Ma plus grande réussite en 25 ans de travail à l’OIT : l’identification du délégué cubain à la Commission de la législation internationale du travail !

A l’approche de la retraite, dans les derniers jours de juin 2016, il m’a semblé que je devais distraire mes collègues du Département des normes internationales du travail de l’immense tristesse causée par mon départ par le récit de ce qui me semble avoir été le résultat le plus notable de mon travail, pendant 25 ans, au Bureau international du travail.

Mon exploit le plus important en tant que membre du Bureau a été de rectifier le nom du délégué de la République de Cuba qui figure sur la photo historique de la Commission internationale de législation du travail, prise à Paris, au début de la Conférence de paix, le 25 janvier ou le 1er février 1919, selon les recherches que j’ai effectuées pour élaborer ce texte.

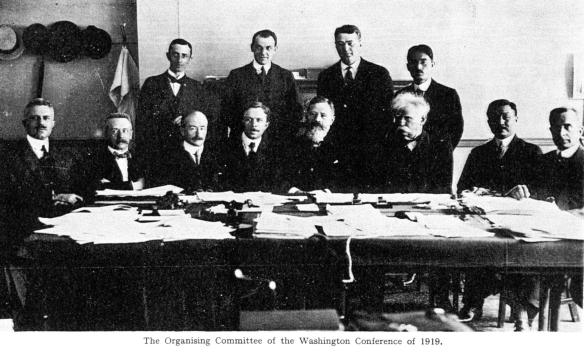

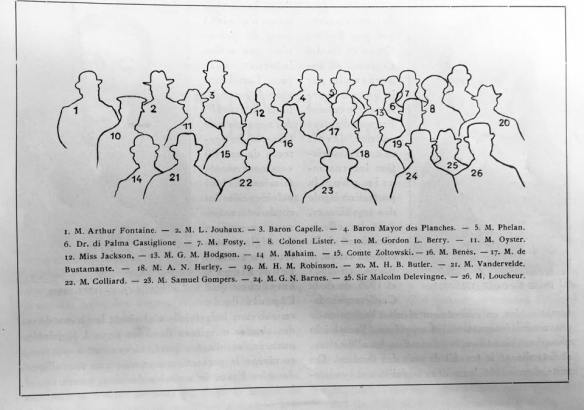

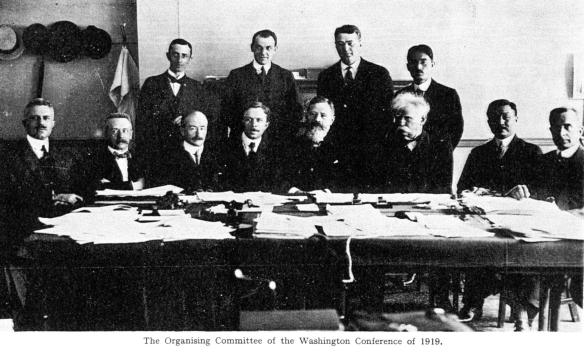

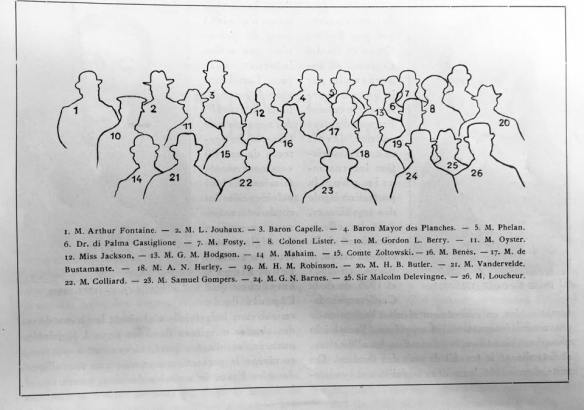

1. A. Fontaine — 2. L. Jouhaux — 3. Baron Capelle — 4. Baron Mayor des Planches — 5. E. Phelan — 6. Dr. G. E. di Palma Castiglione — 7. Fosty — 8. Coronel Lister — 10. Gordon L. Berry — 11. Guy H. Oyster — 12. Mme. Jackson — 13. G. M. Hodgson — 14. E. Mahaim — 15. Comte Zoltowski — 16. E. Benés — 17. Dr. Martínez Ortiz — 18. A. N. Hurley — 19. H. M. Robinson — 20. H. B. Butler — 21. E. Vandervelde — 22. P. Colliard — 23. Samuel Gompers — 24. G. N. Barnes — 25. Sir Malcom Delevingne — 26. L. Loucheur.

Pendant de très nombreuses années, la photo de la Commission de la législation internationale du travail a été exposée, parmi d’autres vestiges des archives du BIT, à proximité de la cafétéria de la salle du Conseil d’administration. Tout ce temps, en buvant les tasses de café au lait et de thé que je consommais quotidiennement pendant mes années en tant que fonctionnaire, je n’ai cessé d’admirer le visage du numéro 17 sur la photo, le seul nom latino-américain, parmi tant de personnalités européennes distinguées. Le nom indiqué pour le numéro 17 était celui de Sánchez de Bustamente. Antonio Sánchez de Bustamente y Sirven (1865-1961), que j’appelle respectueusement Don Antonio, l’éminent auteur du Code de droit international privé, dont j’ai entendu parler à la Faculté de droit de Buenos Aires et qui continue à être étudié dans les bons cours de droit en Amérique.

Les moustaches du chiffre 17 retenaient aussi mon attention, puisque je n’ai jamais réussi à faire pousser sous mon nez une moustache digne de ce panache.

En mars 2016, lorsque j’ai atteint l’âge de la retraite, pendant les trois mois au cours desquels mon contrat avec le Bureau a été prolongé, j’ai été invité à préparer une mission au Panama pour débloquer le processus de ratification de la convention (no 169) relative aux peuples indigènes et tribaux, 1989.

Afin de préparer mes présentations au Panama, et étant donné que tout le monde m’avait demandé à plusieurs reprises pourquoi l’OIT s’occupait des peuples autochtones, j’ai pris le temps d’analyser le texte du Traité de Versailles. Ma belle-mère Jacqueline D. m’avait offert un précieux exemplaire original de ce texte. Ce n’est qu’en touchant les pages jaunies du Traité de paix que l’on comprend que la Société des Nations avait, parmi ses priorités, la promotion des conditions de vie des peuples et des communautés “non encore capables de se diriger eux-mêmes dans les conditions particulièrement difficiles du monde moderne” (article 23, page 34 du texte officiel). L’Organisation du travail devait élaborer des conventions internationales du travail qui peuvent ou non être appliquées dans les colonies (article 421 du Traité de Paix aux pages 421-422 du texte officiel). En conséquence, de 1935 à 1955, l’OIT a adopté des normes sur les travailleurs “indigènes” dans les territoires coloniaux.

Le Panama a ratifié quatre des cinq conventions sur les travailleurs « indigènes » dans les territoires coloniaux qui ont été adoptés jusqu’en 1955 et elles sont toujours en vigueur pour ce pays. En outre, quand j’écris ce texte, la Convention no 107 relative aux populations aborigènes et tribales, adoptée en 1957, est toujours en vigueur pour ces deux pays. Si je voulais faire avancer la ratification de la Convention n° 169 au Panama, il m’a semblé important de rafraîchir mes idées en relisant le Traité de Versailles et de présenter ce contexte historique à mes interlocuteurs locaux.

Onze pays d’Amérique latine (Bolivie, Brésil, Cuba, Équateur, Guatemala, Haïti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Pérou et Uruguay) et très peu de délégués ont assisté à la Conférence de paix. Pour le Panama, il y avait le nom d’Antonio Burgos, ministre plénipotentiaire du Panama à Madrid, au sujet duquel je n’ai pu, lors de ma visite au Panama en 2016, recueillir aucune information particulière. Ce n’est que deux ans plus tard que j’ai consulté le bilan lucide de la Conférence de Paix et de la situation européenne publié par le délégué panaméen, en Italie, en 1925[1].

Alors que je préparais une visite au Panama, je me suis arrêté à nouveau au nom du délégué cubain qui avait signé l’Acte de la Conférence de Paix : Antonio Sánchez de Bustamante, qui a souligné ses titres les plus appréciés : Doyen de la Faculté de Droit et Président de la Société cubaine de Droit International, diplômes qui ont sans doute accru le respect pour sa personne et son pays.

Martinez Ortiz, le délégué cubain à la Commission de la législation internationale du travail, réapparaît sur la photo.

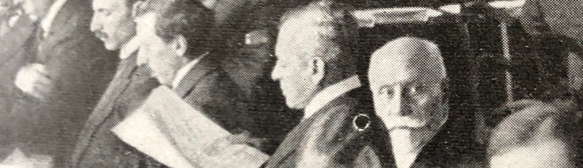

En ces jours de mai 2016, alors que je préparais encore la mission au Panama, Fiona Rolian – l’animatrice du groupe d’amis et de retraités de l’OIT sur Facebook – a eu l’idée de publier la photo que je reproduis ci-dessous, dans laquelle un personnage se distingue avec une belle moustache aux cheveux gris, que je ne pouvais qu’associer immédiatement au numéro 17 de l’image de la Commission de la législation internationale du travail.

Cependant, les moustaches blanches de la photo précédente ont été immédiatement attribuées à Ethelbert Stewart, directeur du U.S. Bureau of Statistics.

Pour dissiper tout doute sur le visage de Don Antonio, j’ai cherché et trouvé sa photo sur Internet. Don Antonio avait un visage très triangulaire, avec une petite pointe de barbe blanche, qui ne coïncidait pas du tout avec le visage rond de celui qui portait ses moustaches blanches à la Commission de la législation internationale du travail.

Samedi 25 janvier 1919 : Don Antonio appareille de La Havane et le Dr Martínez Ortiz participe à la première réunion de la Commission de la législation internationale du travail.

