Team Work to get a job done.

The atmosphere was always joyful; by getting to know each other better in a harmonious atmosphere it made for good working relationships in our daily life. The farewell parties included the invitees the retired person wished to have present, but always included the bosses of course not just for the speeches and presents, but out of the mutual respect earned on both sides. It was also a means of thanking colleagues in other branches and departments for their support and assistance over the years because without them the work could not be completed and finalized – a true Team Work to get a job done.