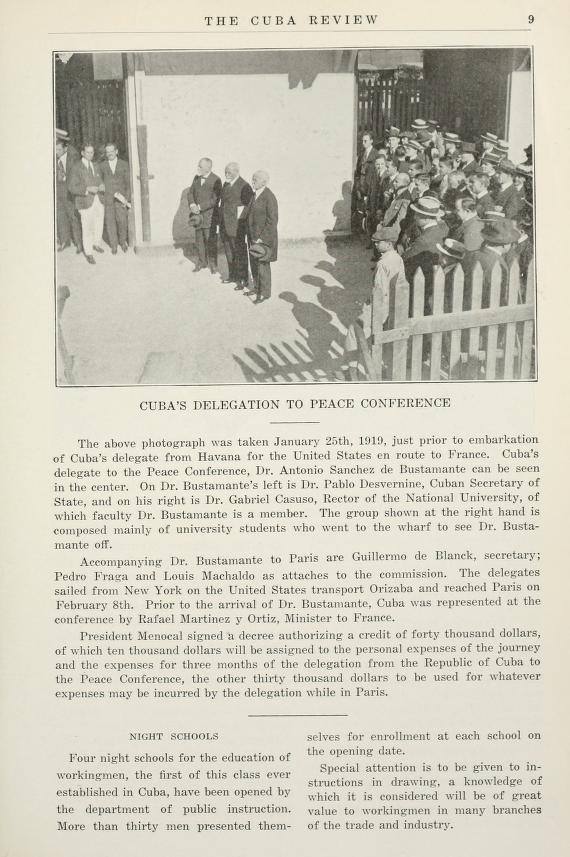

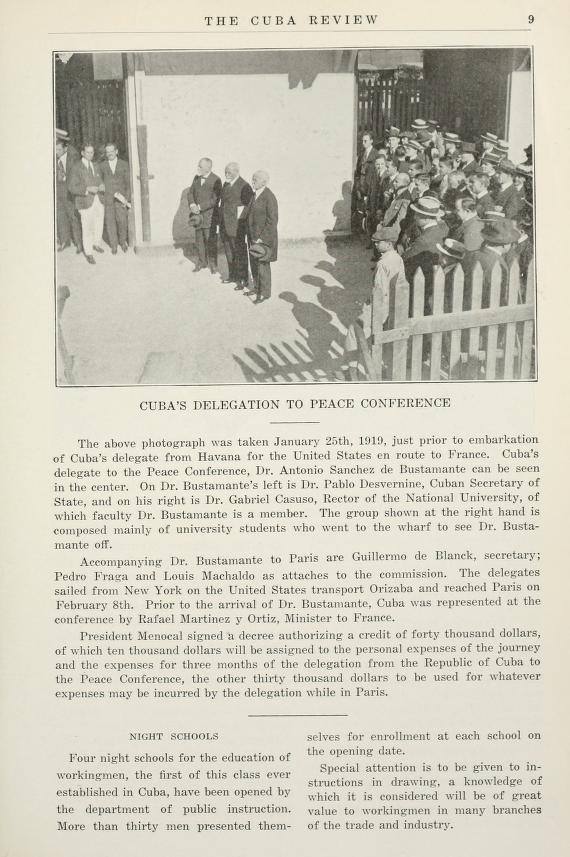

Sur le site Facebook susmentionné, où certains retraités de l’OIT passent une part importante de leur temps précieux, Fiona Rolian a également partagé une page de la publication illustrée The Cuba Review, qui offre un rapport sur le départ de Don Antonio à la Conférence de Paix.

D’après ce qui a été publié dans The Cuba Review, nous savons que Don Antonio a embarqué le 25 janvier 1919, en route pour la France. “Les délégués ont quitté New York par le navire américain Orizaba et sont arrivés à Paris le 8 février. Avant l’arrivée du Dr Bustamante, Cuba était représentée à la conférence par Rafael Martínez y Ortiz, ministre en France”.

En cherchant des informations sur Rafael Martínez Ortiz, j’ai trouvé dans un blog une photo du personnage qui correspondait le mieux au numéro 17 de la Commission de la législation internationale du travail. C’était le blog de Jorge Ferrer, un Cubain vivant à Barcelone, écrivain et traducteur du russe vers l’espagnol[2].

Jorge Ferrer a éveillé ma curiosité pour la vie et l’œuvre de Rafael Martínez Ortiz et m’a donné la première source de l’histoire d’amour que j’ai racontée à mes collègues en disant adieu à l’OIT. Je ne vais pas non plus anticiper une histoire d’amour réservée à ceux qui ont la patience de lire ce texte jusqu’à le fin.

En effet, il n’a pas été facile de vaincre la résistance des responsables des archives du BIT, mes chers Remo Becci et Jacques Rodriguez, et de les convaincre que le numéro 17 sur la photo n’était pas le prestigieux don Antonio, mais un médecin inconnu appelé Martinez Ortiz. Cependant, lorsque Remo Becci a révisé les versions précédentes des indications qui accompagnaient la photo de la Commission de la législation internationale du travail, le nom de Sánchez de Bustamente ne figurait pas dans une première version de la vignette, mais plutôt le nom de Martínez Ortiz.

Jacques a dû l’accepter sur Facebook : Après vérification, et grâce à la perspicacité de Natan, nous avons effectivement reconnu que la personne dont la silhouette correspondant à la vignette no.17 sur la photo de la Commission de la Législation internationale du Travail, n’était pas celle de Antonio Sánchez de Bustamante mais celle de Rafael Martínez Ortiz. Nous ferons la correction dans nos archives. Merci Natan Elkin d’avoir contribué à corriger cette erreur quelques 90 ans après.

Notons également qu’en 1926, lors de l’inauguration du premier siège du Bureau international du Travail, un document illustré reproduit la photo de la Commission de la législation internationale du travail, avec le nom (erroné) de Don Antonio. Je remercie Stanley Taylor, un autre membre éminent des Amis de l’OIT, qui a eu la gentillesse de partager, en juin 2018, le livret sur l’inauguration du bâtiment, publié en 1926.

Je répète que, très peu de jours après avoir quitté le Bureau, il me semblait avoir atteint le point culminant de ma carrière professionnelle : corriger une erreur qui durait depuis 90 ans et permettre aux nouvelles générations de connaître le nom et le visage du délégué cubain qui a souffert du froid de Paris, avec le sourire, entouré des très éminentes personnalités qui composaient la Commission de la législation internationale du travail.

La date et les personnalités de la photographie: 25 janvier / 1er février 1919

Les comptes rendus détaillés du Commission de la législation internationale du travail ont été publiés au Journal officiel du Bureau et sont disponibles sur Internet[3]. De cette façon, il est possible d’identifier, avec le numéro correspondant dans la vignette de la photo, les personnalités qui se sont rencontrées le 25 janvier 1919 pour entamer les discussions qui ont abouti à la création de l’OIT.

Le procès-verbal de la séance du samedi 25 janvier 1919, tenue au ministère du Travail, Hôtel du Ministre, Salle à manger, se lit comme suit :

La Conférence des Préliminaires de Paix, dans sa séance plénière du 25 janvier 1919, […] a décidé de nommer, pour l’étude de la législation internationale du travail, une Commission composée de quinze membres, à raison de deux membres pour chacune des Grandes Puissances (Etats-Unis d’Amérique, Empire britannique, France, Italie, Japon) et de cinq membres élus pour l’ensemble des Puissances à intérêts particuliers. Dans la Réunion tenue par ces Grandes Puissances, le 27 janvier 1919, la Belgique a été choisie pour désigner deux Représentants et Cuba, la Pologne et la République Tchéco-Slovaque chacun un Représentant. (…). La composition de la Commission, à la suite de la désignation de ses Représentants par chacun des Etats intéressés, se trouve ainsi être la suivante :

Etats-Unis d’Amérique : Hon. A. N. Hurley (18), Président de la Commission des transports maritimes ; M. Samuel Gompers (23), Président de l’American Federation of Labor.

Empire britannique : The Rt. Hon. G. N. Barnes (24), Ministre sans portefeuille ; Sir Malcolm Delevingne (25), K.C.B., Sous-Secrétaire d’Etat permanent à l’Intérieur.

France : M. Colliard (22), Ministre du Travail et de la Prévoyance sociale ; M. Loucheur (26), Ministre de la Reconstitution industrielle.

Italie : Le baron Mayor des Planches (4), Ambassadeur honoraire, Commissaire général de l’Emigration ; M. Cabrini, député.

Japon : M. Otchiai, Envoyé extraordinaire et Ministre plénipotentiaire de S. M. l’Empereur du Japon à La Haye ; M. Oka, ancien Directeur des Affaires commerciales et industrielles au Ministère de l’Agriculture et du Commerce.

Belgique : M. Vandervelde (21), Ministre de la Justice, Ministre d’Etat ; M. Mahaim (14), Professeur à l’Université de Liège, Secrétaire de la section belge de l’Association internationale pour la protection légale des travailleurs.

Cuba : M. de Bustamante, Président de la Société cubaine de droit international, Professeur à l’Université de la Havane. Remplacé provisoirement par : M. Rafael Martinez Ortiz (17), Envoyé extraordinaire et Ministre plénipotentiaire de Cuba à Paris.

Pologne : Le comte Jean Zoltowski (15), Membre du Comité national polonais (Délégué provisoire).

République Tchécoslovaque : M. Bénès (16), Ministre des Affaires Etrangères.

A la fin de la réunion, la commission disposait d’un bureau dans lequel chacune des cinq Grandes Puissances obtenait une place, bien que le ministre Loucheur (26) s’opposât cordialement à la nomination de deux secrétaires généraux et acceptait seulement que H. B. Butler (20) soit attaché à A. Fontaine (1). La composition du bureau était la suivante:

Président : Samuel Gompers (23) (Etats Unis).

Secrétaire général : M. Arthur Fontaine (1) (France).

Secrétaire général adjoint : M. H. B. Butler (20) (Empire Britannique)

Secrétaires :

Etats-Unis d’Amérique : M. Guy H. Oyster (11).

Italie : M. G. E. di Palma Castiglione (6).

Japon : M. Yoshisaka.

Belgique : Comte G. de Hemericourt de Grunne.

Liaison avec le Secrétariat général de la Conférence : M. J. Duboin.

Le procès-verbal nous permet également de déterminer que le Dr Martínez Ortíz était présent le 25 janvier et les 1er, 4 et 5 février. Après ces quatre réunions, le Dr Martinez Ortiz a été remplacé par Don Antonio. Parmi les quatre fois où le Dr Martínez Ortiz était présent, le ministre des Affaires étrangères de la République tchécoslovaque, Eduard Benes, n’était présent que les 25 janvier et 1er février. Il n’y avait pas d’autre jour où le Dr Martínez Ortiz et Benes auraient pu coïncider. Par conséquent, la photo a été prise le 25 janvier ou le 1er février 1919.

Visages souriants et tensions entre alliés

En souhaitant la bienvenue le 25 janvier 1919, le ministre Colliard propose que Sam Gompers soit élu président de la commission, ce qui donne lieu à des manifestations unanimes de soutien. Le comte Zoltowski a déclaré dans le procès-verbal qu’il était “heureux de voir M. Gompers élu Président” et a ajouté quelques mots que je suppose que Gompers a mieux compris que les autres membres de la commission: « Les ouvriers polonais ont trouvé aux Etats-Unis un excellent accueil ; ils sont répartis dans les usines d’un grand nombre de pays et ont grand intérêt à l’établissement d’une législation internationale ». Sam Gompers est né à Londres, en 1850, dans une famille juive d’Amsterdam et a suivi des cours dans une école juive laïque pendant son enfance. Quand Sam avait 13 ans, la famille Gompers s’est installée dans le Lower East Side de New York. Les ouvriers polonais que le comte Zolotowski avait à l’esprit étaient, dans une large mesure, des Juifs, victimes de meurtres collectifs, comme ce fut le cas à Lemberg, deux mois seulement avant la réunion de la commission, du 21 au 23 novembre 1918[4].

Si j’évoque les événements de Lemberg qui, à l’époque, se trouvait en territoire polonais et aujourd’hui en Ukraine (la ville s’appelle Lviv), c’est pour souligner que, malgré les sourires unanimes que l’on voit sur la photo, les affrontements entre les pays qui sont sur la photo se sont également multipliés à cette époque. Le 23 janvier 1919, l’armée tchécoslovaque s’était emparée de la ville de Tesen sur le territoire polonais[5], mais cela n’empêcha pas l’éminent Eduard Benes (16) d’être photographié juste à côté du comte Zolotowski (15).

Le samedi 24 janvier 1919, le Président Woodrow Wilson, présent à la Conférence, tenta d’imposer l’ordre entre les délégations : les actes de force porteront gravement préjudice aux revendications de ceux qui utilisent de tels moyens sous-entendant que ceux qui emploient la force mettent en doute la justice et la validité de leurs revendications et impliquent que leur but est d’établir leur souveraineté par la contrainte plutôt que par préférence raciale ou nationale et l’association historique naturelle… S’ils attendent justice, ils doivent renoncer à la force et remettre leurs revendications de bonne foi aux mains de la Conférence de paix. [Texte en anglais repris de l’ouvrage de Carole Fink mentionnée à la note 5: “the presumption that those who employ force doubt the justice and validity of their claim” and imply that their purpose was to “set up sovereignty by coercion rather than by racial or national preference and natural historical association… if they expect justice, they must refrain from force and place their claims in unclouded good faith in the hands of the Conference of Peace”].

Voyant qu’un délégué cubain était membre de la commission, je suppose aussi que Gompers, a ressenti une émotion personnelle. Comme son père, Samuel avait travaillé dans la fabrication de cigares. En 1875, il est élu président de la section locale 144 de l’Union internationale des fabricants de cigares et, jusqu’à sa mort en décembre 1924, il a occupé la première vice-présidence du Syndicat des fabricants de cigares. Les biographies de Gompers soulignent ses relations avec Cuba : “Gompers, qui avait des liens avec les travailleurs cubains du cigare aux États-Unis, a appelé les Américains à intervenir à Cuba ; il a soutenu la guerre avec l’Espagne en 1898. Il a cependant rejoint la Ligue anti-impérialiste, après la guerre, pour s’opposer au projet du président William McKinley d’annexer les Philippines[6]“.

Le code génétique de l’OIT se trouve sur la photo

L’OIT est définie comme une institution “tripartite” au sein de laquelle un consensus est recherché entre les représentants des gouvernements, des employeurs et des syndicats pour atteindre les objectifs de l’Organisation. L’origine du tripartisme se trouve dans cette commission de la conférence de paix qui, en plus d’avoir des délégués gouvernementaux, avait associé des personnalités représentant les syndicats (Sam Gompers (23), Leon Jouhaux (2)), les employeurs, A. N. Hurley (18) et la société civile, comme E. Mahaim (14), professeur à l’Université de Liège et secrétaire du comité belge de l’Association internationale de législation du travail.

L’Association internationale de législation du travail, association privée créé à Bâle en 1901, avait des correspondants dans différents pays et cherchait à diffuser et à analyser les législations novatrices adoptées au niveau national pour réglementer les conditions de travail. Sir Malcolm Delevingne (25), sous-secrétaire anglais à l’Intérieur, était également un membre actif de cette association, tout comme Arthur Fontaine (1), directeur de l’Office du Travail.

Les personnalités les plus en vue sont en première ligne de la photo : Sam Gompers (23), président de la principale confédération syndicale nord-américaine, avec les quatre ministres des grandes puissances : Pierre Colliard (22), ministre français du Travail, à sa gauche ; et G. N. Barnes (24), ministre britannique sans portefeuille, et Louis Loucheur (26), ministre français de la Reconstruction industrielle, à sa droite. Ainsi que E. Vandervelde (21), ministre belge de la Justice, avec son acolyte E. Mahaim (14), un représentant de l’Association internationale de législation du travail, ont réussi à se glisser dans la première rangée.

Albert Thomas, qui avait précédé Louis Loucheur (26) comme ministre français de l’Armement, sera élu premier directeur du Bureau grâce à l’action conjointe d’Arthur Fontaine (1) et de Léon Jouhaux (2) qui parviennent à battre le candidat britannique Butler (20). Quand A. Thomas meurt (mai 1932), Butler (20) occupera la direction du Bureau jusqu’en décembre 1938. L’Américain John Winant, qui était déjà directeur général adjoint, a servi pendant une courte période (1939-1941) comme directeur. Une autre personnalité déjà présente sur la photo, E. Phelan (5), dirigera le Bureau jusqu’en 1948 (reconverti de britannique en irlandais).

Le prix Nobel de la paix de 1951, décerné à Léon Jouhaux (2), personnalité marquante du syndicalisme français, se distinguera comme représentant syndical au Conseil d’administration de l’OIT. De même pour A. Fontaine (1), qui avait été élu premier président du Conseil d’administration du BIT, occupera ce poste jusqu’à sa mort (septembre 1931). Gabriel Ventejol (1919-1987) appartenait au même mouvement syndical français que Jouhaux, CGT Force Ouvrière, qui l’a accompagné et l’a finalement remplacé comme représentant syndical au conseil d’administration. En 1977 et 1984, Gabriel Ventejol a présidé deux séries de discussions sur les normes internationales du travail qui demeurent le substrat de la politique normative de l’OIT et certaines des questions en suspens sont toujours d’actualité pour l’Organisation.

Ma conclusion est que le profil des personnalités qui se sont réunies en 1919 pour créer l’OIT continue à conditionner la vie de l’Organisation à ce jour. L’actuel directeur général, Guy Ryder, est un syndicaliste britannique profondément enraciné à Bruxelles, siège des principales organisations syndicales social-démocrates et chrétiennes. A l’exception d’une décennie chilienne de Juan Somavía (1999-2008), les directeurs généraux britanniques (Butler, Jenks et Ryder) / irlandais (Phelan) ; français (Thomas, Blanchard) ; nord-américains (Winant, Morse) et, évidemment, un belge (Hansenne) ont alterné au Bureau.

Quatre aristocrates sur la photo

Le Baron Edmond Mayor des Planches (4) a eu une carrière diplomatique fructueuse en Italie, bien qu’il soit né à Lyon (France) dans une famille juive du canton de Vaud (Suisse), selon l’encyclopédie Treccani.

A gauche du Baron Edmond (4) et à droite de Léon Jouhaux (2), il y a un chapeau et une moustache chaplinesque correspondant au jeune Baron Robert Capelle (3). Le Baron R. Capelle a poursuivi une carrière diplomatique jusqu’à ce qu’il devienne chef de cabinet du ministre E. Vandervelde (21) (en 1926). Par la suite le Baron R. Capelle a été nommé secrétaire du roi Léopold III, qui lui donnera la dignité de comte. Le Comte Robert devra répondre aux accusations de collaboration avec l’occupant nazi qui ont conduit à l’abdication du roi Léopold III. Je suis intrigué qu’ils soient côte à côte sur la photo, L. Jouhaux (2), qui a résisté et combattu le nazisme, et le comte Robert (3), qui a collaboré à l’occupation nazie de son pays.

On trouve également le Comte Zoltowski (15), qui figure en tant que membre du Comité national polonais. En effet, la République de Pologne n’a été créée qu’à la fin de la Conférence de Paix. Et la famille Zolotowski a été enterrée à Buenos Aires par Lázaro Costa, la plus réputée compagnie de pompes funèbres, au seul cimetière digne de son rang, La Recoleta.

Le dottore Guglielmo Emanuele di Palma Castiglione (6), né à Turin en 1879, appartenait également à une famille noble. Après s’être occupé des migrations[7] au ministère des Affaires étrangères, il entre au Bureau le 1er février 1920 et prend sa retraite en décembre 1937. G. E. Di Palma Castiglione a publié, dans une prestigieuse revue florentine, une analyse de la XIe session de la Conférence internationale du travail[8] qui a retenu l’attention de Antonio Gramsci dans la prison fasciste[9].

Cuba à la Conférence de Paix

Cuba a été le dernier territoire américain à obtenir son indépendance de l’Espagne lorsque le traité entre les États-Unis et l’Espagne a été signé à Paris en décembre 1898. Ce n’est qu’en 1902 que Cuba a élu un président né sur l’île, Mario García Menocal. Le général Menocal a occupé la présidence pendant deux mandats consécutifs (1913-1917 et 1917-1921). Toujours alignée sur la politique étrangère américaine, la décision de Menocal de déclarer la guerre à l’Empire allemand et de participer à la Première Guerre mondiale a été le premier acte international du pays.

La déclaration de guerre a été accompagnée de quelques aspects curieux et propres qui montrent leur volonté d’être visible sur la scène internationale. Cuba adopte une “loi sur l’aide financière aux alliés’’ qui autorise des crédits pour le soutien à des hôpitaux, des ambulances des hospices que pourra établir la Croix-Rouge cubaine en Europe et pour le soutien des soldats et des membres de leurs familles qui ont été victimes de la guerre. Cette loi a créé la “Commission cubaine pour la propagande de la guerre et l’assistance aux victimes”. La population cubaine a également été encouragée à contribuer à l’effort de guerre des Alliés en faisant des dons d’espèces et de produits, principalement aux victimes de la guerre en France.

Il est important de rappeler une autre information, parue dans The Cuba Review, concernant les efforts déployés par le Gouvernement cubain pour appuyer sa délégation à la Conférence de paix: le Président Menocal a signé un décret autorisant un crédit de 40.000 dollars, dont 10.000 dollars seront affectés aux dépenses personnelles du voyage et aux dépenses pour trois mois de la délégation de la République de Cuba à la Conférence de Paix, les 30.000 autres dollars devant être utilisés pour toutes dépenses que la délégation pourra engager pendant son séjour à Paris.

L’Orphelinat de guerre cubain à Paris

La Esfera, le plus prestigieux journal illustré espagnol de l’époque, dans son édition du 3 mai 1919, a fait écho de la volonté de Cuba d’exprimer sa solidarité avec les victimes de la guerre en Europe. Dans l’édition du 3 mai 1919, une page entière signée Eduardo Zamacois[10] loue la performance de Cuba en Europe. La photo de la Première Dame, Doña Mariana Seva de Menocal, en sa qualité de Présidente du Comité des Dames de la Croix-Rouge, illustre la partie supérieure de la page du journal, tandis que dans la marge inférieure gauche figure la photo du Dr Martínez Ortiz, Ministre de Cuba à Paris.

Eduardo Zamacois ne peut s’empêcher de consacrer un compliment au Président Menocal et mentionne le diplôme de génie civil qu’il a obtenu à l’Université Cornell et son activité professionnelle. Le président Menocal, également connu sous le nom de “el mayoral de Chaparra[11]” était “le directeur de la société sucrière la plus riche du monde”. En effet, c’était une activité rémunératrice pour les sucreries de placer du sucre cubain aux Etats-Unis, à un prix préférentiel, pour soutenir l’effort de guerre des alliés[12].

L’article de Zamacois souligne que le Dr Martinez Ortiz, ministre cubain à Paris, a proposé la création immédiate d’un “orphelinat de guerre” dans lequel cent enfants appartenant aux deux nations qui ont le plus souffert – la Belgique et la France – pourraient recevoir une éducation et un abri décents. L’initiative cubaine de protection des enfants européens est due, selon l’article, “au sénateur Cosme de la Torriente, et sa réalisation est due à la décision rapide du général Menocal et de son épouse, une femme toute tendre, douce comme une page de l’Évangile, en qui rivalisent la noble beauté du cœur et la chaude beauté créole du visage’’.

Si les lignes du journaliste pouvaient être mises à jour dans la langue officielle de l’OIT, on pourrait dire que les enfants européens recevront une éducation et un abri “décent” dans un orphelinat cubain à Paris. Toute mention de “la beauté créole chaleureuse du visage” de la Première Dame serait également supprimée des textes officiels. Il conviendrait d’examiner la relation entre Ana Torriente, la collègue qui a pris ma relève au Département des normes internationales du travail, et les initiatives de certains de ses nombreux illustres ancêtres, y compris certainement le sénateur Cosme de la Torriente, qui, selon Zamacois, a eu l’initiative de créer un orphelinat de guerre cubain à Paris.

Selon Zamacois, le gouvernement cubain couvrait tous les frais d’entretien des enfants belges et français qui seront installés dans l’”orphelinat de guerre cubain”. Dans le règlement de l’orphelinat, il avait été prévu que “l’étude de la langue espagnole est obligatoire”, avec l’intention d’attirer de nouveaux immigrants belges et français à Cuba.

Le délégué du Panama assure la coordination avec Cuba

Avant d’aller plus loin, il serait utile de savoir que la délégation cubaine jouit de la confiance des autres délégations latino-américaines présentes à la Conférence de paix. Selon Antonio Burgos, le délégué du Panama, “les forts – le Conseil suprême des Alliés – tenaient constamment des sessions secrètes, discutaient, résolvaient, exécutaient et ne faisaient connaître aux petites puissances que certaines de leurs décisions en session plénière. Dans ces délibérations, on nous a permis, pour les apparences, de faire valoir notre point de vue, mais sans que notre opinion soit prise en compte et moins que n’importe quelle de nos attitudes, contraires ou favorables, pourrait nuire les questions résolues au préalable par les seigneurs du Conseil suprême”[13].

Les délégués latino-américains, qui se réunissaient chaque semaine à l’hôtel Meurice, ont suivi les judicieux conseils de Don Antonio et accepté que seules les initiatives présentées par les grandes puissances alliées et associées (Etats-Unis, Empire britannique, France, Italie et Japon) puissent se développer à la Conférence de Paix[14].

La Paix de Versailles à la Chambre des représentants : le “triomphe cubain à Paris”.

En octobre 2009, mon cher ami et collègue Germán López Morales, en sa qualité de directeur du Bureau de l’OIT pour le Mexique et Cuba, a pris l’excellente initiative d’organiser une manifestation à La Havane au cours de laquelle, entre autres choses, nous avons promu la convention (no 144) sur la consultation tripartite (normes internationales du travail), 1976. La convention n° 144 vise à renforcer le tripartisme et les mécanismes de consultation entre les autorités gouvernementales et les représentants des organisations d’employeurs et de travailleurs.

Pendant l’année 2009, le Bureau n’a pas échappé à la frénésie qui entoure l’Organisation chaque fois que l’année grégorien termine en 9. Le document que j’ai élaboré pour présenter la convention no 144 à Cuba devait contribuer également à commémorer l’anniversaire de l’Organisation et, en liaison avec les autorités locales, j’ai souligné ce qui était possible de voir que Cuba avait fait pour adhérer à la convention sur les consultations tripartites concernant les normes internationales du travail.

Avec assez d’innocence, il m’a semblé évident qu’il serait bon de féliciter nos interlocuteurs cubains du travail de Don Antonio à la Conférence de Paix. De plus, nous avions la photo qui montrait que Cuba avait été présent au moment magique et exclusif de la création de l’Organisation internationale du travail.

Avec la collaboration d’une stagiaire mexicaine excellente et inoubliable, le Dr Montserrat González Garibay, j’ai eu la chance de trouver un document inattendu : le discours prononcé par Fernando Ortiz[15], en sa qualité de vice-président de la Chambre des représentants, à la séance du 4 février 1920, séance consacrée à l’examen de l’adhésion de Cuba à la Société des Nations.

Selon Don Antonio, la prestation de la délégation cubaine méritait d’être considérée comme un “triomphe cubain à Paris”. Malheureusement, je n’ai pas accès à la documentation gouvernementale soumise à la Chambre des représentants ni au discours prononcé par Don Antonio.

La lecture du pamphlet publié par F. Ortiz[16] laisse planer des doutes sur le triomphe de Cuba à Paris. F. Ortiz critique en termes généraux le gouvernement Menocal pour avoir retardé la présence de Don Antonio à Paris et souligne les actions de “notre adroit ministre plénipotentiaire à Paris, le Dr Rafael Martínez Ortiz “. Par la suite, F. Ortiz se félicite de l’intervention du Dr Martinez Ortiz devant les autorités françaises pour empêcher une augmentation des droits de douane français sur les importations de tabac cubain – “un simple problème d’ajustement du tarif douanier qui a été résolu avec l’habilité et l’expertise que chacun reconnaît au Dr Martinez Ortiz ” (page 7).

F. Ortiz indique que “[…] notre premier Délégué a dû représenter Cuba aux premières sessions des Conférences et obtenir un succès, après avoir obtenu de ce congrès des nations que la République de Cuba puisse être représentée… précisément dans une des sections les plus importantes, dans laquelle va se développer la législation mondiale du travail ” (page 8).

Selon F. Ortiz, “l’un des délégués belges” (Emile Vandervelde ou Ernest Mahaim) a proposé au Dr Martinez Ortiz de participer à la Commission de la législation internationale du travail “représentant toute l’Amérique du Sud, avec l’accord de nos sœurs d’indépendance, de lignage et de culture”… “Cuba fut admis comme le porte-drapeau de toute une civilisation” (pages 8-9).

Don Antonio aurait affirmé devant la Chambre des représentants que, grâce à la création de l’Organisation du travail, la Conférence de paix avait aboli “l’esclavage économique du travailleur”. Bien que F. Ortiz reconnaisse que “la charte fondamentale du prolétariat” a été rédigée à Paris, il tempère l’ardeur de Don Antonio et s’arrête à l’article 427 du Traité de paix qui énumère les neuf principes et méthodes auxquels une importance particulière et urgente est accordée afin d’atteindre les objectifs de l’Organisation du travail.

F. Ortiz développe un argument en opposant la lettre de l’article 427 du Traité de paix à la réalité des travailleurs cubains (pp. 27-28) qui mérite d’être rappelé :

(…) « Le traité stipule que le travailleur ne peut plus être considéré comme une marchandise[17], tandis que le délégué de Cuba, comme celui d’autres gouvernements, penserait peut-être que dans sa patrie, le travailleur continue d’être une marchandise, librement échangée, impuissant face à l’assaut de l’offre et de la demande, comme le sucre ou le tabac, sans que l’embauche mérite une protection spéciale dans notre législation.

Ce traité établit que le travailleur doit gagner un salaire minimum suffisant pour satisfaire ses besoins selon la nature et la culture ; alors que, là aussi, le travailleur n’a que son propre syndicat comme défense et l’État a des employés qui ne reçoivent que 40 ou 50 pesos par mois, insuffisants pour une vie saine et décente.

Il est inscrit dans la charte fondamentale du travailleur que la libre syndicalisation des employeurs et des travailleurs est libre, alors qu’ici… ni l’exercice le plus inoffensif du droit de réunion n’est permis, ni le syndicalisme généralement garanti quand il n’est pas pratiqué pour accumuler des biens. Le temps de travail quotidien n’a pas encore été légiféré dans nos régions, alors qu’il est déjà devenu un précepte du traité de paix, (…).

La réparation des dommages subis par les accidents du travail, qui apparait dans le texte du Traité, dispose à Cuba d’une consécration légale pompeuse mais pas appliquée et falsifiée par les règlements gouvernementaux.

Les femmes qui, dans le Traité de paix, conquièrent le droit international à la protection publique en tant que travailleuse et en tant que mère, ne méritent pas d’être protégées par la loi à Cuba.

Les signataires du traité de Versailles veulent que chaque État dispose d’un corps d’inspecteurs du travail, composé d’hommes et de femmes, peut-être pour encourager les gouvernements qui, comme celui de Cuba, n’ont pas encore réussi à organiser un centre gouvernemental et officiel capable d’affronter et de diriger tous ces conflits sociaux avec la compétence et l’énergie requises. »

Cette relecture d’une disposition conventionnelle à la lumière des réalités nationales sera une ressource oratoire fréquemment utilisée par les délégations à la Conférence internationale du Travail. Cette méthode permet d’exagérer à quel point on se rapprochait ou s’éloignait au niveau local des objectifs d’une disposition des normes internationales du travail.

En tout état de cause, F. Ortiz était conscient de la portée universelle des idéaux de l’OIT et, en concluant son discours, il a dit avec insistance :

“Aux membres de cette assemblée d’une jeune nation : les libertés que nous consacrons ici n’empêchent pas que d’autres libertés issues de la réforme républicaine du gouvernement et la liberté individuelle doivent être respectées par les pouvoirs publics ! Que l’ingéniosité diplomatique de Versailles soit mieux respectée que l’ingéniosité traditionnelle de Cuba ! (…)

“Si nous continuons à nous abandonner aux ambitions incultes et aux impulsions réactionnaires de l’injustice, notre situation dans le monde sera plus que modeste : nous continuerons comme avant, à la lisière du chemin de la vie : paresseux, endormis, sans entendre les cris des nations qui marchent et demandent, en haillons, l’aumône de la justice et du respect de notre souveraineté, aux grandes nations qui, au galop de leur civilisation, nous laissent sur le chemin de l’avenir, haletant et mordant la poussière du progrès qui s’éloigne.”

Imaginant que mes interlocuteurs cubains d’octobre 2009, connaissaient les paroles que F. Ortiz avait prononcé en 1920, et qu’ils pourraient objecter que l’OIT n’avait pas non toujours épuisé le mandat de 1919, je me suis permis d’ajouter un commentaire personnel qui disait : Dans le contexte actuel, certaines des affirmations précédentes sont toujours valables : le fossé entre le droit international du travail et son application dans un grand nombre de pays est encore considérable. Le principe de la consultation tripartite contenu dans la convention no 144 prend de l’importance dans ce contexte en tant que pont entre la réalité nationale et les principes internationaux.

Un peu plus d’un an après le débat au Parlement, la délégation cubaine a obtenu une véritable victoire à la Société des Nations. Le triomphe cubain s’est produit à Genève dans la belle matinée du 14 septembre 1921, lorsque la délégation cubaine, dirigée par l’illustre Cosme de la Torriente, a obtenu l’élection de Don Antonio comme juge à la Cour permanente de justice internationale[18]. Quelques années plus tard, cependant, la réélection de Don Antonio rendra furieux C. Wilfred Jenks alors qu’il était encore étudiant à l’Université de Cambridge, avant de commencer une brillante carrière au Bureau.

Jenks : Don Antonio et ses amis, une nuisance pour la Société des Nations

Malgré toutes les bonnes choses à penser de Don Antonio, peu de temps avant d’être recruté au service juridique du Bureau et d’entamer une brillante carrière qui aboutira au poste de Directeur général, Jenks[19] affirme qu’il existe un ‘Latin-American problem in the League of Nations’.[20]

Selon Jenks, les problèmes de la Société des Nations sont dus au fait que Cuba a réussi à bloquer le consensus requis pour l’entrée en vigueur de la réforme du Statut de la Cour permanente. Avant de participer au consensus, la délégation cubaine a voulu s’assurer que Don Antonio renouvelle son mandat de juge à la Cour permanente :

[…] it was loudly whispered in the Assembly couloirs that the only motive of the Cuban Government was a desire to protect the vested interest of a particular member of the Court. Then came the Court elections and Judge Bustamante, the individual in question, was triumphantly re-elected to his position by the caucus and their allies[21].

En effet, selon Jenks, trois pays des “Caraïbes” (Colombie, Cuba et… El Salvador) ont eu l’audace de demander par écrit de leur réserver des postes de juges, ce qui a permis à Jenks d’exprimer son inquiétude quant à l’absence du Brésil et du Chili à la Cour permanente :

[…] Chilean[22] and Brazilian[23] candidates of great personal distinction failed to secure election and three judges were chosen from the Caribbean States. For the Portuguese variant of Latin-American law no place has been found upon the new court and the three Latin-American judges who will take office on January 1st are therefore less representative of the principal legal systems of the world than were their two predecessors.

Jenks identifie les deux autres audacieux mousquetaires (les délégués de la Colombie et du Salvador à la Conférence de la Société des Nations) coupables d’avoir triomphé dans leur manœuvre et obtenu leur propre nomination à la Cour permanente :

But Judge Bustamente will doubtless revel in the company of Dr. Guerrero[24], of Salvador, and Señor Urrutia[25] of Colombia, both of whom signed the letter claiming three Latin American places on the Court, the Statue of which their governments had not then ratified although they had signed in 1920

Bien qu’il soit compréhensible que le jeune Jenks ait eu ses préférences parmi les pays d’Amérique latine, rien ne permet de dire qu’El Salvador soit un pays des Caraïbes. En tout état de cause, les personnalités des juristes Urrutia et Guerrero, ainsi que celle de Don Antonio, étaient parfaitement adaptées en tant que représentants de la culture du continent. L’attitude militante du jeune Guerrero anticipe son comportement exemplaire en tant que président lorsqu’il parvient à soustraire les archives de la Cour permanente à l’armée allemande qui occupe La Haye pendant la seconde guerre mondiale.

Sans entrer dans une analyse du travail accompli par les juges latino-américains de la Cour permanente, tout indique que Don Antonio était un bon juge. Le juge Sánchez de Bustamante a émis deux opinions dissidentes : en ce qui concerne la compétence de la Cour permanente, dans l’affaire des concessions Mavrommatis en Palestine, août 1924, et dans le jugement sur les emprunts serbes, juillet 1929. Don Antonio s’opposa également à la majorité de la Cour permanente dans l’arrêt rendu en juillet 1923 sur la Carélie orientale.

Stanley Taylor a publié sur Facebook une photo des délégués latino-américains qui ont participé à la VIIIème réunion de l’Assemblée de la Société des Nations (septembre 1927), honorée par Motta, président de la Confédération suisse, et Thomas, directeur du Bureau, prise le lundi 26 septembre 1927, publiée par La Patrie Suisse, le 5 octobre 1927, où apparaissent Guerrero et Urrutia.

A la page 171 de la brochure publiée par le Secrétariat de la Cour internationale de Justice, La Cour permanente de Justice internationale, 1922-2002, il y a une belle image, prise en mai 1937, du Dr Guerrero marchant sur les rives de la Meuse près de la ville hollandaise de Limmel, en conversation avec Don Antonio, et à ses côtés, sa jambe droite bien avancée et la main gauche dans la poche, le greffier de la Cour permanente, Julio López Oliván[26].

Cuba, 1928 : 16 conventions internationales du travail ratifiées

Jenks reconnaît dans son article qu’en 1931, Cuba était le Membre latino-américain ayant ratifié le plus grand nombre de conventions internationales du travail (16 ratifications), un nombre si élevé que les États-Unis d’Amérique n’ont pu atteindre ce chiffre un siècle après la création de l’OIT. Ceci dit, sauf pour des périodes exceptionnelles, les États-Unis ont un dialogue social fluide et des consultations tripartites efficaces, alors qu’à Cuba, malgré mes efforts, il n’y en a toujours pas.

On ne peut éviter une autre parenthèse et revenir aux aventures de Rafael : le Dr Martínez Ortiz étant Secrétaire d’Etat de la République, le Bureau enregistre – les 7 juillet[27] et 6 août 1928[28] – la ratification par Cuba de 16 conventions internationales du travail. Jacques Rodriguez m’a permis de consulter les 16 instruments de ratification : tous les documents portent la signature du Président Machado et le sceau du Secrétariat d’Etat… mais les instruments de ratification ont été signés par J. M. Fernández, en sa qualité de “Secrétaire de la Santé et des Affaires sociales et d’Etat intérimaire”.

Malgré la crise économique internationale, le Dr Martinez Ortiz avait d’autres activités importantes à mener qui l’ont forcé à quitter son bureau….

La vie et la carrière du Dr Martínez Ortiz

Rafael est né à Santa Clara le 20 décembre 1857. Rafael était le fils de José Martínez Ortiz, originaire de Santander en Espagne, et de la Cubaine Cristina López-Silvero Ledón. Son nom et prénom d’origine étaient Rafael Martínez López.

Les grands-parents paternels de Rafael étaient Joaquín López-Silvero et Rudesinda Ledón. Le chirurgien Francisco Javier López(-Silvero) Ledón, son oncle, le frère de sa mère, était bien établi à Arenys de Mar, comme me l’a communiqué Hug Palou i Miquel, le directeur des Archives historiques Fidel Fita de la Mairie d’Arenys de Mar, près de Barcelone.

Après des études de médecine à Barcelone, Rafael retourne à Cuba et entame une carrière politique qui le mènera à la Chambre des représentants et au poste de secrétaire des Finances et de l’Agriculture pendant quelques mois en 1910.

En janvier 1912, le Dr Martinez Ortiz publie “Cuba. Les premières années de l’indépendance”, un livre dans lequel il se présente comme “témoin des événements qui ont eu lieu pendant la période constitutive de notre nation”. La première édition est dédicacée “À la ville de Santa Clara consacre cette œuvre. L’auteur”.

La deuxième partie du travail est consacrée à l’intervention américaine et à la mise en place du gouvernement de Tomás Estrada Palma, aux élections présidentielles de 1905, à la guerre civile, à la deuxième intervention américaine et au rétablissement de la République. Ce volume est publié à Paris en septembre 1920, alors que le Dr Martínez Ortiz représente son pays auprès du gouvernement français et participe à la Conférence de Paix. En 1926, Martínez Ortiz sera membre correspondant de l’Académie d’Histoire, par Santa Clara.

La troisième édition de l’ouvrage est également publiée à Paris, en 1929[29]. Dans cette édition, le Dr Martínez Ortiz ajoute une nouvelle dédicace :

HONORABLE PRÉSIDENT DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE, LE GÉNÉRAL GERARDO MACHADO ET MORALES. Monsieur le Président : Ce livre est dédié, dès sa première édition, à notre bien-aimée Villaclara ; mais je veux vous offrir, Honorable Président, fils le plus éclairé de notre ville natale, la troisième édition qui paraît aujourd’hui de mon œuvre, formée avec les souvenirs patriotiques des premières années de la vie nationale. Par conséquent, Monsieur le Président, je vous prie d’accepter l’offre simple et cordiale de votre ami et «coterráneo », Rafael Martínez Ortiz.

Jorge Ferrer assure que le travail du Dr. Martínez Ortiz mériterait toujours d’être lu et raconte dans sa note une scène que le Dr. Martínez Ortiz relate de la première rencontre entre Rafael Montoro[30] et Tomás Estrada Palma[31], où le président nouvellement élu assure à l’ancien dirigeant autonomiste : “Cuba sera la Suisse des Amériques ! Montoro montre la rue et demande : “Et où sont les Suisses ?”.

A l’occasion de la publication de la troisième édition de sa chronique de l’indépendance, le Dr Martínez Ortiz est secrétaire d’Etat, poste qu’il a occupé de novembre 1926 à décembre 1930.

Il convient de noter que Martínez Ortiz a été distrait par deux tâches collatérales : publier, à Paris, la troisième édition de son histoire de Cuba et faire construire, également à Paris, un mausolée dédié à la mémoire d’Emilia Rovira y Presas, son premier amour, un mausolée installé au cimetière municipal d’Arenys de Mar, en périphérie de Barcelone, sur la rive de la Méditerranée.

Sur l’amour perdu du docteur Martínez Ortiz à Arenys de Mar

Jorge Ferrer, écrivain et traducteur cubain basé à Barcelone, m’a rappelé l’article de Montserrat Calas, intitulé Ronda de Amor en Sinera, publié dans El País, le 24 mars 2000. L’histoire semble être une histoire d’amour banale entre la belle jeune femme d’une famille puissante (Elivra Rovira y Presas) et le fils du facteur du village (Rafael Martínez Ortiz). Le jeune homme prospère lorsqu’il part pour les Amériques, mais son être le plus cher meurt de chagrin, ne sachant pas que sa famille a intrigué pour lui cacher la correspondance amoureuse qu’elle avait reçue de Cuba.

Selon El País, les événements se sont déroulés comme suit :

Emilia Rovira était une belle jeune fille d’Arenys de Mar, fille d’une famille aisée – son père était procureur – qui tomba amoureuse de Rafael Martínez, un humble garçon, fils du facteur de la ville. Sa famille a entravé l’amour des deux jeunes gens et Rafael a décidé d’aller en Amérique pour faire fortune et revenir plus tard pour épouser sa bien-aimée. Mais la famille Rovira a intercepté les nombreuses lettres d’amour que le jeune homme a écrites de l’autre côté de l’Atlantique. A La Havane, Rafael a fait une carrière politique, a été Secrétaire d’Etat et représentant de Cuba à Paris. Ne recevant pas de réponse à ses lettres, il a cru qu’Emilia l’avait oublié et il avait épousé une jeune Cubaine aux Antilles. Emilia attendait le retour de son bien-aimé, mais le manque de nouvelles a fini par la consumer, jusqu’à ce que le chagrin et la tristesse prennent fin d’elle. Elle est morte de chagrin à l’âge de 33 ans.

Quelques temps plus tard, Rafael, déjà propriétaire d’une fortune importante et ayant une position sociale reconnue en tant que politicien et médecin, retourne à Arenys pour des raisons de travail. Apprenant son histoire, il commanda la construction d’un panthéon de marbre surmonté du buste d’Emilia, sculpté à partir d’une photographie que la jeune femme lui avait donnée peu avant son départ en Amérique. Le tombeau, qui a coûté 1.877 pesetas, a une dédicace discrète : “Son ami d’enfance, le Dr Rafael Martínez Ortiz, consacre ce souvenir à sa mémoire”. Rafael avait l’intention d’enterrer les restes de sa bien-aimée et de les transporter au panthéon, mais la famille de la jeune fille s’interposa à nouveau entre les deux amants et ne le permit jamais. Avant de fermer la tombe, Rafael déposa à l’intérieur une rose qui, selon la légende populaire, resta intacte.

El Mundo, à la même date, publie un article signé Jordi Andreu, avec le titre : Epilogue pour une histoire d’amour. Selon El Mundo, Rafael est né à Cuba et étudiait la médecine à Barcelone. La famille Rovira Oliver y Presas Canut a refusé que leur fille Emilia Mercedes Esperanza de Rovira Presas s’installe à Cuba avec le jeune docteur Rafael.

Le texte publié par El Mundo se lit ainsi :

Rafael MARTÍNEZ-ORTÍZ et Emilia ROVIRA ont commencé leur histoire d’amour à Arenys de Mar, où il avait déménagé de Barcelone, où il avait vécu et étudié la médecine. Cubain de naissance, il a souvent visité la ville du Maresme parce qu’il y avait un parent. C’est ainsi qu’il rencontra celle qui sera l’amour de sa vie. Mais ils ne se sont jamais mariés. La famille d’Emilia, d’origine aristocratique, a refusé de donner son consentement. Apparemment, la cause qui aurait pu empêcher son mariage est le fait qu’elle aurait dû abandonner sa famille pour s’installer à Cuba, “ce qui ne correspondait pas aux idées de l’époque”, a déclaré hier Elvira Ortiz, une des descendantes.

Rafael se rendit à Cuba, d’où il écrivit régulièrement à Emilia. Mais la jeune femme est morte de chagrin et d’amour à l’âge de 32 ans parce qu’elle n’a jamais reçu les lettres que Rafael MARTÍNEZ ORTÍZ lui avait envoyées. Les astuces de la famille d’Emilia les ont empêchés de vivre leur histoire d’amour et ont intercepté le courrier pour qu’Emilia n’ait pas de nouvelles de son bien-aimé.

A Cuba, Rafael MARTÍNEZ-ORTÍZ est devenu une figure publique importante au lendemain de la guerre d’indépendance. Il a fait une importante carrière politique sur l’île des Caraïbes, d’où il a été envoyé à Paris en tant que représentant politique. Rafael, qui s’est marié à Cuba, a également fondé un journal sur son île natale. En 1926, il a été envoyé en Europe, ce qui lui a permis d’aller à Arenys de Mar afin de savoir où se trouvait feue Emilia ROVIRA. Après avoir appris la fin tragique de la jeune femme, MARTÍNEZ-ORTÍZ fit construire un panthéon de marbre noir où il voulait que les restes de son ancien amour soient placés. Rafael a commandé le panthéon à un sculpteur français, qui a sculpté un buste avec la belle image de l’Emilie à partir d’une photographie qu’elle avait donnée à Rafael avant son départ. Mais l’opposition des parents a persisté, et ils ont refusé ce transfert.

En effet, Rafael a étudié la médecine à l’Université de Barcelone. C’est encore Hug Palou i Miquel qui a mis de l’ordre dans mon histoire, en confirmant que Rafael Martínez Ortiz est né à Cuba et en identifiant le chirurgien Francisco Javier López(-Silvero) Ledón, oncle de Rafael, frère de sa mère, installé à Arenys de Mar.

Le mausolée d’Emilia

En mai 2018, avec mon fils Ariel, nous avons quitté Samois-sur-Seine, aux abords de la forêt de Fontainebleau[32] et sommes arrivés en voiture au cimetière municipal à Arenys de Mar. Le cimetière est situé sur la colline qui offre une vue panoramique sur la mer. Martinez Ortiz a choisi un emplacement particulièrement stratégique pour placer son mausolée au sommet de la colline. Lors de son inauguration, le mausolée dominait tout le cimetière de sa hauteur, ce qui était peut-être un message éternel laissé par le Dr Martinez Ortiz à ceux qui se sont opposés à ses amours de jeunesse.

Le regard sur le buste d’Emilie ne fait qu’augmenter la tristesse de l’endroit.

Selon Hug Palou i Miquel, la municipalité d’Arenys de Mar reçut le buste d’Emilie durant l’été 1929 et l’été suivant, les pièces du mausolée furent envoyées pour être assemblées dans le cimetière municipal. Palou i Miquel a bonifié ce récit en apportant les précisions suivantes: “En realité, le Dr. Martínez-Ortiz a été en contact permanent avec José Casdemont, le curé de la paroisse, son représentant dans tout cette affaire, et il a aussi échangé périodiquement avec le maitre de l’ouvrage du mausolée, Antonio Rossell. [Casdemont et Rosell] ont recu les pièces et le buste”.

Comme l’indique l’inscription à droite du mausolée, c’est un entrepreneur de pompes funèbres français, les établissments Thoin, à qui le Dr Martínez Ortíz a confié le mausolée et un sculpteur français qui a sculpté le buste d’Emilia.

Les établissements Thoin pousuivent leurs activités au 4 avenue du Cimetière, adjacent au cimetière parisien de Saint Ouen (à ne pas confondre avec le cimetière de la mairie de Saint Ouen, très proche de la sortie du métro Mairie de St Ouen, depuis la très populaire ligne 13). Pour se rendre aux établissements Thoin, longez les belles rues de Saint Ouen et vous trouverez la (petite) avenue du Cimetière.

En arrivant au salon funéraire, j’ai trouvé une très bonne équipe, surprise par les photos que je leur ai montrées du monument que l’entreprise avait construit en 1929 et transporté en 1930. Malheureusement, ils n’avaient pas conservé d’archives de l’époque permettant d’identifier le sculpteur du buste. Il n’y a pas non plus de restes de la correspondance que le Dr Martínez Ortiz a probablement échangée avec les établissments Thoin pour discuter de la construction du monument et de son transfert de Saint Ouen à Arenys de Mar.

Comme on me l’a dit au salon funéraire, le mausolée a été construit en marbre granitique provenant d’une carrière vosgienne dont l’exploitation a été interrompue il y a des années. L’assemblage des différents blocs de marbre dans le mausolée a été réalisé à l’aide d’agrafes de ferraille, une technique traditionnelle d’ajustement des pierres.

Notes pour conclure et encore parler du centenaire de l’OIT

Quand j’ai commencé ce document, en relatant l’histoire de la naissance de Rafael Martínez Ortiz à Arenys de Mar qui avait été publiée dans El País, j’ai supposé que l’amour de Rafael pour Emilia et aussi pour la Catalogne avait duré toute sa vie.

Rafael Martínez Ortiz, un jeune homme né à Arenys de Mar, malgré sa passion pour l’indépendance et la politique étrangère de Cuba, son pays d’adoption, avait secrètement maintenu son engagement envers Emilia et la Catalogne, son pays natal, et vécu une bonne partie de sa vie à Paris.

L’histoire de Rafael, un diplomate latino-américain bloqué à Paris, recoupe dans une certaine mesure des éléments de ma propre vie. Lorsque j’ai quitté l’Argentine en août 1976, sans être directement influencé par la situation politique de l’époque, j’ai obtenu une bourse pour étudier le droit européen à l’Université catholique de Louvain. Dès mon arrivée à Leuven, la ville flamande où la Faculté de droit fonctionnait encore, j’ai participé au voyage organisé par le service pour les étudiants étrangers de l’UCL qui proposait une visite à Paris durant le long week-end de la célébration de l’armistice de la Première Guerre mondiale, une fête très importante en Belgique et en France.

Cette visite commémorative de l’armistice de novembre 1918, moment historique directement lié à l’origine de l’OIT, m’a permis d’établir, en novembre 1976, une liaison avec une belle et jeune parisienne. Pour mémoire, j’ai réussi à me faire accepter de la belle et jeune parisienne en lui parlant du droit européen des transports, l’intégration européenne était le sujet qui, à l’époque, nous passionnait mutuellement. La romance a été interrompue quand j’ai choisi d’épouser à Rome, à ma fiancée argentine, la mère de mes enfants Ariel et Javier.

Contrairement à Rafael et Emilia, la jeune parisienne et moi avons gardé secrètement les lettres que nous avons échangé entre Louvain et Paris. Vingt ans plus tard, séparé de la mère de mes enfants, je suis retourné à Paris et j’ai réussi à regagner l’attention de la belle parisienne, sans trop insister sur le droit communautaire ou les normes internationales du travail. Mon retour ne semble pas avoir été si désagréable étant donné que même sa propre mère a accepté de m’offrir une copie originale du Traité de Versailles de 1919, une source primordiale pour la rédaction de ce document.

Plus prosaïquement, la même semaine où j’ai pris ma retraite, j’ai obtenu la nationalité suisse, mettant fin à un de mes rêves du début de ma carrière de fonctionnaire international. Lorsque j’ai rejoint l’OIT, je ne pensais pas à mon pays d’origine et je croyais naïvement que travailler dans une agence des Nations Unies ferait de moi un “citoyen du monde”. Le Laissez-passer des Nations Unies a été le sésame qui m’a ouvert les portes de tous les pays et les couloirs privilégiés dans les aéroports pour le personnel des compagnies aériennes et les diplomates.

En rédigeant ce document, j’ai pu mieux connaître les circonstances vécues lors de la Conférence de Paix et le rôle joué par les seuls Latino-Américains présents à la Commission de la législation internationale du travail où l’acte fondateur de l’OIT a été élaboré. Le fait que le seul personnage latino-américain sur la photo prise le 25 janvier ou le 1er février 1919 soit finalement de Santa Clara ne cesse d’exciter mon imagination argentine.

Cependant, il m’a toujours semblé que la connaissance du contexte historique (géographique et économique) et la discussion des arguments de toutes les parties, fondés sur le droit, devrait persuader les secteurs impliqués dans un conflit social de renoncer à la violence. Mettre la violence de côté et accepter des procédures qui permettent de parvenir à des accords et à un consensus est au cœur des discussions en cours sur la consultation des peuples autochtones établi par la convention no 169.

Nous avons quitté Genève pour prendre notre retraite en Espagne et j’ai été très surpris de me retrouver en plein « procès » catalan. Le point de contact précis entre le « procès » catalan et les questions que j’ai abordées dans ce document se trouve dans le livre de Ph. Sands[33], qui prend comme point de départ le massacre des Juifs à Lemberg en novembre 1918 pour discuter les concepts de crime contre l’humanité et de génocide élaborés par deux juristes “lemberiks”, Hersch Lauterpacht et Rafael Lemkin.

La situation de la Catalogne était présente à la Conférence de Paix lorsque certaines délégations se sont opposées à la possibilité pour toute minorité de présenter ses revendications à la Société des Nations, sans aucun filtre du secrétariat et sans le consentement des gouvernements concernés : “It would clearly be inadvisable to go even the smallest distance in the direction of admitting the claim of the American negroes or the southern Irish, or the Flemings or Catalans to appeal to an interstate conference over the head of their own government. Yet if the right of appeal is granted to the Macedonian or the German Bohemians it will be difficult to refuse it in the case of other nationalist movements[34]”.

Un autre responsable britannique, en mai 1919, Sir James Headlam-Moreley, a indiqué :

“… il serait très dangereux de permettre aux habitants ou aux citoyens de tout État de faire appel directement à la Société des Nations, et pas seulement par l’intermédiaire de leurs gouvernements. Si ce principe est violé, on pourrait arriver à une situation où, par exemple, les francophones du Canada, les juifs américains, les catholiques d’Angleterre, les Gallois, les Irlandais, les Écossais, les Basques, les Bretons ou les Catalans pourraient se tourner vers la Société des Nations et dénoncer les abus dont ils ont été victimes[35]“.

Les revendications catalanes n’ont pas pu être discutées devant la Société des Nations[36]. Outre les obstacles formels, les initiatives catalanes auraient dû surmonter les réticences de l’un des fonctionnaires les plus éminents de la section pour la protection des minorités, Pablo de Azcárate[37], qui, entre 1922 et juillet 1936, a travaillé dans cette section et en a également été le directeur[38].

Ce qui m’a surpris dans la performance de Pablo de Azcárate dans la section sur la protection des minorités est résumé dans cette phrase, écrite en juillet 1929 : « je ne crois pas possible d’affirmer que la Société des Nations soit appelée à prêter secours aux minorités, mais plutôt à garantir l’exécution des Traités sur les Minorités »[39].

À mon avis, cette pensée de Pablo de Azcárate reflète les difficultés que rencontre l’OIT lorsqu’elle laisse en suspens certaines questions particulièrement difficiles, notamment en ce qui concerne les minorités ethniques.

Les minorités ethniques se plaignent à l’OIT des persécutions dont elles sont victimes. Les mécanismes de contrôle de l’OIT ne semblent pas à la hauteur des attentes des groupes les plus vulnérables quant au respect des engagements pris lors de la ratification des conventions internationales du travail[40].

Les circonstances actuelles sont trop proches des conditions qui existaient lorsque la Société des Nations et l’OIT ont été créées. Nous assistons à une recrudescence atroce de la violence, qui nous éloigne de la paix durable avec la justice sociale dont ont rêvé les membres de la Commission de la législation internationale du travail en 1919.

Si discuter de “l’avenir du travail” est intéressant, les questions en suspens depuis 1919 ne sont toujours pas résolues.

Remerciements

En premier lieu, je voudrais remercier Hug Palou i Miquel, le Directeur de l’Archive municipal d’Arenys de Mar de m’avoir fourni des informations sur Rafael Martínez Ortíz et la construction du mausolée. Il m’a aussi indiqué que je ne devais pas confondre le nom officiel du cimetière municipal d’Arenys avec le mot « Sinera » utilisé dans le recueil de poésies « Cementiri de Sinera ». En effet, le poète catalan Salvador Espriu, dans le recueil mentionné, a utilisé, en sens inverse, les lettres qui composent le nom de la ville d’Arenys.

Je tiens à exprimer ma profonde gratitude à Pierre Sayour d’avoir établi la version française de mon texte. Pierre a été un de rares collègues du département des normes internationales du travail qui m’a toujours frappé par sa modestie. Pierre est un grand syndicaliste avec lequel j’ai été, quelquefois, en total désaccord.

Pour ne pas froisser la proverbiale modestie de Pierre, je voudrais terminer par le récit d’une histoire qui concerne Cuba, la mère de Pierre et mon travail au Bureau : Madame Sayour occupait un poste stratégique quand j’ai fait mes premiers pas, en tant que stagiaire, au département, entre septembre 1986 et mars 1987. Pendant mon stage, j’avais continué à travailler comme consultant pour le Secrétariat économique de l’Amérique latine, le SELA, et j’avais été invité, au nom du SELA, à participer à une réunion ministérielle du Groupe des 77 prévue à La Havane, en vue d’une conférence de la CNUCED. Un vol charter de la compagnie aérienne cubaine allait amener le personnel de la CNUCED et autres dignitaires qui devaient assister à la conférence.

Je voulais donc interrompre mon stage au BIT, ce qui n’était pas du tout du gout de celui qui avait manœuvré pour me donner l’opportunité d’avoir un vrai travail, mon très cher ami Héctor Bartolomei de la Cruz. Héctor n’avait pas eu des difficultés à comprendre que je voulais partir sous les cocotiers et abandonner le travail au département à ce moment crucial de la relecture, après la réunion de la commission d’experts que Héctor avait, à l’époque, la haute responsabilité de coordonner.

Je devais donc contrarier Héctor et obtenir l’aval de quelqu’un de plus haut placé, Monsieur Dao, le chef de service. Pour appuyer ma démarche, devant moi, Madame Sayour a interpellé à M. Dao, le chef de service, en lui disant qu’il ne pouvait pas me retenir si j’avais un engagement (payé) ailleurs.

Et je suis parti à Cuba, où j’ai logé au Hilton, fumé un cigare, donné la main à Fidel, mangé des langoustes, visité la Bodeguita del Medio et autres endroits mythiques.

Malgré mon escapade cubaine, le département a accepté de me reprendre pour le reste de ma vie professionnelle.

Avant de conclure, je voudrais aussi remercier Germán López Morales qui pense que j’avais été trop modeste de dire que le seul succès que j’ai eu dans ma carrière avait été de corriger le nom du délégué cubain dans la photo de la Commission de la législation internationale du travail. Prenant un café à La Biela, à quelques pas de la tombe du Comte Zolotowksi, Mario Ackerman s’est souvenu de l’énergie que j’avais mise pour obtenir que la commission d’experts se prononce sur le besoin de protéger les travailleurs en cas de licenciement injustifié. Je crois que d’autres collègues auraient pu défendre, avec le même succès, le besoin de garder le dogme du plein emploi, productif et librement choisi ou de s’assurer de l’efficacité des consultations tripartites en matière de normes internationales du travail.

Pour clore ce récit, je voudrais convoquer une dernière fois l’esprit qui a régné au moment de la photo prise en 1919 et le souvenir de quelques collègues et de ma famille qui ont tellement contribué au fait que le travail au Bureau ait été particulièrement agréable.

[1] Burgos, A., Contrastes europeos y orientación americana, Roma, Tipografía Failli, 1925.

[2] www.eltonodevoz.com La photo du docteur Martínez Ortíz accompagne l’article de Jorge Ferrer intitulé “Primera transición…”, publié le 16 juillet 2007/16 août 2010.

[3] BIT, Commission de la législation internationale du Travail. Bulletin officiel, vol. I, (Genève), pp. 1-260 – Disponible en :

http://www.ilo.org/legacy/french/lib/century/sources/sources1919.htm

[4] En 2017, sous le titre Retour à Lemberg, Philippe Sands a publié un livre magistral : East West Street. On the Origins of “Genocide” and “Crimes against Humanity”, 2016. Voir plus loin une autre reference à l’ouvrage de Ph. Sands, note 32.

[5] “On January 23 [1919], the government of Czechoslovakia, capitalizing on Poland’s distraction, sent troops across the demarcation line established on November 5, 1918, by the two national councils, a frontier that largely conformed to the province’s ethnic composition. […] The next day, January 24, 1919, the Great Powers issued a “solemn warning” against further coups de main. Echoing their earlier empty admonitions to Romania and to Poland, the council proclaimed its collective moral and political authority over the entire region of Eastern Europe”. Fink, Carole. Defending the Rights of Others. The Great Powers, the Jews, and International Minority Protection, 1878-1939, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 142-143.

[6] Informations sur la page Wikipedia relatives à Samuel Gompers.

[7] Di Palma Castiglione, G. E., Italian Immigration into the United States 1901-4, The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 11, No. 2, Sep. 1905. Disponible sur: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2762660?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[8] Nouvelle Anthologie, 16 août 1928, fascicule 1354, pages 504-517

[9] Gramsci, A. Quaderni del Carcere, cuaderno II, párrafo 84.

[10] Eduardo Zamacois est né à Cuba en 1873 et est mort à Buenos Aires en 1971. Romancier et journaliste bien connu en son temps, ses œuvres sont complètement tombées dans l’oubli.

[11] Cuba pendant les années de la Première Guerre mondiale,

http://www.elgrancapitan.org/portal/index.php/articulos3/historiamilitar/569-cuba-en-los-anos-de-la-1-guerra-mundial

[12] “Les États-Unis ont organisé l’achat mondial des récoltes cubaines et les prix ont été déterminés par leurs mécanismes de contrôle pour la guerre, de sorte qu’en 1917-1918 a été payé à 4,60 cents la livre et en 1918-1919 à 5,50 cents la livre. C’était la principale contribution que Cuba apportait aux alliés de la guerre mondiale. D’autre part, durant cette période des capitaux américains se sont portées massivement sur Cuba, au point où l’île est devenue le premier bénéficiaire des investissements américains sur le continent. Lopez Civeira, F., El dulce cubano en la Primera Guerra Mundial, 6 août 2104, http://www.trabajadores.cu/20140806/eldulce-cubano-en-la-primera-guerra-mundial/

[13] Burgos, A., Contrastes europeos y orientación americana, Rome, 1925, pages 117-118.

[14] Burgos, A., ibíd., pages 118-119.

[15] Fernando Ortiz (La Havane, 1881-1969). La Fondation Fernando Ortiz de La Havane (http://www.fundacionfernandoortiz.org/index.php) offre les informations suivantes : F. Ortiz commence ses études de droit à l’Université de La Havane et obtient un baccalauréat de l’Université de Barcelone en 1900 et un doctorat à Madrid en 1901. En 1902-1905, il travaille au service consulaire cubain en Italie et suit les cours de criminologie de Cesare Lombroso et Enrique Ferri. Avec un prologue de Cesare Lombroso, F. Ortiz publie Hampa Afro-cubana. Los negros brujos. Apuntes de etnografía criminal, 1906. Pendant une décennie (1917-1927), F. Ortiz a été élu à la Chambre comme représentant du Parti libéral. F. Ortiz est considéré comme “le précurseur des études sur la culture africaine à Cuba… dans son ouvrage fondateur, le Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azúcar [1940] introduit le concept de transculturation, considéré par Bronislaw Maniloswski comme une de ses plus grandes contributions à l’anthropologie culturelle”. Aux États-Unis, un livre a été publié en son honneur : Cuban Counterpoints : The Legacy of Fernando Ortiz, sous la direction de Mauricio A. Font et Alfonso W. Quiroz. Lexington Books, 2005.

[16] Cuba en la Paz de Versalles. Discurso pronunciado en la Cámara de Representantes en la sesión del 4 de febrero de 1920 por Fernando Ortiz, Vicepresidente de la Cámara por el Partido Liberal. La Universal, 1920. Publication cataloguée à la Library of Congress, qui ne figure pas dans la liste des publications de la Fondation Fernando Ortiz.

[17] Le principe dirigeant selon lequel “le travail ne doit pas être considéré simplement comme une marchandise ou un article de commerce” a été adopté par la Commission de la législation internationale du travail lors de sa réunion du 11 mars 1919 à Paris, à l’unanimité, par 11 voix pour tous ses membres. Ce texte a été incorporé à l’article 427 du Traité de Versailles. La Déclaration de Philadelphie (mai 1944), qui a été incorporée dans la Constitution de l’OIT, simplifie l’expression de 1919 et dit : “Le travail n’est pas une marchandise”.

[18] Cosme de la Torriente prononça deux discours pour souligner l’importance du vote en faveur de Don Antonio et les difficultés diplomatiques surmontées pour obtenir son élection, en mars 1922, à l’occasion de la cinquième conférence annuelle de la Société cubaine de droit international. James Brown Scott (États-Unis), Alejandro Álvarez Jofré (Chili) et Luis Anderson Morúa (Costa Rica) étaient présents. Cosme de la Torriente, ‘Bustamante and the Permanent Court of International Justice and Cuba’ et ‘The United States of America and the League of Nations’, International Conciliation, septembre 1922.

[19] C. Wilfred Jenks (1909-1973) a été le sixième Directeur général de l’OIT. Voir la biographie très détaillée : Jaci L. Eisenberg, ‘Jenks, Clarence Wilfred’ in IO BIO, Biographical Dictionary of Secretaries General of International Organizations, Edited by Bob Reinalda, Kent J. Kille and Jaci Eisenberg,

http://www.ru.nl/fm/iobio.

[20] The Contemporary Review, February 1931, pages 209-218.

[21] Ibíd., p. 211.

[22] Alejandro Álvarez Jofré (1868, Santiago du Chili – 1960, Paris) a réussi à être juge à la Cour internationale de Justice de 1946 à 1955 en écrivant ” les fameux Avis dissidents d’une des affaires sur le Sahara occidental, cité par Henkin et Schachter comme base du droit international du développement. Il a écrit d’innombrables ouvrages sur le droit international public “, selon Wikipédia. Voir également la référence à Álvarez Jofré à la note 18.

[23] A la Cour permanente, seuls deux juges brésiliens ont siégé : Ruy Barbosa de Olivera (1922-1923), puis Epitacio da Silva Pessôa (1924-1930). Information tirée d’une publication du Secrétariat de la Cour internationale de Justice : La Cour permanente de Justice internationale, La Haye, 2012, p. 206.

[24] José Gustavo Guerrero (San Salvador, 1876 – Nice, 1958) a étudié à l’Université d’El Salvador, où il s’est distingué par son activité politique militante contre le général Rafael Antonio Gutiérrez, président de son pays. Il a dû poursuivre ses études de droit à l’Université nationale du Guatemala, où il a obtenu son diplôme en 1898. Cette année-là, M. Guerrero retourne à son pays où il entreprend une activité politique qui l’amène à devenir ministre des Affaires étrangères (1927-1928) et à présider l’Assemblée de la Société des Nations de 1929 à 1930. M. Guerrero a été magistrat et président de la Cour internationale permanente de Justice jusqu’à sa dissolution en 1946. M. Guerrero a été nommé à la Cour internationale de Justice et en a été le premier président (1946-1949).

[25] Francisco José Urrutia Ollano (Popayán, 1870 – Bogotá, 1950), juriste, homme politique et diplomate colombien. Après avoir été ministre des Affaires étrangères (1908-1909, 1912-1914), il a représenté la Colombie devant la Société des Nations et l’OIT. En 1931, il préside le Conseil de la Société des Nations et obtient sa nomination comme juge à la Cour permanente (1932-1942).

[26] Julio López Oliván (1891-1964) diplomate espagnol, en poste à l’Ambassade de la République espagnole à Londres, il aurait soutiré des fonds de la République en faveur de l’achat d’armes pour les rebelles. Quand Pablo de Azcárate est nommé par la République à Londres, López Oliván s’installe à La Haye où il devient Greffier de la Cour Permanente (octobre 1936-1946). López Oliván a été nommé Greffier de la Cour internationale entre 1953 y 1960. Sur Pablo de Azcárate voir notas 35-39.

[27] Les ratifications suivantes ont été enregistrées le 7 juillet 1928 : convention n° 13 (céruse (peinture)), convention n° 16 (examen médical des mineurs (travail maritime)), convention n° 22 (contrat d’engagement des gens de mer), convention n° 23 (rapatriement des gens de mer).

[28] Les ratifications suivantes ont été enregistrées le 6 août 1928 : Convention no 3 (protection de la maternité), Convention no 4 (travail de nuit (femmes)), Convention no 5 (âge minimum (industrie)), Convention no 6 (âge minimum (mineurs)), Convention no 7 (âge minimum) (travail maritime)), Convention no 3 (protection de la maternité), Convention no 4 (travail de nuit (femmes), Convention no 5 (âge minimum), Convention no 6 (âge minimum) (industrie) et convention no 7 (âge minimum)) 8 (indemnisation du chômage (naufrage)), convention n° 17 (indemnisation des accidents du travail), convention n° 18 (maladies professionnelles), convention n° 19 (égalité de traitement (accidents du travail)), convention n° 20 (travail de nuit (boulangerie)).

[29] Maison d’édition “Le livre libre” 141, Boulevard Péreire, Paris, 1929. La version numérique des deux volumes peut être consultée à la Biblioteca Digital Hispánica : http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000015405n

[30] Rafael Montoro (1852-1933), fondateur et idéologue du Parti libéral autonome, auquel appartenait également Martínez Ortíz. Rafael Montoro a été secrétaire d’État sous la présidence du général Machado, tout comme Martínez Ortiz.

[31] Tomás Estrada Palma (1835-1908) fut le premier président élu de Cuba (1902-1906).

[32] Selon El Mundo, le Dr Martínez Ortiz mourut à Fontainebleau en 1932. A la mairie de Fontainebleau, on m’a dit qu’il n’y avait pas de tombe au cimetière municipal au nom de Rafael Martínez Ortiz.

[33] Ph. Sands, Retour à Lemberg, op. cit., page 110.

[34] Alfred Zimmern, Paper on the League of Nations, FO 371/4353 (PC 29/29), cite par C. Fink, Defending the Rights of Others, op. cit., page 154 note 136.

[35] J. Headlam-Moreley, Memorandum on the Right of Appeal of Minorities to the League of Nations, 16.V. 1919, in A memoir of the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, Londres, 1972, pp. 108-109, cité et traduit de l’anglais vers l’espagnol par Xosé M., “A memoir of the Paris Peace Conference”, 1919, Londres, 1972, pp. 108-109. Núñez Seixas, La cuestión de las minorías nacionales en Europa y la Sociedad de las Naciones (1919-1939) : el contexto histórico de la actuación de Pablo de Azcárate, in Pablo de Azcárate, Minorías Nacionales y Derechos Humanos, Congreso de los Diputados, 1998, page 67.

[36] Xosé M. Núñez Seixas, Nacionalismo y política exterior: España y la política de minorías de la Sociedad de las Naciones (1919-1936), Hispania (Madrid), 55:189 (1995: enero/abril).

[37] La Commission des affaires étrangères du Congrès des députés et de l’Université Carlos III de Madrid ont publié un livre en l’honneur de Pablo de Azcárate, Minorías Nacionales y Derechos Humanos, Madrid, 1998. L’œuvre comprend une contribution de son fils Manuel Azcárate, l’étude précitée de Núñez Seixas et la traduction espagnole d’une monographie de Pablo de Azcárate publiée en anglais.

[38] Pablo de Azcárate a démissionné de son poste à la Société des Nations et a accepté la représentation diplomatique de la République espagnole, d’abord à Paris puis à Londres. A Londres, Pablo de Azcárate a remplacé Julio López Olivan. Sur Julio López Olivan, voir note 26.

[39] Nuñez Seixas, Nacionalismo y política exterior, op. cit., note 90.

[40] https://natanelkin.wordpress.com/2018/06/13/matanza-de-dirigentes-indigenas-de-saweto-sin-condenar-la-oitdeja-prosperar-la-impunidad/

Traduction en français par Pierre Sayour